Editor's note:

The Afghanistan war ended just as it began. The country has once again come to a crossroads as the U.S. pulled its traumatized soldiers out of its longest war in history, with the Taliban riding back to power they had been stripped of 20 years ago. Afghanistan, a mountainous territory nestled in the heartland of Asia, has long been a battlefield of global powers. But it has never been conquered and hence had the sobriquet of the "Graveyard of Empires."

In this series, "Through the lens: Afghanistan 2001-2021," we dive into the scars the war has left on the country and the fear, wrath and resilience of the Afghan people. Our third article focuses on the country's rural economy and its top cash crop – the opium poppy. You can find the whole series here.

The tall, alluring poppy flower has scarlet red petals and a black heart. But don't be cheated by its captivating appearance. After being dried or boiled into a paste and blended with lime and stimulants in hot water, the silky flowers will become a morphine base which is made into heroin with tints of chemicals.

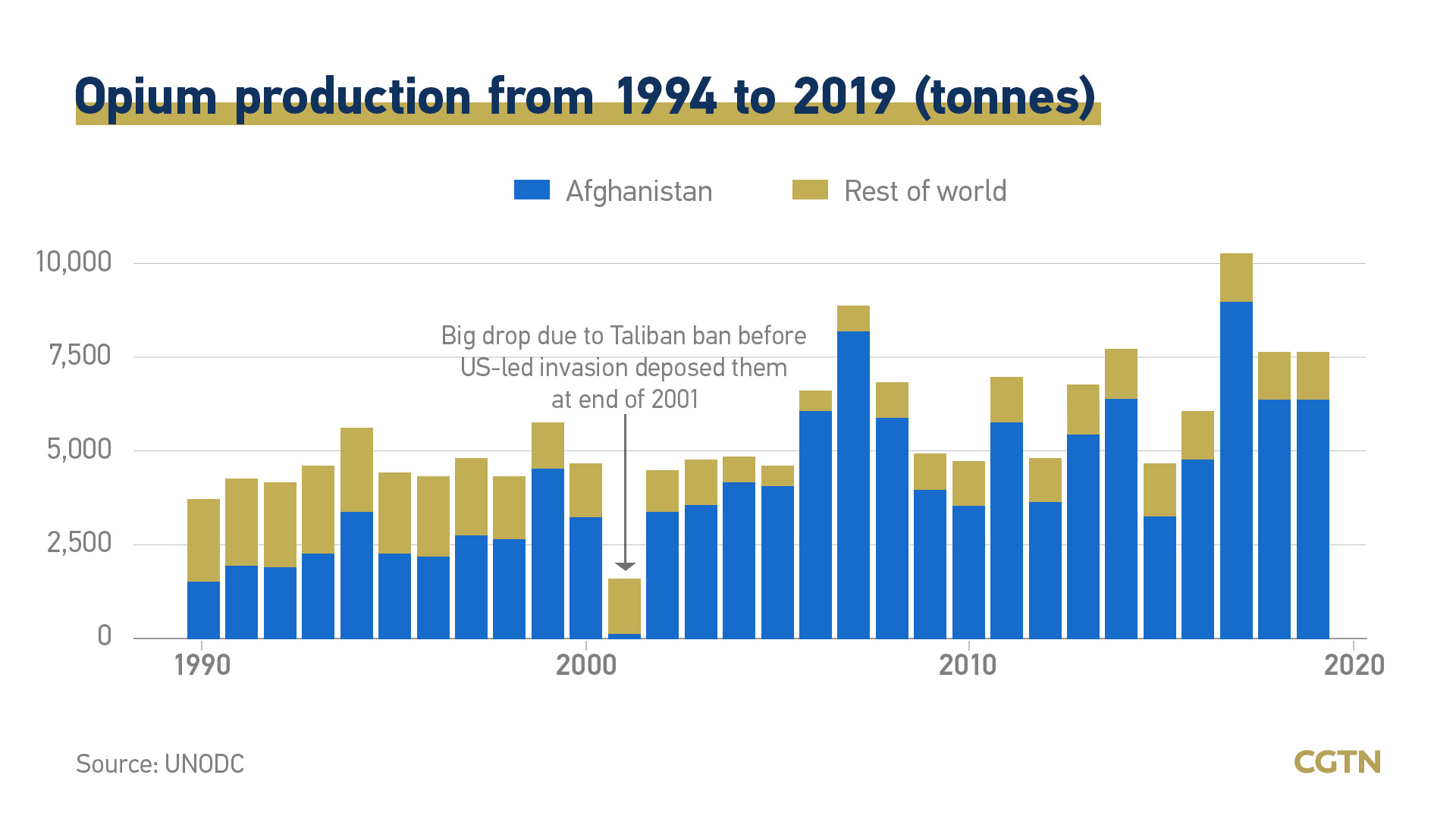

Poppy plantation has an established history in Afghanistan. For decades, foreign invasion and civil conflicts had brewed a mature industry of opium cultivation and drug trade. With plantation starting in scale in the 1950s, the sector boomed in the '80s amid the chaos following the withdrawal of Soviet troops. In 2000, the country's opium poppies made up 72 percent of the world's illicit opium.

