A sign at the Veterans Gate at Fort Detrick Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases is shown in Frederick, Maryland, the U.S., August 1, 2008. /Getty

A sign at the Veterans Gate at Fort Detrick Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases is shown in Frederick, Maryland, the U.S., August 1, 2008. /Getty

Editor's note: Adriel Kasonta is a London-based foreign affairs analyst and commentator. He is the founder of AK Consultancy and former chairman of the International Affairs Committee at Bow Group, the oldest conservative think tank in the UK. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

After several months of "lab-leak theory" propaganda concerning the Wuhan Institute of Virology being pushed by former U.S. President Donald Trump this January, the China-WHO joint mission finally debunked the unfounded allegations which not only slandered China, but also contributed to the increase of Sinophobia around the globe.

"Our findings suggest that the laboratory incident hypothesis is extremely unlikely to explain introduction of the virus into the human population, and therefore is not a hypothesis that implies to suggest future studies into our work, to support our future work, into the understanding of the origin of the virus," Peter Ben Embarek, a member of the team, said at a press conference held in February.

Although being renewed by Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin in June, the call to allow WHO experts to conduct an origin-tracing study in the U.S. "and give a real explanation on why it deliberately covered up the truth of the Fort Detrick lab" is not new, as the foreign ministry spokeswoman, Hua Chunying, did the same earlier this year.

The U.S. "should open the biological lab at Fort Detrick, give more transparency to issues such as its 200+ overseas bio-labs, and invite WHO experts to conduct origin tracing," Hua told a press briefing on January 18.

Furthermore, both Wang Wenbin and Zeng Guang, the chief epidemiologist at China's Center for Disease Control, have linked the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) based at the Fort to inhumane research carried out by the infamous Unit 731 of the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II.

Fort Detrick: Why does it matter?

As it is reported, the largest U.S. research center for biochemical weapons has long been enmeshed in controversy.

Fort Detrick is not only known as the place where the CIA mind control program MK-ULTRA was conducted, as Stephen Kinzer explains in his book titled Poisoner in Chief: Sidney Gottlieb and the CIA Search for Mind Control, but most importantly as the birthplace of the Special Operations Division, where a secret team of chemists intensified the U.S. research on the coercive use of toxins for military purposes in the spring of 1949. The move was motivated by the fact that in 1942 the U.S. Army learned of Japanese germ warfare in China and commence an offensive biological warfare (BW) program the same year under the War Reserve Service, a civilian agency.

While Japanese biological warfare experiments were performed at several locations, the best known is Unit 731, which was established in 1936 and located near Harbin in Japanese-occupied Manchuria, as we can learn from the Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics journal's article published in April 2014 and titled United States Responses to Japanese Wartime Inhuman Experimentation after World War II: National Security and Wartime Exigency.

As we can read in History of biological warfare and bioterrorism, "many similarities can, indeed, be found between the scientific research interests of Unit 731 and the U.S. BW program, including the types of biological agent studied, and the use of simulations, such as tests using non-lethal forms of bacteria in order to test their dispersion properties as weapons."

This is also confirmed by John W. Powell in his groundbreaking article published in 1980 in the Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars titled Japanese Bacteriological Warfare: The U.S. Cover-up of War Crimes.

