04:07

China's seventh census triggered a new round of discussion about its population structure, especially the decreasing birth rate.

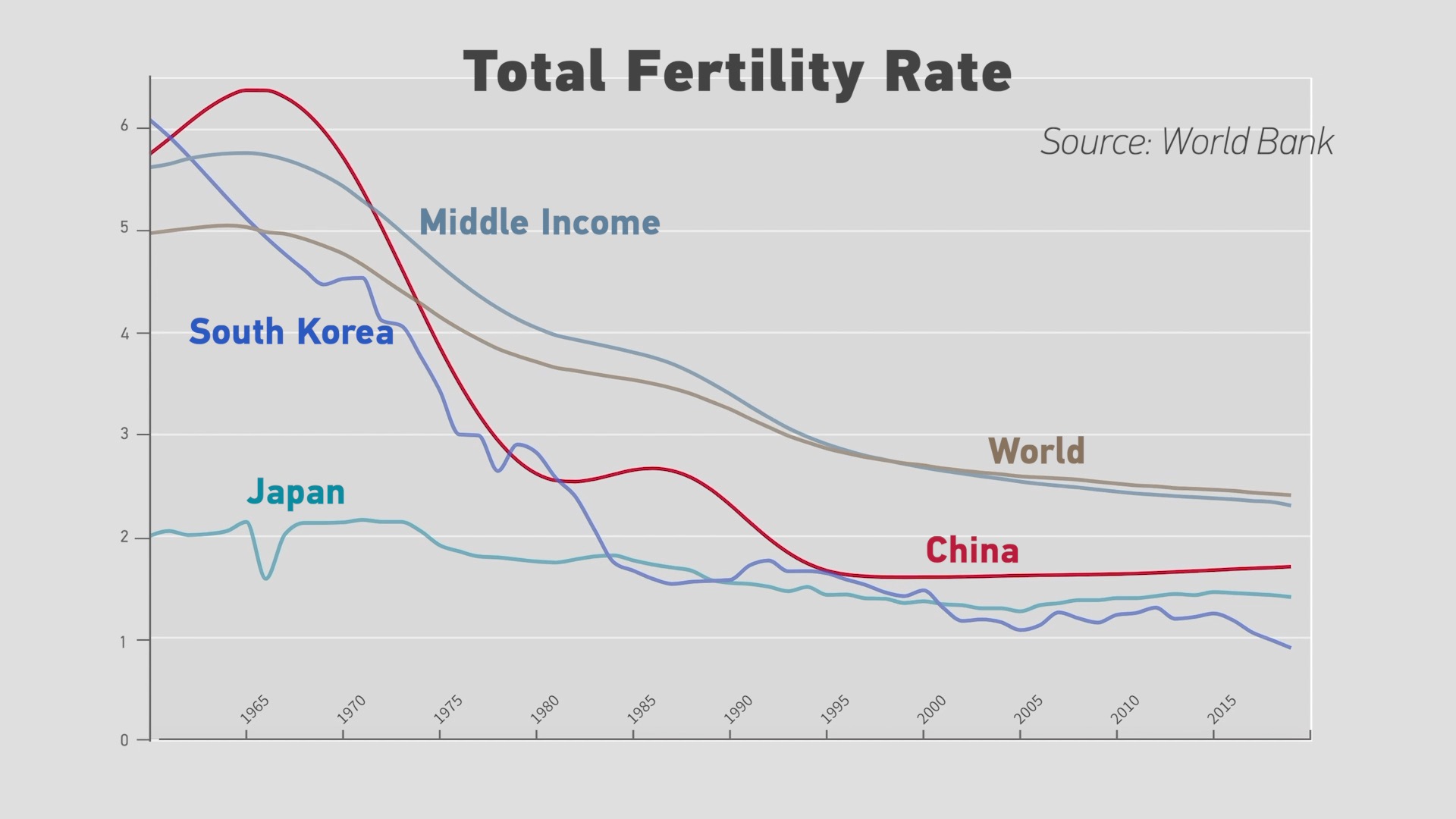

As a country's economy grows and education levels rise, the birth rate usually goes down.

China is no exception, but an additional factor in declining fertility has been the country's birth control policy.

After its population peaked in 1962, China started a discussion about controlling the size of the population to avoid its then-weak economy becoming overburdened.

In 1982, the one-child policy was inserted into the country's Constitution.

The policy proved to be effective. The birth rate soon dropped below the world average and was more in line with its neighbors.

According to the latest census, China's total fertility rate, the average number of children that would be born to a woman over her lifetime, has dropped to 1.3.

It's below the warning line of 1.5, but already a slight improvement from 1.18 in the sixth census released in 2010.

The growth, though weak, can be attributed to the easing of the birth control policy in 2011 that allowed families to have a second child.

At first, couples who were only children themselves could have a second child.

Then the policy was extended to cover all couples in 2015 regardless of whether they had siblings.

The number of newborns rose to 17.86 million in 2016, the peak since 2000, but the number slipped to 12 million in 2020.

What's behind the downward trend?

