She's been on the hunt for her blood relatives for 25 years. No luck.

Zhang Weili, from the northeastern Chinese city of Harbin, didn't know her mother was Japanese until she was 14.

It was on a tempestuous day in the spring of 1984, following her grandmother's funeral, that an elderly woman named Zhang Yufang told the now 53-year-old that she was half Japanese. It turned out that her mother was a Japanese war orphan left behind in the final days of WWII. Weili was dumbfounded, yet this explained why her "mother" (stepmother) threw her clothes on the ground as far back as she could remember, why her father was always silent, and why her grandmother minced her words while on a hospital bed.

At that point, she realized that her grandma, a gaunt woman with smiling eyes, had no blood relationship to her. "It turned out she's my foster grandma, who had adopted my mother amid the chaos that followed the Japanese retreat to ports or train stations in the summer of 1945," Zhang Weili mused.

In the room within a Russian-style building where her grandmother Zhang Yuzhi had lived, Zhang Yufang – Zhang Yuzhi's younger sister – showed Weili's mother's photos to her for the first time. "She has a round face, with even bangs, in a black-and-white photograph," Weili described.

She later cried throughout the night, clutching the photos of a woman of whom she had little memory. Growing up amid indifference from her stepmother, she craved maternal love.

According to Zhang Yufang, her mother – Li Guimin – died of postpartum chills six days after giving birth to Weili. Her foster grandmother's mental health suffered subsequently. "My foster grandma lavished too much love on my mother to endure the pain of losing her, not to mention that my foster grandfather had killed himself by jumping into the river a few years before," Weili said.

For the teenager back then, the saga was too difficult to process. Part of her has since been haunted by illusions of her mother. She would touch everything her mother had left, even lie on the bed her mother used to sleep in. "Those items felt very intimate," Weili recalled. At the time, she'd hurry to her foster grandma's home every noon to take a nap in anticipation of a dream where her mother would appear. "I was excited when I dreamt about my mother walking toward me."

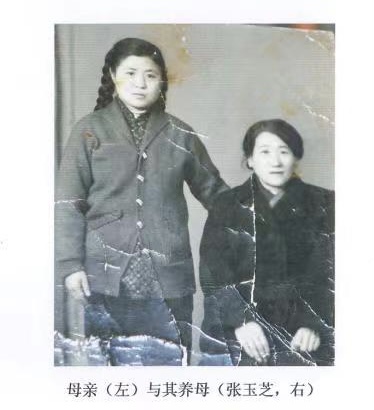

Li Guimin (L), a Japanese war orphan, and her foster Chinese mother Zhang Yuzhi pictured in Harbin, northeast China's Heilongjiang Province. /Courtesy of Zhang Weili

Li Guimin (L), a Japanese war orphan, and her foster Chinese mother Zhang Yuzhi pictured in Harbin, northeast China's Heilongjiang Province. /Courtesy of Zhang Weili

That was all she felt she could do. Later she learned that Li Guimin's father and brother had come from Japan to look for Li in the early 1980s, when the Chinese and Japanese governments both began to reunite war orphans with their families. Zhang Yuzhi said, "My Japanese girl has died." But she didn't tell them that Li had a daughter. They returned to Japan in grief, never to return to China.

"I understand. My foster grandma must have been afraid that she would never see me again if she had told them about my existence," Weili told us on a breezy evening in Harbin during our trip there.

Searching for blood bond

In 1993, Weili became a mother and increasingly missed her own mum. "She died giving birth to me. I owe my life to her. I must find her blood relatives. That might have been her wish as well."

In 1996, when her son was three years old and no longer needed round-the-clock care, she set out to search for her maternal blood relatives. Zhang Yufang took her to a village called Manjing in Bayan County where she painstakingly assembled shattered pieces of Li Guimin's backstory.

"My mother was the youngest of four children in a Japanese family that had moved there in the final years of the war under a massive emigration program of the then Japanese government."

