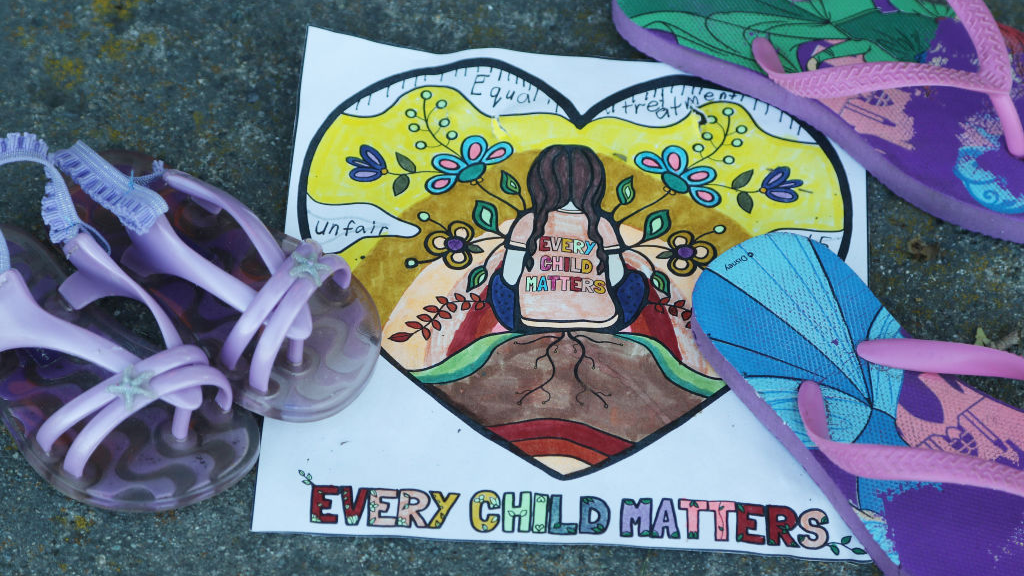

A "growing memorial" picture is seen as another Indigenous community in British Columbia says ground-penetrating radar has found human remains near a former residential school in Cranbrook, Canada, June 30, 2021. /Getty

A "growing memorial" picture is seen as another Indigenous community in British Columbia says ground-penetrating radar has found human remains near a former residential school in Cranbrook, Canada, June 30, 2021. /Getty

Editor's note: Stephen Ndegwa is a lecturer at the United States International University-Africa in Nairobi. He is also a communication expert, author and international affairs columnist. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

May will remain etched in the memory of the world as the month when more unmarked graves of indigenous children were discovered at the site of what was once Canada's largest residential school for them, compulsory, funded by the government and run by the church.

At the last tally there were over 1,100 such graves at several such schools in Canada. The shocking discoveries have led to indigenous groups demanding a nationwide search to see if there are more graves. These residential schools were established as a policy aimed at "assimilating" indigenous children by destroying their cultures and languages.

The backlash was swift, with several Catholic churches built on indigenous land bearing the brunt of the ensuing anger. Most of these institutions were run by the Roman Catholic Church. This time, the Western media did not try to whitewash the truth and referred to the saga, essentially the murder of innocents, as "cultural genocide."

This is just the tip of the iceberg. History is replete with horror stories of the original residents in the U.S. and Europe being decimated to give way to the New World. Historians say that European colonialism in the mid-20th century usually involved genocidal violence against indigenous groups in the Americas, Australia, Africa and Asia.

It was a two-step process. First came the physical extermination of indigenous people and their lifestyles. The surviving population was then forced to undergo a complete "cultural assimilation" that destroyed their identity and replaced it with that of their subjugators.

The United Nations (UN) defines indigenous people as those who inhabited a country or geographical region at the time when people of different cultures or ethnicity arrived. The new arrivals later became dominant through conquest, occupation, settlement or other means.

Besides these historical injustices, it is still a tough world for "original" people. The overwhelming and constant socioeconomic and technological changes have worsened their plight. In addition to facing the normal challenges everyone else does, the world's indigenous people face harsher realities due to their inadequate social and economic status, making them more vulnerable.

A cemetery in Cranbrook, British Columbia, Canada, June 30, 2021. /Getty

A cemetery in Cranbrook, British Columbia, Canada, June 30, 2021. /Getty

This has become more apparent since the devastations caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. While marking the International Day of the World's Indigenous Peoples on August 9, the UN said "a centuries-old marginalization and a set of different vulnerabilities expose indigenous peoples to the serious effects of the COVID-19 pandemic."

According to UNESCO, "indigenous peoples live in all regions of the world and own, occupy or use some 22 percent of global land area. With an estimated population of between 370-500 million, they represent the greater part of the world's cultural diversity, and have created and speak the major share of the world's almost 7,000 languages."

Basically, the world will be worse off if they become extinct. They have a special relationship with their lands and hold diverse concepts of development. As the UN has recognized, they are the custodians of a vast diversity of unique cultures, traditions, languages and knowledge systems. These are invaluable in tackling challenges like climate change and pandemics.

Ensuring their rights is a human rights imperative. While Western governments have a facade of progressive laws that protect and promote the rights of indigenous populations, the story on the ground is different.

Ironically, the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in northwestern China, much maligned by the West, is a benchmark of not just the protection, but also the empowerment of indigenous populations.

Home to about 25 million people and with a documented history of at least 2,500 years, it has seen governments at different levels involved in efforts to ensure leapfrog development in the region over the last 20 years. The program has seen the more developed areas in China pairing up with cities in Xinjiang to promote agriculture, industry, technology, education and health services.

Today, Xinjiang is a major producer of solar panel components. In 2020, it accounted for 45 percent of global production of solar-grade polysilicon. China provides 26 percent of global cotton exports and Xinjiang produces 84 percent of that, making it the world's largest cotton exporter. It is easy to see why the West envies the region.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)