After 20 years of digging in the trenches and fighting the almost imperishable Taliban, the U.S. has finally given up on Afghanistan, bringing a sordid close to its longest war in history. As the Taliban launched a lightening offensive that captured capital Kabul on Sunday, catching everyone off guard, images of retreating American helicopters had many media outlets dub it "Biden's Saigon moment."

Just over a month ago, U.S. President Joe Biden told the world confidently that a Taliban takeover of Afghanistan was "highly unlikely." The reason was because at 300,000 strong, Afghan soldiers were "as well-equipped as any army in the world." On the other hand, the number of sandal-wearing Taliban stood at only 75,000.

The turnout proved to be disastrous for the Afghan security forces. Much of the American military aide – the Black Hawks, Humvees, drones and other weapons – have gone to arming the Taliban, as the government forces quickly crumbled with little resistance. With the state-of-the-art firepower, the Taliban gained political power in a blitz.

Looking back at the enormous costs the U.S. paid in both economic and human terms, the result they produced is minimal, and absurd at times.

"We didn't fight a 20-year war in Afghanistan; we fought 20 incoherent wars, one year at a time, without a sense of direction," writes Mike Jason, a retired U.S. Army colonel in The Atlantic.

Afghans climb atop a plane as they wait at the airport in Kabul, Afghanistan, August 16, 2021. /AFP

Afghans climb atop a plane as they wait at the airport in Kabul, Afghanistan, August 16, 2021. /AFP

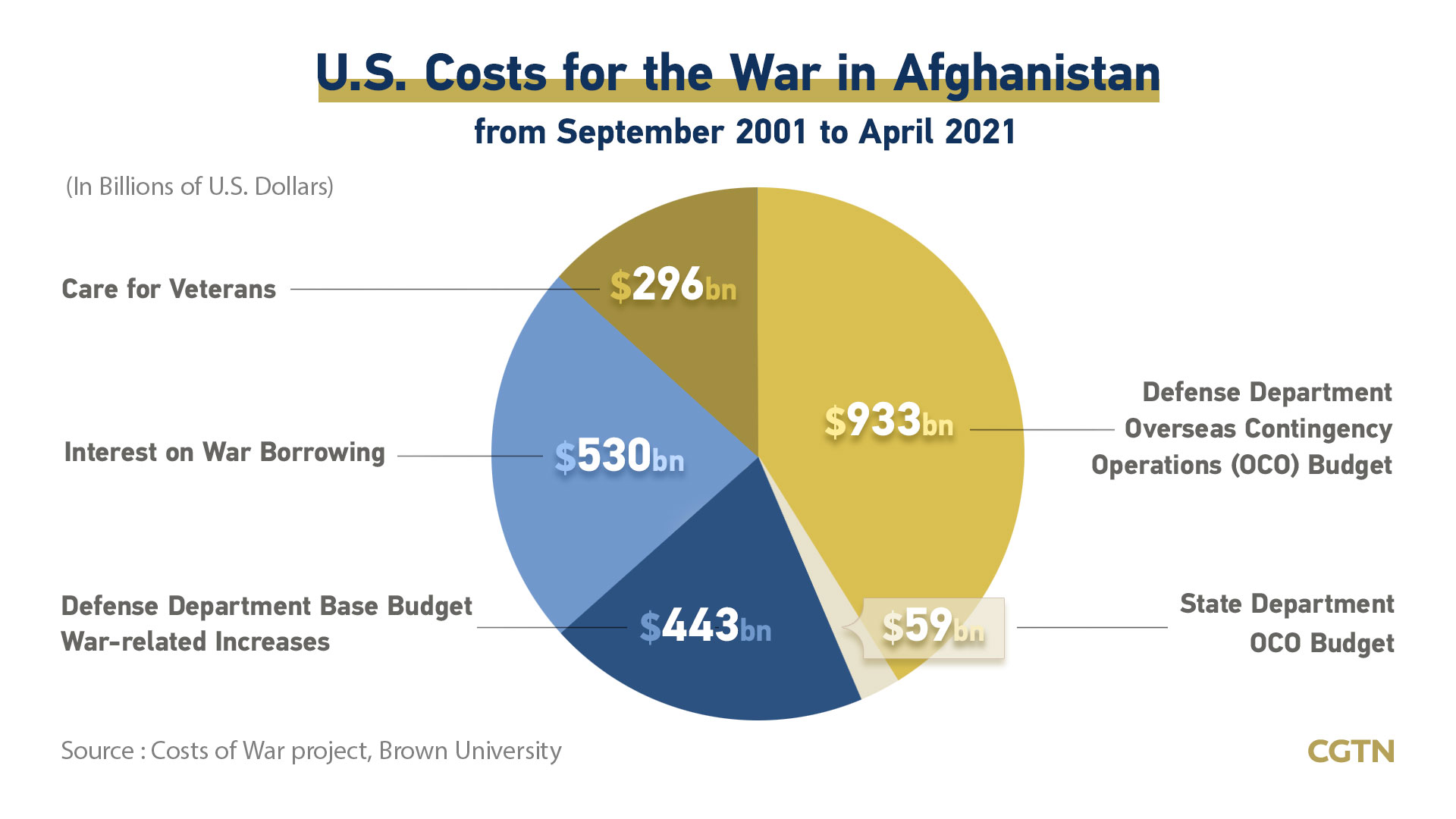

The U.S. has spent approximately $2.26 trillion on the war in Afghanistan, according to the estimates made by the Costs of War Project of Brown University this April when Biden announced full U.S. troops withdrawal. That translates into over $300 million per day, over the past two decades.

