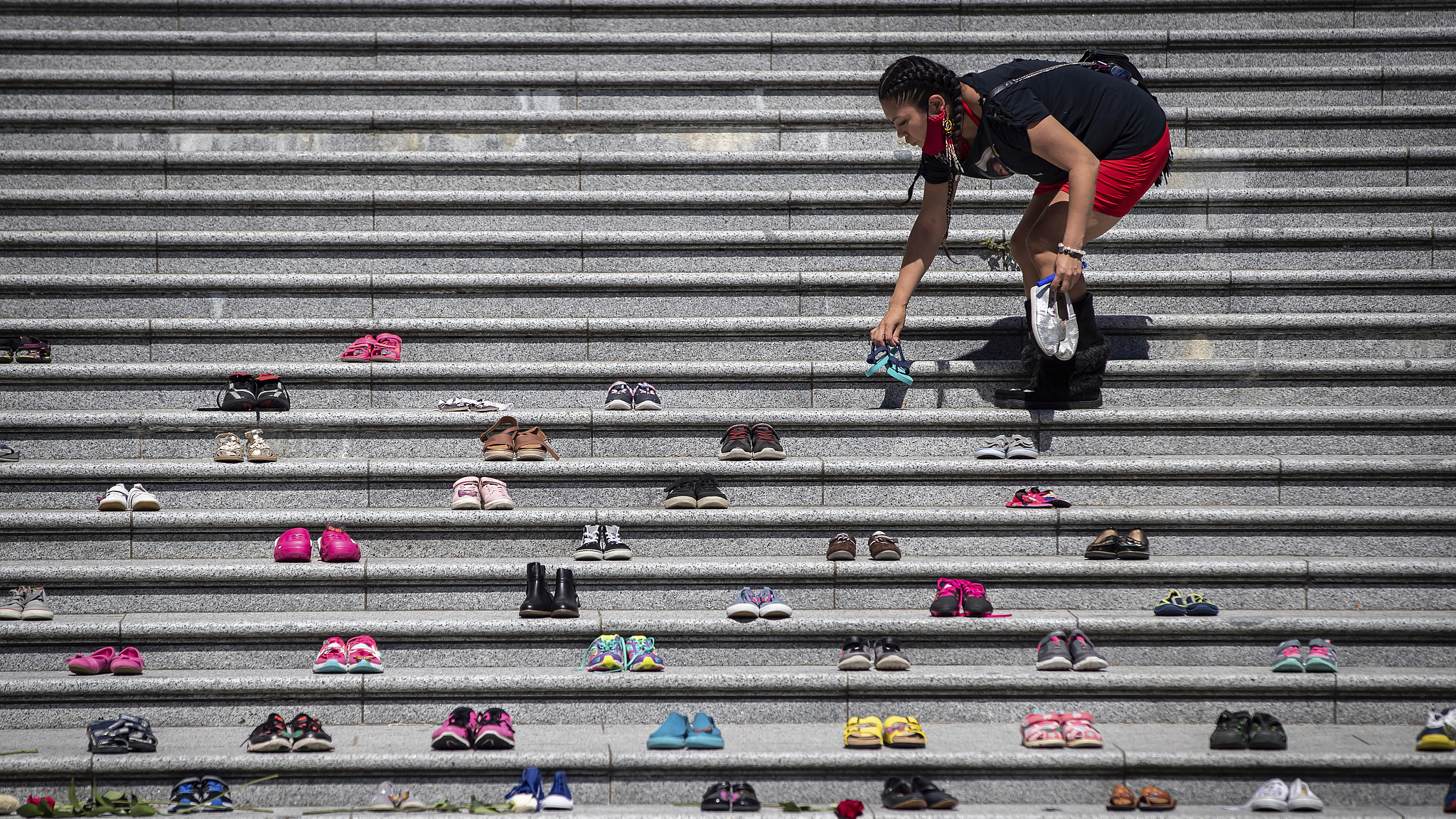

Children's shoes are placed on the steps of the Vancouver Art Gallery as a memorial to the indigenous children whose remains have been found near a former residential school in Kamloops, British Columbia, Canada, May 28, 2021. /CFP

Children's shoes are placed on the steps of the Vancouver Art Gallery as a memorial to the indigenous children whose remains have been found near a former residential school in Kamloops, British Columbia, Canada, May 28, 2021. /CFP

Editor's Note: The recent findings of over 1,000 unmarked graves near former indigenous residential schools in Canada once again came as a shock to the international community. Yet, many survivors say these are just the tip of the iceberg. The series intends to throw some light on Canada's dark past.