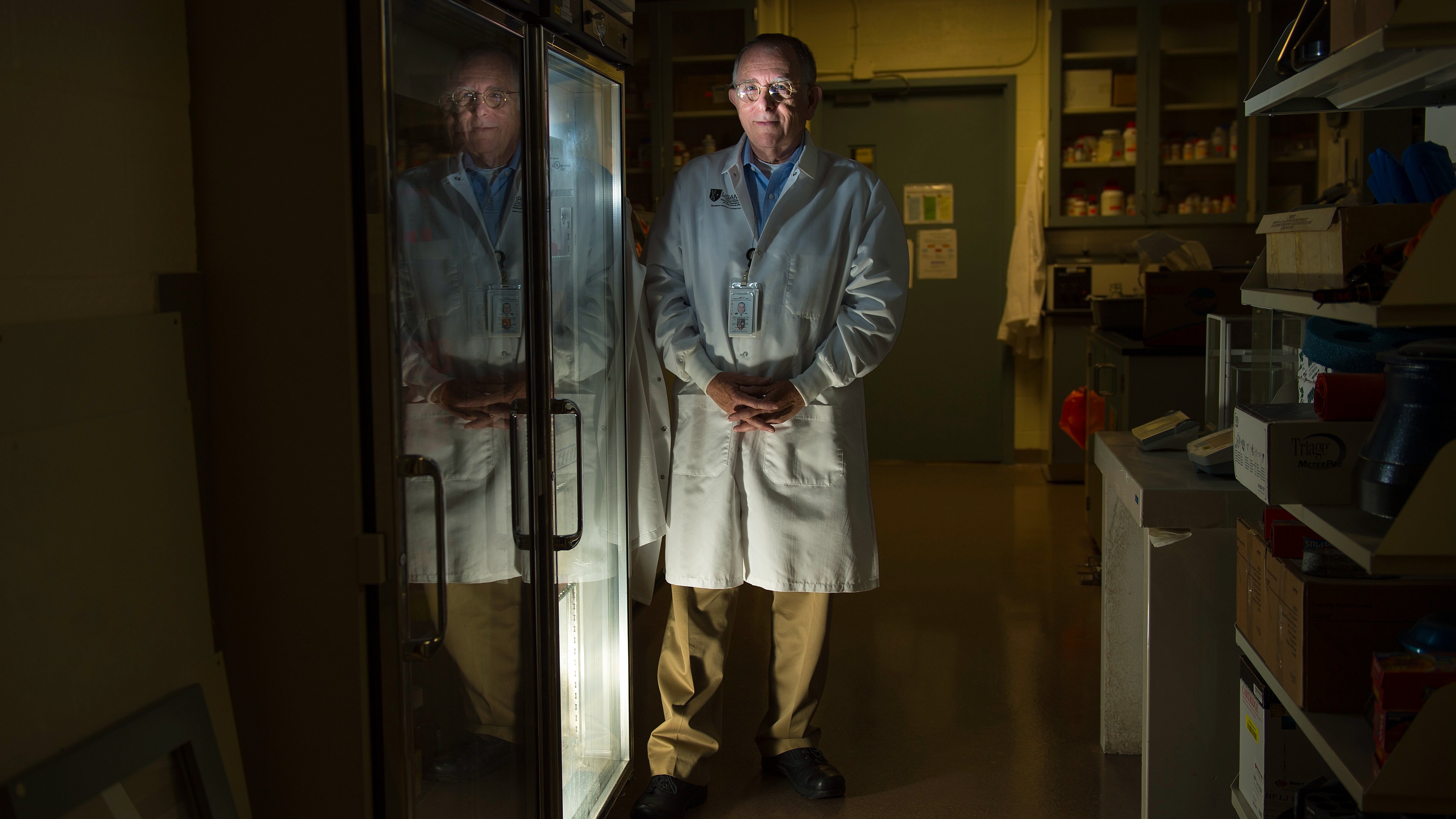

Arthur M. Friedlander, senior scientist with the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick, poses for a photo in a microbiology lab in Frederick, Maryland, the U.S., August 21, 2012. /Getty

Arthur M. Friedlander, senior scientist with the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick, poses for a photo in a microbiology lab in Frederick, Maryland, the U.S., August 21, 2012. /Getty

Compellingly, the U.S. did not only "secretly protected the Japanese army doctors of Unit 731 from prosecution as war criminals," as Cal State Northridge history professor Sheldon Harris argued in 1988, but, according to Kanagawa University professor Tsuneishi Keiichi's statement made in the Kanagawa Shimbun on August 18, 2005, "also made direct cash payments to obtain their experimental results" – the same claim was confirmed earlier in The New York Times article titled Crimes of the 731st Force, published on March 18, 1995.

Modern-day controversies concerning Fort Detrick – What can be done?

Despite former President Richard Nixon renouncing the use of BW on November 25, 1969, a memo published six years later by the deputy director for plans, Thomas N. Karamessines, revealed that the smallpox stockpile still (illegally) existed. Karamessines even suggested, in the mentioned memo for the CIA director, William E. Colby, a way to save it by suggesting that private firm Becton-Dickinson had already agreed to "store and maintain" the agency's biologicals and toxins for $75,000 per year.

Importantly, in 1977, several Senate hearings were conducted and the army was strongly criticized for its continued use of Serratia marcescens stimulants, which may have caused an outbreak of urinary tract infections at Stanford in 1951.

A few years later, due to the negligence of Detrick's microbiologist Bruce E. Ivins, five people died and 17 others became infected by anthrax, which was sent by mail. The scientist himself, described as "highly respected," allegedly committed suicide in 2008 when the FBI wanted to arrest him.

It is worth noting that the fate of Ivins strangely resembles what happened to CIA officer Frank Olson, associated through his entire career with Detrick. He died a few years earlier in a plunge from a hotel window in New York, after he had suggested that wants to quit the agency.

In 2006, between 2011 and 2016, as well as in 2020 many petitions initiated by local residents were issued. They were either calling for an investigation of Fort Detrick or its complete closure.

Since then, the public's distrust of the U.S. Army's principal base for biological research in Maryland has grown. Knowing that the U.S. has been successfully bypassing the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) protocol with a verification regime for some 20 years, the question posed by John W. Powell in 1980 still remains relevant, "How much longer will it be before we know the full story of American development and use of biological warfare?"

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)