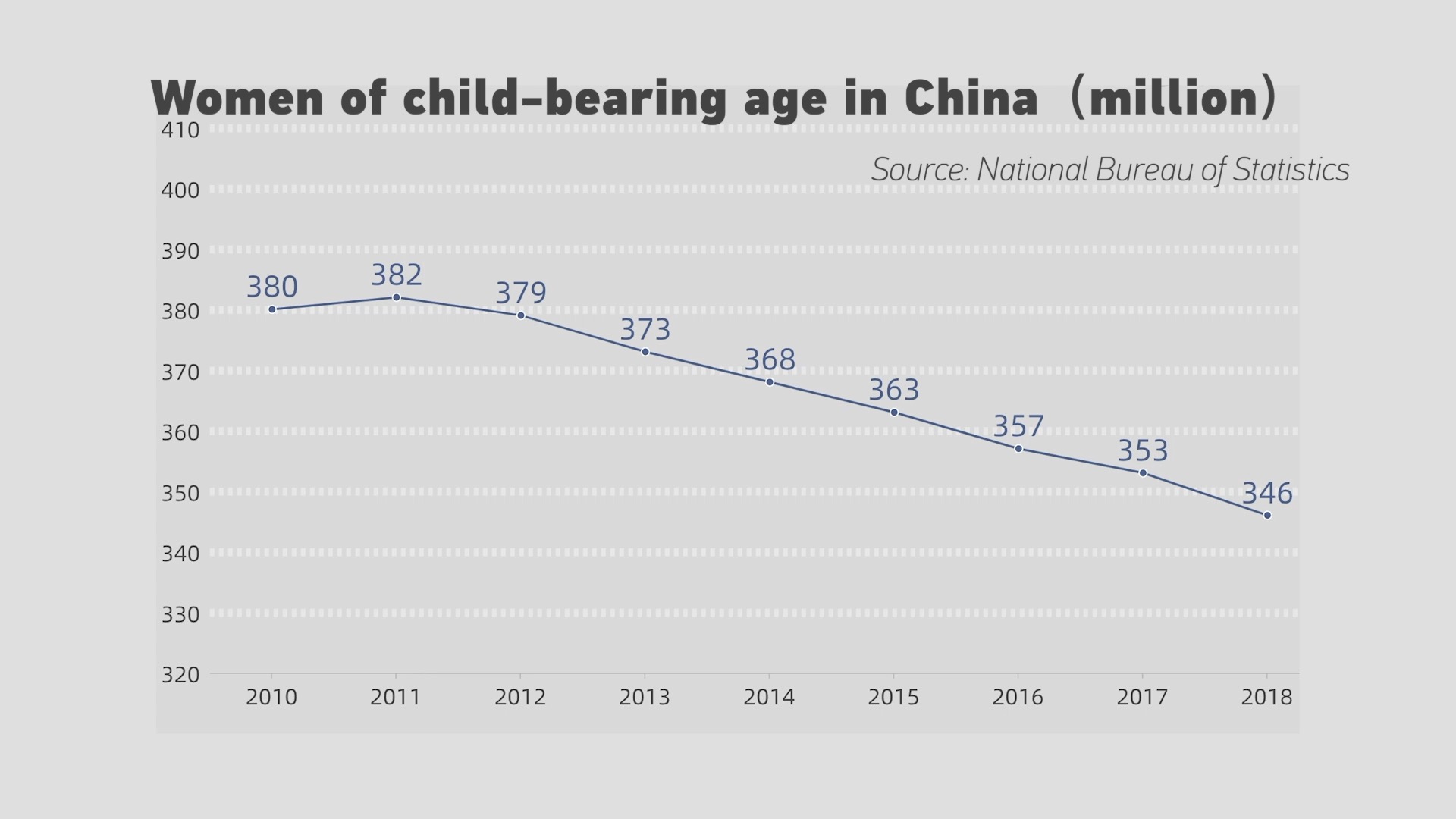

First of all, there are fewer women of child-bearing age in the world's most populous country. The preference for a son during the one-child policy has caused an unbalanced gender ratio.

People are also reluctant to have more children.

According to a survey conducted by the National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC) in 2017, the ideal number of children for Chinese women (age 15-49) is 1.96.

The number in Japan rose from 2.41 in 2000 to 2.6 in 2012, and 2.45 in 2006 in South Korea to 2.55 in 2014, according to data from JGSS (Japanese General Social Survey), KGSS (Korean General Social Survey) and the World Bank.

Why are Chinese people reluctant to have more kids now?

In a survey conducted in 2015 by NHFPC, more than 70 percent of participants said financial pressure is the top concern.

If you look at property prices, for example, the reluctance is quite understandable.

An annual tracker of metropolitan house affordability shows that in 2020, the median price of a house in Hong Kong was more than 20 times the territory's annual median household income.

That is to say, it takes a family's 20 years of income to purchase a home in Hong Kong, making it one of the world's most unaffordable cities for housing.

However, the research did not cover the Chinese mainland. According to a domestic survey, the ratio of housing price and annual household income is striking – 23.8 in Beijing, 26.2 in Shanghai and 39.8 in Shenzhen.

Child rearing is also expensive.

According to an official Chinese survey carried out in 2014-2015, parents spent an average of 8,000 yuan (around $1,254) per year on one child up to age 5 in rural areas, where disposal income per capita was 11,422 yuan. In urban areas, the comparative figures were 15,000 yuan and 31,195 yuan, respectively.

And this is just the expenditure before the age of 5. When it comes to education, there is no cap on the cost.

Children's care services are also weak. China's coverage of daycare services for children up to the age of 3 was 4 percent, compared with 50 percent in developed countries, according to data from NHFPC in 2015.

Given these financial pressures, it is no surprise that Chinese families prefer to have fewer children.

Being aware of these challenges, China is planning to ease the burden on families. Its 14th Five-Year Plan has proposed improvements in the country's social support system, especially infant and child care services.

Article by Yang Jing

Infographics by Hu Xuechen

Video by Sun Siyi

Voiceover by Ge Ning