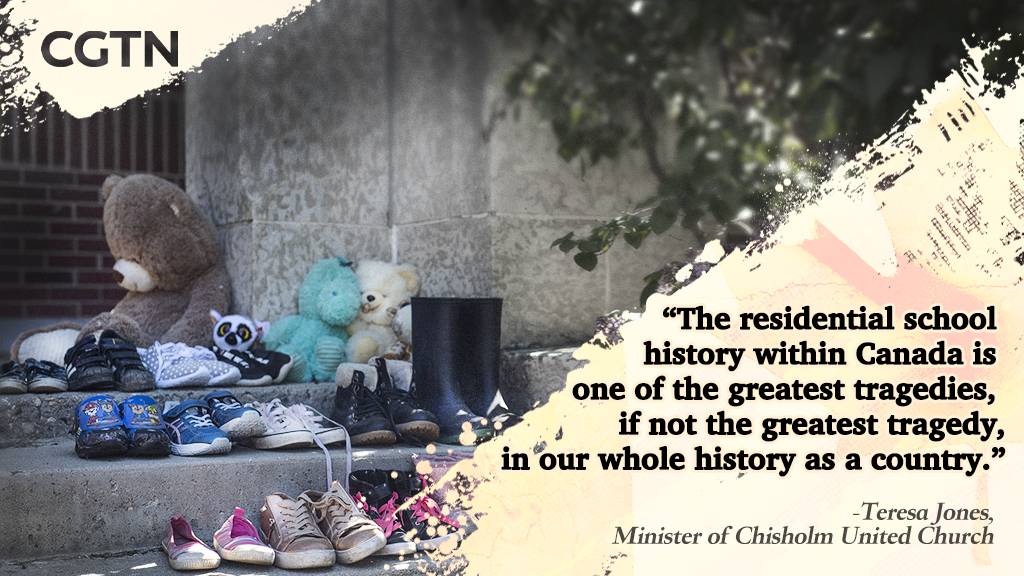

"The residential school history within Canada is one of the greatest tragedies, if not the greatest tragedy, in our whole history as a country," said church minister Teresa Jones at Lebanese filmmaker Rania Rafei's 40-minute documentary "Canada's Dark Secret" (2017).

The past months have seen over 1,300 unmarked graves discovered near the sites of former church-run indigenous residential schools in western Canada that appalled people across the world.

The latest finding was on July 12, when more than 160 unmarked graves were found around the Kuper Island Industrial School in British Columbia. Before that, remains of 182 indigenous children were discovered near St. Eugene's Mission School in British Columbia on June 30; around 751 unmarked graves were found near Marieval Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan on June 24; another 215 were found near the site of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia on May 27, some as young as three years old.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called these discoveries "a shameful reminder of the systemic racism, discrimination, and injustice that Indigenous peoples have faced and continue to face in this country."

Eradication of indigenous culture for over a century

After years of investigation and research, Canada's Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 2015 concluded that the establishment and operation of residential schools in the country can best be described as "cultural genocide."

"The schools were part of a larger effort by Canadian authorities to force Indigenous peoples to assimilate by the outlawing of sacred ceremonies and important traditions," said Murray Sinclair, a former Canadian senator and Chair of the TRC. "It is clear that residential schools were a key component of a Canadian government policy of cultural genocide."

Back in 1876, the Indian Act was passed by the Canadian government, aiming to administer and assimilate the country's indigenous population. Residential schools were then set up to serve the very purpose.

Some 150,000 indigenous school-age children across the country were forcibly taken away from their families and sent to these church-run boarding schools between 1863 and 1996, according to the TRC, where they were indoctrinated into the dominant Euro-Canadian and Christian way of life.