Opium poppy flowers are in full bloom in a field in the eastern province of Nangarhar, Afghanistan, April 9, 2007. /Reuters

Opium poppy flowers are in full bloom in a field in the eastern province of Nangarhar, Afghanistan, April 9, 2007. /Reuters

An Afghan farmer harvests opium gum from a poppy field on the outskirts of Mazar-i-Sharif in Nangarhar, Afghanistan, in 2018. /AFP

An Afghan farmer harvests opium gum from a poppy field on the outskirts of Mazar-i-Sharif in Nangarhar, Afghanistan, in 2018. /AFP

The industry went through a temporary bust phase in 2001, hitting a record low, after the Taliban cracked down on opium production with a religious decree in July 2000. It declared planting poppies "un-Islamic," while some experts said they were seeking international legitimacy by doing so.

This downtrend was brought to an abrupt end by the September 11 attacks, which killed some 3,000 people and triggered Washington to formulate anti-terrorist initiatives. In the name of the "war on terror," the U.S.-led forces toppled the Taliban regime. Afghanistan was again shrouded in ashes.

Corrupt officials, warlords, drug traffickers and militant groups capitalized on the turmoil, fueling a resurrection of the opium industry. Given the complicated, unstable land ownership and management, destitute farmers, most of them with no land rights, were driven to work on poppy fields to make a living. That exacerbates the poverty cycle in rural Afghanistan, in particular exposing women and children to exploitation. In addition, structural unemployment has forced more into this business. Planting poppies could generate a profit 10 times higher than that of other crops.

Opium poppy cultivation reached a record high at nearly 330,000 hectares in 2007. Tens of millions of dollars in opium taxes are incurred every year, on which various forces cash in.

The Taliban is believed to have been involved in poppy planting, opium extraction, which could be up to 10 percent, in addition to charging drug smugglers shipment fees. In the meantime, former governments at all levels were also vying to make a profit. "It is widely alleged that corrupt officials within the Kabul government, the Afghan National Police, and various provincial administrations are also in the pay of opium traffickers," said a 2009 report by the U.S. Institute of Peace. The fierce scramble for profit and power leaves farmers few other options than to toil in the poppy fields.

Though the U.S. hardly talked about the need to address the illicit trade in public, it spent $8.6 billion to stamp out the opiate trade, according to John F. Sopko, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction. But it has rarely worked since impoverished Afghans need it to feed their families.

Former Afghan President Hamid Karzai once said, "Either Afghanistan destroys opium, or opium will destroy Afghanistan."

Afghan women work in a saffron field in Herat, Afghanistan, where at one point, former poppy farmers switched to growing the costly spice in 2013. /AP

Afghan women work in a saffron field in Herat, Afghanistan, where at one point, former poppy farmers switched to growing the costly spice in 2013. /AP