The exorbitant tally includes not just $933 billion devoted to Department of Defense overseas contingency operations, $443 billion in the department's base budget war-related increases and $59 billion in additional State Department funding, but an interest worth around $530 billion. It also covers $296 billion toward the medical and disability care for veterans, which has yet to come to an end after the end of the war. It's projected that additional $1 trillion will be needed over the next 40 years as the veterans age and need more healthcare services for not only physical debilitation but psychological traumas.

In addition, there's another expenditure, standing at $143 billion, on rebuilding the country, including $88 billion poured in building, equipping and training Afghan National Defense and Security Forces, according to Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction John F. Sopko.

Behind all this, American taxpayers are footing the bills, on average $750 million a year in payroll for Afghan soldiers. When the U.S. dispatched as many as 100,000 solders in the war-torn country between 2010 and 2012, the price was much dearer. What's more, American taxpayers are going to pay the price for many years to come, even decades, as the interest payments for this debt-financed war could exceed $6.5 trillion by the 2050s. That could constitute an overwhelming burden for the world's largest economy struggling to recover from the devastating pandemic.

Estimated spending of the U.S. on the Afghan war over the past 20 years, excluding interest payments and veterans' care in next decades.

Estimated spending of the U.S. on the Afghan war over the past 20 years, excluding interest payments and veterans' care in next decades.

The extravagance that the U.S. has invested to keep the Taliban at bay has largely gone up for smoke. As Sopko found, roughly $17 billion of American taxpayers' money went to the pockets of corrupted officials and ill-conceived projects that invariably failed. These include $150 million for private security and luxury housing for the Pentagon's business task force, $47 million for building a "Silicon Valley-type startup incubator" that "did nothing," and believe it or not, $6 million for airlifting nine Italian goats to the country and setting up a laboratory to certify their wool. It also remains unclear if these goats were eaten. These projects, as detailed in a ProPublica investigation, went on repeatedly and often without a shred of accountability or government oversight.

Perhaps the most useful way to understand these astronomical numbers is to look at how they could be used to benefit average Americans. The $456,000 police-training facility, which was so badly built that it melted in the rain, could have funded more than 180,000 dinners for kids from low-income families, for an entire summer, according to ProPublica. The $335 million spent on a power plant that Afghans have never used could have paid for the permanent housing for 37,000 homeless Americans.

Besides the tangible figures that can be reckoned in terms of dollars, there's a harrowing human cost. Over 2,400 soldiers and 3,800 contractors from the U.S. died between September 2001 and April 2021, which, however, pale in comparison with a death toll of roughly 241,000 people as a direct result of the war. They included civilians, journalists and humanitarian workers. Indirect casualties caused by a range of factors, from water and food shortage to diseases, remain unaccountable.

U.S. Army soldiers from the 1-506 Infantry Division set out on a patrol in Paktika province, situated along the Afghan-Pakistan border, November 2008. /AFP

U.S. Army soldiers from the 1-506 Infantry Division set out on a patrol in Paktika province, situated along the Afghan-Pakistan border, November 2008. /AFP

The lack of a sense of direction and leadership ran as a constant theme throughout the war. In closed-door meetings, senior American commanders voiced disapproval and criticism of the U.S. war effort in Afghanistan.

According to a Washington Post report in 2018, U.S. officials had no "clear objective" from the beginning of the invasion and struggled to understand the forces they intended to fight.

"We were devoid of a fundamental understanding of Afghanistan – we didn't know what we were doing," says Douglas Lute, a three-star army general who oversaw the Afghan war under both the Bush and Obama administrations, told Sopko in 2015. "What are we trying to do here? We didn't have the foggiest notion of what we were undertaking."

In the troves of confidential documents obtained by the Post, U.S. officials freely acknowledged that their war-fighting strategies were fatally flawed and that Washington wasted enormous amount of money trying to mold Afghanistan into an image they desired. In public, U.S. officials conjured up a picture that its efforts in rebuilding the country were making progress.

An internally displaced Afghan woman washes clothes outside her shelter on the outskirts of Kabul, Afghanistan, February 3, 2021. /Reuters

An internally displaced Afghan woman washes clothes outside her shelter on the outskirts of Kabul, Afghanistan, February 3, 2021. /Reuters

Two decades of war isn't nothing though. The U.S. helped build infrastructure projects, such as roads, bridges, power plants and telecom facilities, mostly in the country's urban areas. Girls can go to school and women can get a job. With an influx of economic aid, the shattered country witnessed fast economic growth for over a decade. Its GDP rose perpendicularly from $4 billion in 2002 to more than $20 billion in 2013, according to the World Bank.

Nonetheless, an economy founded on foreign aid can hardly sustain, especially given social insecurity, government corruption and a fragile business environment. Withering aid flows since 2009 has sent the Afghan economy on a roller coaster ride. Despite the aid, the world's largest economy failed to help this crappy economy get on its feet.

In 2020, the country's per capita GDP was $581, among the lowest in the world. Some 80 percent of Afghans live in destitute rural areas, with limited access to water and land rights. Many have to plant poppies to make a living because poppies, though illegal, are the top cash crop on the conflict-plagued, poverty-ridden land.

Recent escalations are reshaping the already most deadly place. "The situation is still very fluid," said Robert Mardini, director-general of the International Committee of the Red Cross, which is delivering urgently needed humanitarian aid there. "And it will take us time to meet the magnitude of the humanitarian needs."

Hospitals, either controlled by the then government or by the Taliban, are struggling with the same challenges: no electricity, no water, no fuel to run a generator, no medical and surgical equipment, Mardini noted.

At the same time, for civilians caught in the line of fire, there's the same level of fear, grief and frustration.

(Graphics by Xing Cheng)