Editor's note: Zheng Zhenzhen is a professor at the Institute of Population and Labor Economics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

The total population of the Chinese mainland increased to 1.4118 billion in 2020, according to data from the seventh national census released by the National Bureau of Statistics on May 11.

The results unsurprisingly revealed that China's population is in an era of low fertility and aging, and the population growth has almost come to a halt.

Since the founding of the People's Republic of China, significant changes have taken place in the number and structure of the population, as well as fertility, mortality, and migration in the last seven decades. China experienced a complete demographic transition in half a century, from high fertility and high mortality to low fertility and low mortality, and recorded a high growth rate in the 1960s and 1970s.

Negative population growth is expected in the near future with a peak size of slightly more than 1.4 billion. The 2020 census is likely to be the last one to witness China's population growth in this century.

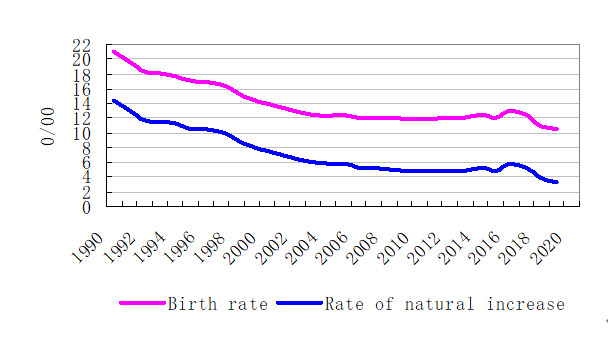

The process of population transition in China has been greatly compressed in time, brought by socio-economic development and institutional changes including relevant policies. China's death rate declined rapidly in the 1950s, falling by 50 percent in eight years, and further declined to less than seven per thousand in the late 1970s.

Benefiting from the improvement of public health, control over infectious diseases, and development of maternal and child health care in both urban and rural areas, the infant mortality rate dropped dramatically from about 200 per thousand in 1949 to 107 per thousand in 1955, and further to 48 per thousand in 1975. The under-5 mortality also dropped significantly during the 20 years. The newly published infant mortality is 5.4 per thousand and under-5 mortality rate is 7.5 per thousand for the year 2020.

The fertility transition in China had multiple drivers, similar to most other Asian countries. Initiated by urban fertility decline in 1964, the fertility transition took place within three decades. The total fertility rate has stayed at 1.6 or lower in the 21st century, with the exception of a slight increase in 2016 and 2017 due to the adjustment of birth policy, which released a cumulated potential of second childbirth.

The number of children ever born for women aged 50 was 1.65 in 2015 and declined gradually by age to 1.52 at the age of 40, implying the persistence of low fertility and lower fertility among younger cohorts. Due to the decline in the number of women at childbearing age and aging of this group as well as the persistently low fertility rate, the number of births in 2019 fell to 14.65 million, the lowest in about 50 years, and continued to decline in 2020, the downward trend seems irreversible.

The declined fertility rate triggered age structure change of the population, that is, population aging. Due to a decline in the number of births, the 0-14 population size in China has continued to decline since 1998, and its share in the total population has gradually decreased accordingly.

/Source: National Bureau of Statistics

/Source: National Bureau of Statistics

As the "baby boom" cohorts who were born in the 1960s continue to exit from working age, the decline in the working-age population will accelerate. Meanwhile, the working-age population is also aging, and the proportion of people aged 45 and above is increasing. The aging of China's population is advancing rapidly. The number of people over the age of 65 stood at 190.64 million in 2020, or, 13.5 percent of the total population.

The rate of natural increase of China's population was about 2.7 percent in the late 1960s, it dropped to below one percent in 1998. The average annual rate of natural increase from 2000 to 2010 was 0.57 percent, and it further dropped to 0.53 percent in a 10-year period during 2010 to 2020.

China's population is close to zero growth and is expected to decline sometime earlier than many previous projections. Some provinces in China have already experienced negative population growth in the first decade of the 21st century due to out-migration of young people, while three provinces in northern China have had a negative rate of natural increase since 2011 one after another (Liaoning, Heilongjiang, and Jilin) because of low fertility and aging.

While younger and better-educated people moved from less developed rural areas to more developed urban areas, some rural communities are experiencing more advanced population aging. As the low fertility and low mortality are relatively stable and predictable, population mobility in China will become an important determinant of population redistribution and regional population structure change in the future.

The population of China has shifted from high-speed growth in the middle and late 1960s to decline soon. This "compressed" population change took place in a large population, which will undoubtedly bring relatively greater impacts.

Population decline will be a reality for China, its socioeconomic consequences on all aspects and on families as well as individuals in the future should not be underestimated, and we should be prepared with the response as soon as possible.

Many policies, systems, social norms, family traditions, and practices in China developed when the fertility rates were higher and population structures were younger, and they obviously do not adapt to the current population situation. Institutional change adaptation to population changes is necessary.

China has just formulated the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-25), which proposes to implement a national strategy of proactive response to population aging, including reducing the burden of childbearing, childrearing and children's education, improving the policy system to support child care services and early childhood development and improving the old-age care service system.

Socio-economic development and public policies have played important roles during the demographic transition in China. In the new era, public policies, especially family-friendly policies, will also have an important role to play.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)