An Afghan policeman destroys poppies in Kunar province, April 29, 2014. /Reuters

An Afghan policeman destroys poppies in Kunar province, April 29, 2014. /Reuters

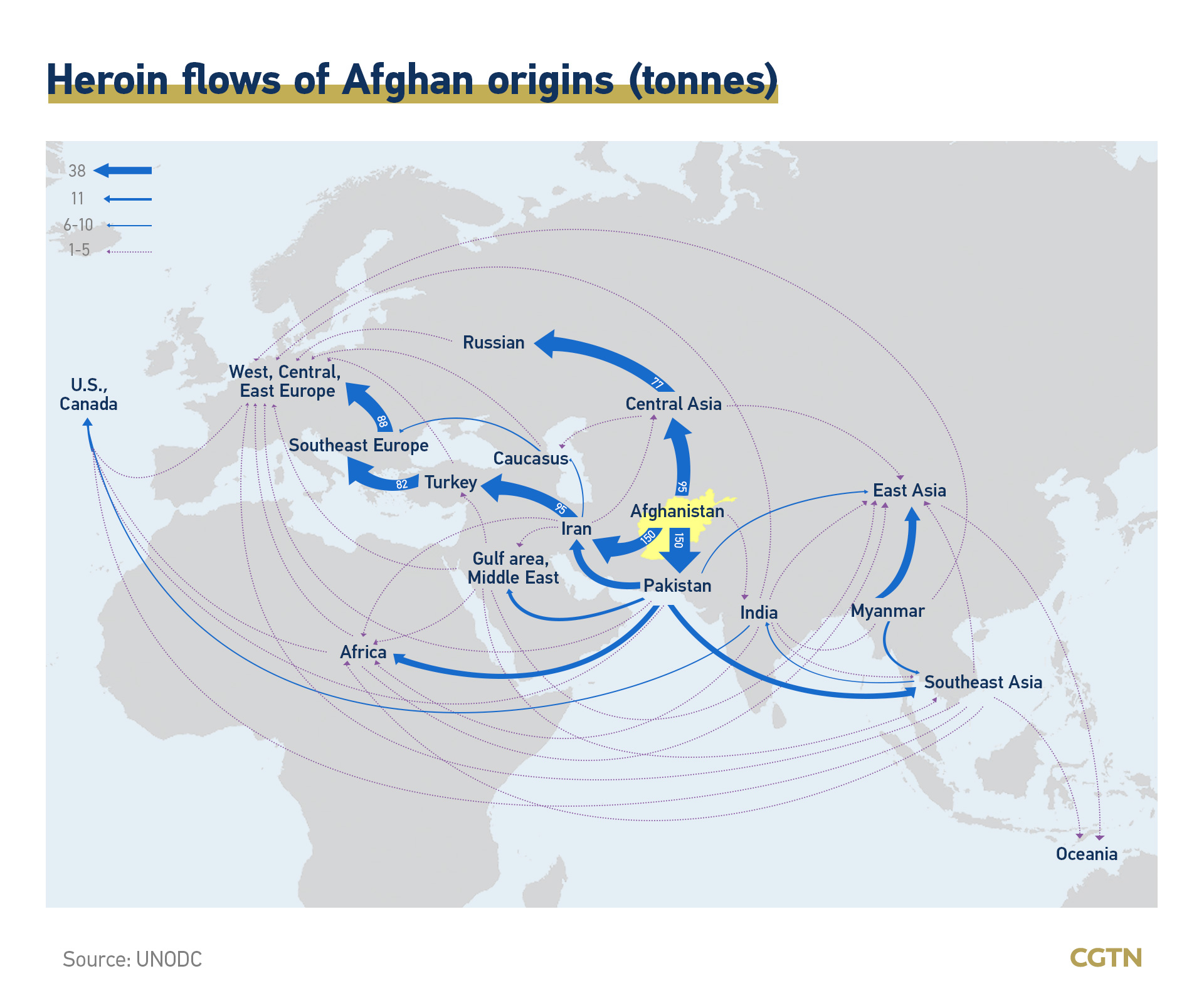

According to estimates by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), half of the country's GDP has been generated by the opiate economy. One in 10 Afghans is engaged in cultivation or the drug trade, which has largely shaped the modern Afghan economy. The trade has also generated lucrative profits outside Afghanistan, as it's estimated to account for more than 80 percent of the global opium business.

In 2017 Afghanistan's opium harvest surged to 9,000 metric tons, while in 2001, it was only 180 metric tons. A year later, the production witnessed a sharp drop due to a severe drought and household income in gravely affected rural areas fell by half. However, the opiate economy "was still worth between 6 and 11 percent" of the country's GDP and provided "the equivalent of up to 190,700 full-time jobs" in that year, as was written in the UNODC's Afghanistan opium survey 2018.

The latest statistics on opium poppy revealed a steady rise. Despite the pandemic, the poppy cultivation area was estimated at 224,000 hectares, an increase of 37 percent year on year. Twenty-two out of the country's 34 provinces have poppy fields.

A local farmer displays packages of opium after harvesting it from his poppy fields in the Surkh-Rod district of Nangarhar province, Afghanistan, June 28, 2020. /AFP

A local farmer displays packages of opium after harvesting it from his poppy fields in the Surkh-Rod district of Nangarhar province, Afghanistan, June 28, 2020. /AFP

Afghan drug addicts prepare heroin to use by injecting, at an abandoned building in Kabul, September 30, 2007. /Reuters

Afghan drug addicts prepare heroin to use by injecting, at an abandoned building in Kabul, September 30, 2007. /Reuters

Along with the growth of opium production is opium addiction. War, poverty and migration, and easy access to opium, also led more and more Afghans to use drugs. The UN estimates that up to 2.5 million people regularly use drugs, most of whom have quite limited access to treatment.

It seems that as instability continues to haunt the country with the Taliban and opposition forces still in battle, the Afghan economy will continue being addicted to opium. The complex confluence of factors – poverty, war-related trauma, lack of job opportunities – will hardly end the opium poppy business any time soon, despite the Taliban's pledge to throttle it.

The rural poor have to be given economic alternatives to sustain their life before they come to a cul de sac.

Afghan girls are increasingly becoming casualties of the country's drug trade. /Reuters

Afghan girls are increasingly becoming casualties of the country's drug trade. /Reuters

The consequences of drug addiction are all too clear to see in Kabul and elsewhere in the world. /Reuters

The consequences of drug addiction are all too clear to see in Kabul and elsewhere in the world. /Reuters

Du Junzhi contributed research.

Graphics: Yang Yiren

Cover image designer: Liu Shaozhen