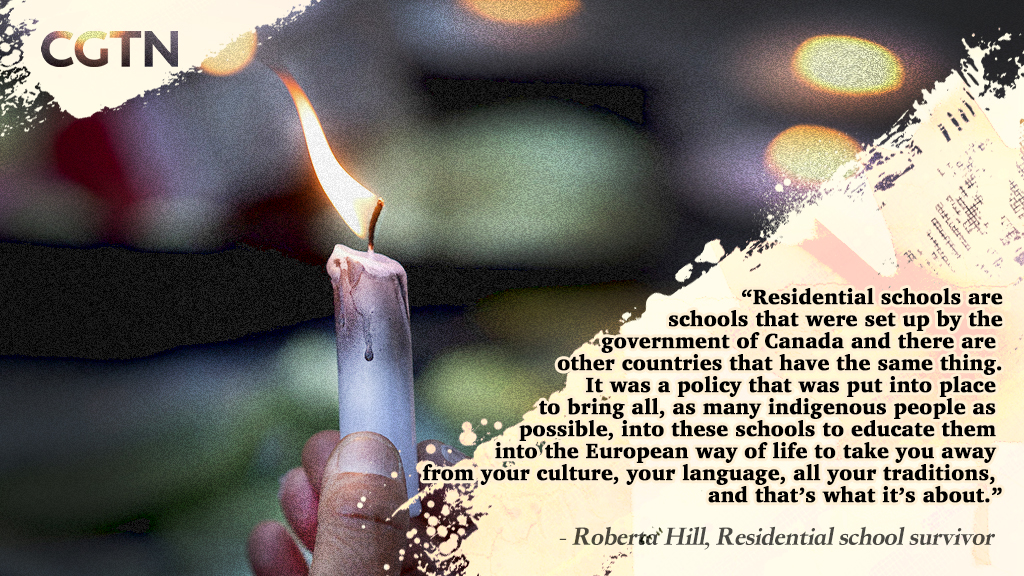

"In order to sever those ties in your culture, in your language, they had to separate children from families and communities," Roberta Hill, a residential school survivor, said in the documentary.

"We wore uniforms. We all dressed the same. You had your hair cut the same. You were all one," Hill recalled her school years at the Mohawk Institute Indian Residential School in Brantford, Ontario, from 1957 to 1961.

Students were banned from wearing traditional clothes or performing cultural practices, nor allowed to speak their mother tongue.

"They took us to the church every Sunday. We had to say prayers and things like that. We weren't allowed to talk in our language. We had to speak English," said Bud Whiteye, another residential school survivor.

As Canada's census in 2016 shows, 15.6 percent of the Aboriginal population in the country are able to converse in an Aboriginal language – a sharp drop from 21.4 percent in 2006. Many of the indigenous languages are spoken by less than 10,000 people, some by only hundreds.

A memorial on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, Canada, July 19, 2021. /CFP

A memorial on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, Canada, July 19, 2021. /CFP

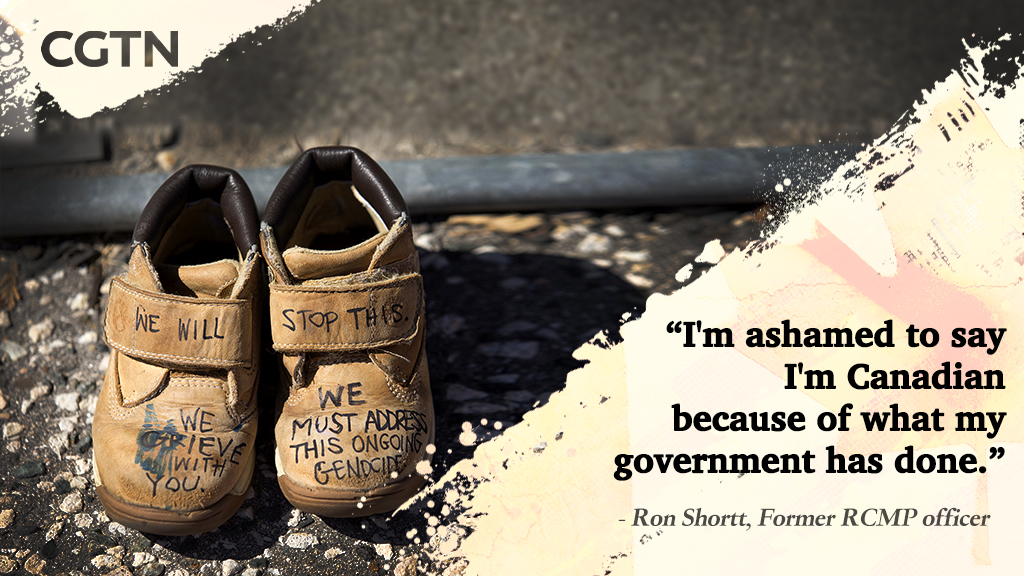

"I know from my own experience, people that I've known, they were raised by whites in the residential schools. So when they were finished there, their parents didn't accept them because they weren't native. And the white community did not accept them because they were native," Ron Shortt, former Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) officer said.

"So these people, 150,000 children, grew up in limbo with no roots, no background and no place they could call home," Shortt added.

From the 1980s, indigenous people in Canada began to speak out about their experiences at residential schools, and survivors launched a class-action lawsuit against the government.

In 2007, the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, the largest class-action settlement in the country's history, began to be implemented, and the TRC was established in 2008 to facilitate reconciliation among survivors, their families and communities.

Today, the search for more bodies of indigenous children continues across the country.

(Images designed by Yu Peng)