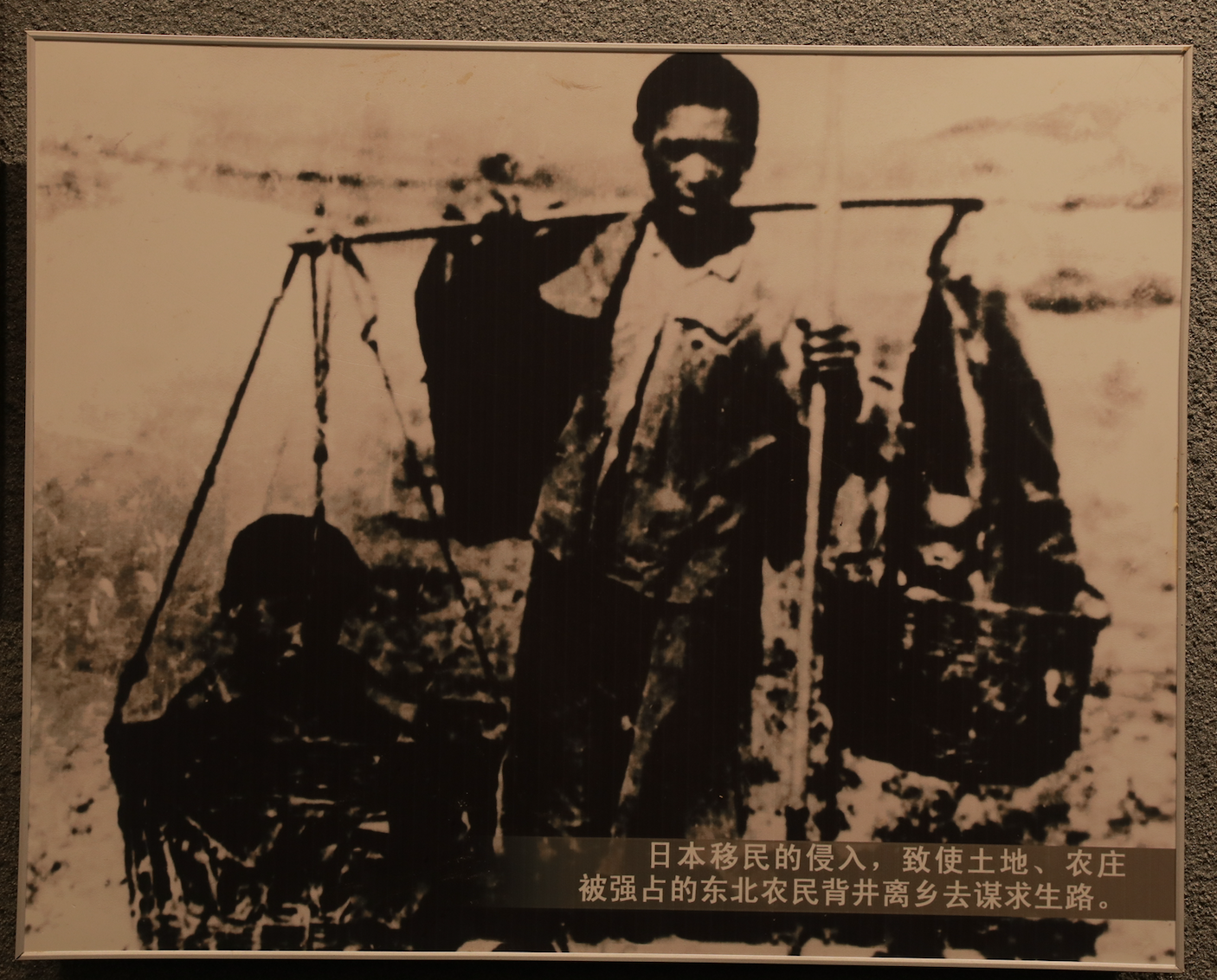

A photo describing the first emigration of Japanese to northeast China, organized by then Japanese government in 1932. Picture taken by CGTN at the September 18th History Museum in Shenyang, northeast China's Liaoning Province, April 26, 2021.

A photo describing the first emigration of Japanese to northeast China, organized by then Japanese government in 1932. Picture taken by CGTN at the September 18th History Museum in Shenyang, northeast China's Liaoning Province, April 26, 2021.

Legacies of war

The emigration program was a byproduct of the Japanese invasion of northeast China that began on September 18, 1931. The program grew after the Japanese established the puppet government of "Manchukuo," known as Manchuria, to control the vast territory, coveting its abundant farmland, minerals and energy resources. As part of its colonization efforts, the Japanese government initiated a five-year trial emigration plan and later announced the sending of 1 million households, roughly 5 million Japanese, to settle on the fertile Chinese soil over the next 20 years. Many families were deceived by prospects of a better life and instead became part of the Japanese army reserve to help fight its war.

In the words of Meng Yueming, a researcher who studies the population of Japanese war orphans at the Shenyang Academy of Social Sciences, "the emigration was actually the parallel relocation of a small Japanese society to China."

When the long, bloody war ended following Japan's surrender on August 15, 1945, some 4,000 Japanese children were left behind. Most of them, from newborns to teenagers, were the offspring of farmers and low-level Manchurian railway employees – underclass migrants abandoned by their Japanese government. During the retreat, these settlers, hounded by hunger and disease themselves, either gave up their children in hopes that kindhearted locals would adopt them or entrusted them to Chinese families they knew.

