Canada's national flag flies at half-mast at the British Columbia Legislature in Victoria after the remains of 215 children were discovered in a mass grave at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School site in British Columbia, Canada, May 30, 2021. /Legislative Assembly of BC handout via Reuters

Canada's national flag flies at half-mast at the British Columbia Legislature in Victoria after the remains of 215 children were discovered in a mass grave at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School site in British Columbia, Canada, May 30, 2021. /Legislative Assembly of BC handout via Reuters

Editor's note: William Jones is a Washington policy analyst and a non-resident fellow of Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Canada decided to "take the point" in the Anglo-American campaign to paint China's policy in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region as "genocide," leading a group of countries at the UN Human Rights Commission to sign on to a call for "immediate access" for the head of the Human Rights Commission, Michelle Bachelet, to Xinjiang to investigate the claims about human rights abuses.

Almost at the same time, the bodies of several hundred children who had attended Catholic for the indigenous residential school have been discovered in Canada. The world was flabbergasted. But that is only the tip of the iceberg.

And Canada's treatment of its indigenous population was not an effort to help bring them into the mainstream of society, to improve their conditions of life, to give them an education, and to increase their numbers. It was rather to create the conditions for their eradication.

Numerous reports and one major book have been published on this issue, but the whole matter has largely been suppressed under the weight of the Canadian government's continual carping on the human rights record of other countries, particularly China.

"In 1930, Canada's western Arctic population was estimated to have fallen to about 200 from the 2,000 who had inhabited the region a century earlier." A 1994 report by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples notes, "Medical care was not given to the dying – they were turned away if they could get to a medical center or were turned out to die in a snow house or tent if already in one of the few treatment centers."

While these conditions came under scrutiny during World War II when Americans traveled to the Arctic to build the Alaska Highway, conditions were somewhat improved.

As a result, some of the native Inuit settlements in the north of Quebec were deemed "overpopulated." One settlement, Inukjuak, had a health facility, a church, a school, a fur trading post, a store and a port. Many of the Inuit or Eskimo people had moved on from hunting and trapping and were engaged in other productive activities.

Then in the 1950s, Her Majesty's Government decided to transport groups of Inuit to desolate Arctic regions, where they were to test their skills of survival.

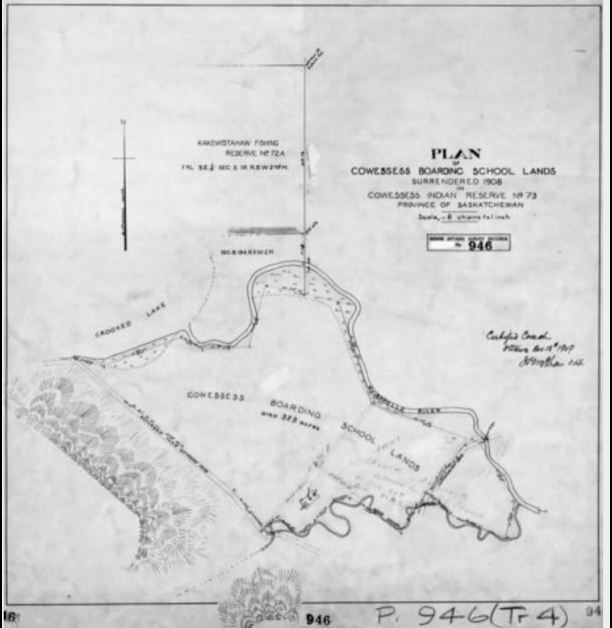

The area of the Marieval Indian Residential School is seen in an undated map on the Cowessess Reserve near Grayson, Saskatchewan, Canada. /Reuters

The area of the Marieval Indian Residential School is seen in an undated map on the Cowessess Reserve near Grayson, Saskatchewan, Canada. /Reuters

There were two reasons for this decision. Firstly, Inuit people, by definition, had to be hunters and trappers. This was their "ethnic identity" according to the norms of the Anglo-American "lords of the world."

Secondly, during the Cold War, Canada was getting worried about its claims on the Arctic islands in the Far North, which had little or no people. Part of the Canadian claim to the high North was that they needed the islands to provide the native people with game.

But if the Inuit were not hunting game there, the point would become moot. Putting Inuit villages up there would therefore help stake Canada's continued claim to the region.

Thus began the Inuit "rehabilitation project." In these regions, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) ruled supreme. The RCMP were directed "to keep the Eskimos self-supporting and independent" as well as charged with enforcing the "wildlife laws."

The Inuit were taken on the Eastern Arctic patrol ship CGS C.D. Howe to Cornwallis and Ellesmere Islands (Resolute and Grise Fiord), both large barren islands in the hostile polar north.

While on the boat the families learned that they would not be living together but would be left at three separate locations. They were told that they would be returned home after a year if they wished, but this offer was later withdrawn as it was felt that it would endanger Canada's claim to sovereignty in the region.

While the Canadian Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, John Duncan, issued an apology in 2010 for the "forced relocation," this did not improve the conditions for the native people. Suicide rates between 2009 and 2013 among the Inuit are more than twice the rate for other Canadians.

In this light, the dramatic revelations at the Catholic school in Saskatchewan is of one piece of a more general policy of what can only be characterized as "genocidal."

As early as November 1907, the Canadian press was acknowledging that the death rate within Indian residential schools exceeded 50 percent. And yet the reality of such a massacre has been wiped clean from the public record and consciousness in Canada over the past decades.

But the real purpose of the policy was most clearly pointed out by Canadian Indian Affairs Superintendent Duncan Campbell Scott in 1910. "It is readily acknowledged that Indian children lose their natural resistance to illness by habituating so closely in these schools, and that they die at a much higher rate than in their villages," Scott lamented, "But this alone does not justify a change in the policy of this Department, which is geared towards the final solution of our Indian Problem."

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)