A photo of a Japanese family that had moved to northeast China during WWII; families like this were on the rise during wartime. Picture taken by CGTN in the September 18th History Museum in Shenyang, northeast China's Liaoning Province, April 26, 2021.

A photo of a Japanese family that had moved to northeast China during WWII; families like this were on the rise during wartime. Picture taken by CGTN in the September 18th History Museum in Shenyang, northeast China's Liaoning Province, April 26, 2021.

A photo of a Chinese peasant escaping home as Japanese emigrants came to occupy the land. Picture taken by CGTN in the September 18th History Museum in Shenyang, northeast China's Liaoning Province, April 26, 2021.

A photo of a Chinese peasant escaping home as Japanese emigrants came to occupy the land. Picture taken by CGTN in the September 18th History Museum in Shenyang, northeast China's Liaoning Province, April 26, 2021.

Li Guimin, a toddler in 1945, was fortunate to be placed with a family acquaintance. "My Japanese grandfather handed my mother over to Zhang Yuhua (cousin of Zhang Yufang and Zhang Yuzhi) on the way back to Japan with his two older sons. However, Zhang Yuhua's family was too poor to raise my mother and hence gave her to Zhang Yuzhi, my foster grandma," Weili recounted.

Zhang Yuzhi raised the girl as her own, protecting her from discrimination and keeping her identity a secret during the Cultural Revolution. Li Guimin later became a sugar factory worker, and in 1967 married a man who loved her very much, but her life ended suddenly just two years later.

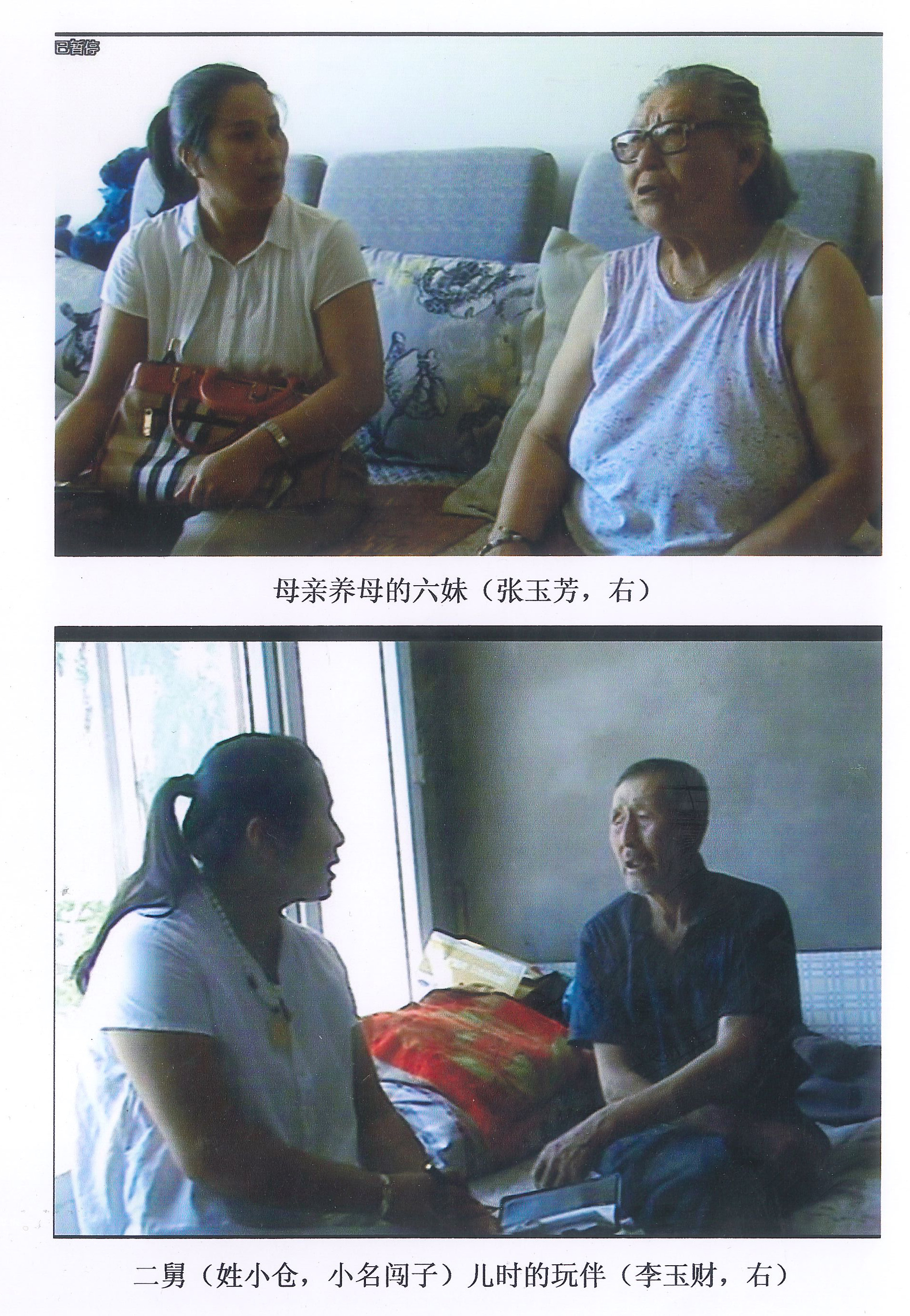

Photos of Zhang Weili and Zhang Yufang (R, top), a sister of Weili's foster grandmother; and Weili and Li Yucai (R), a friend of Weili's Japanese uncle, in the 1930s and 1940s. Both pictures were taken during Weili's search for her blood relatives. /Courtesy of Zhang Weili

Photos of Zhang Weili and Zhang Yufang (R, top), a sister of Weili's foster grandmother; and Weili and Li Yucai (R), a friend of Weili's Japanese uncle, in the 1930s and 1940s. Both pictures were taken during Weili's search for her blood relatives. /Courtesy of Zhang Weili

Weili went back to Harbin with the information and started collecting material about her mother's Japanese family. For two decades since then, she wrote numerous letters to Japan's Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, yet received no news because she couldn't prove she was Li Guimin's daughter. Hu Xiaohui, who founded an association for Harbin's foster parents of Japanese orphans, suggested she try to get hold of her family's household registration certificate. "When I came to the city's public security bureau and saw the small brochure where my name is next to my mother's, I burst into tears," she exclaimed.

Then she traveled to Manjing, again, hoping to find more clues from elderly villagers who knew people from the Japanese settlements. Li Yucai, in his 80s, said she looked like the youngest daughter of Ogura, whose family had lived in his house in the 1940s. "Altogether seven Japanese families resided in my home," Li Yucai recalled. "One of Ogura's sons was the same age as I was. We always played together."

With these clues, Weili sought out every visiting group of Japanese war orphans to find more details, bought books on the harrowing history of the war, learned to read Japanese books and to search on the internet. That was no easy job for her, a factory worker with only a junior high school diploma.

After much research and asking around, she gained a clearer understanding of her blood relatives: Her grandmother had a long neck as she did while a little girl, and her grandfather was also part of the Japanese military. Their hometown was probably in Japan's Mie Prefecture and they came to Manjing as part of a settlement called Yutoku.

Zhang Weili (2nd left, first row) with Japanese war orphans who helped her in her search for her family, during her trip to Japan in 2019. /Courtesy of Zhang Weili

Zhang Weili (2nd left, first row) with Japanese war orphans who helped her in her search for her family, during her trip to Japan in 2019. /Courtesy of Zhang Weili

Weili traveled to Japan twice. When the plane landed at Tokyo's Narita Airport, she took her mother's photo out to let her "see" her hometown.

In Taki-gun district in Mie in May 2018, she excitedly found in a 920-page book a list of names that were part of the Yutoku settlement in China at the time. But her hopes were quickly dashed when she read, "No official record could be found after a fire destroyed the list."

A year later, she set off again, to a town called Taiki, also in Mie. Meeting after meeting with emigrants who had returned to Japan after WWII gave her a glimmer of hope. "Masateru Itasawa, one of the elderly emigrants who had made it back to Japan decades ago, wrote below my mother's photograph: Father – Wakaichi Ogura, mother – Katsu Ogura, brothers – Yasuharu and Yasuaki Ogura, sister: Hatsumi Ogura."

Though tragic, Weili's story isn't entirely unique. The trauma from the war continues to affect people who are generations removed from those who had participated or were victims of the invasion. "When I was a little girl, all I wanted was a hug from my mother. Now that she passed away, I want a hug from blood relatives, nothing else," said Weili. Her desire may be a simple gesture, but she has spent much of her life looking for this approval. For Weili and others like her, the war is still very much a part of their lives.

As the pandemic has halted almost all international travel, Weili is waiting for another chance to travel to Japan to look for more clues. She is racing against the clock since not many war orphans will be around much longer. Yet even after all this time, the desire to learn about her heritage and family's past is as fresh as the day she learned the truth about her origins.

Reporters: Bi Junxin, Wang Xiaonan

Writer: Wang Xiaonan

Cover image designer: Yu Peng

If you have a story on Japanese war orphans and want to share it with us, please write to us at stories@cgtn.com.