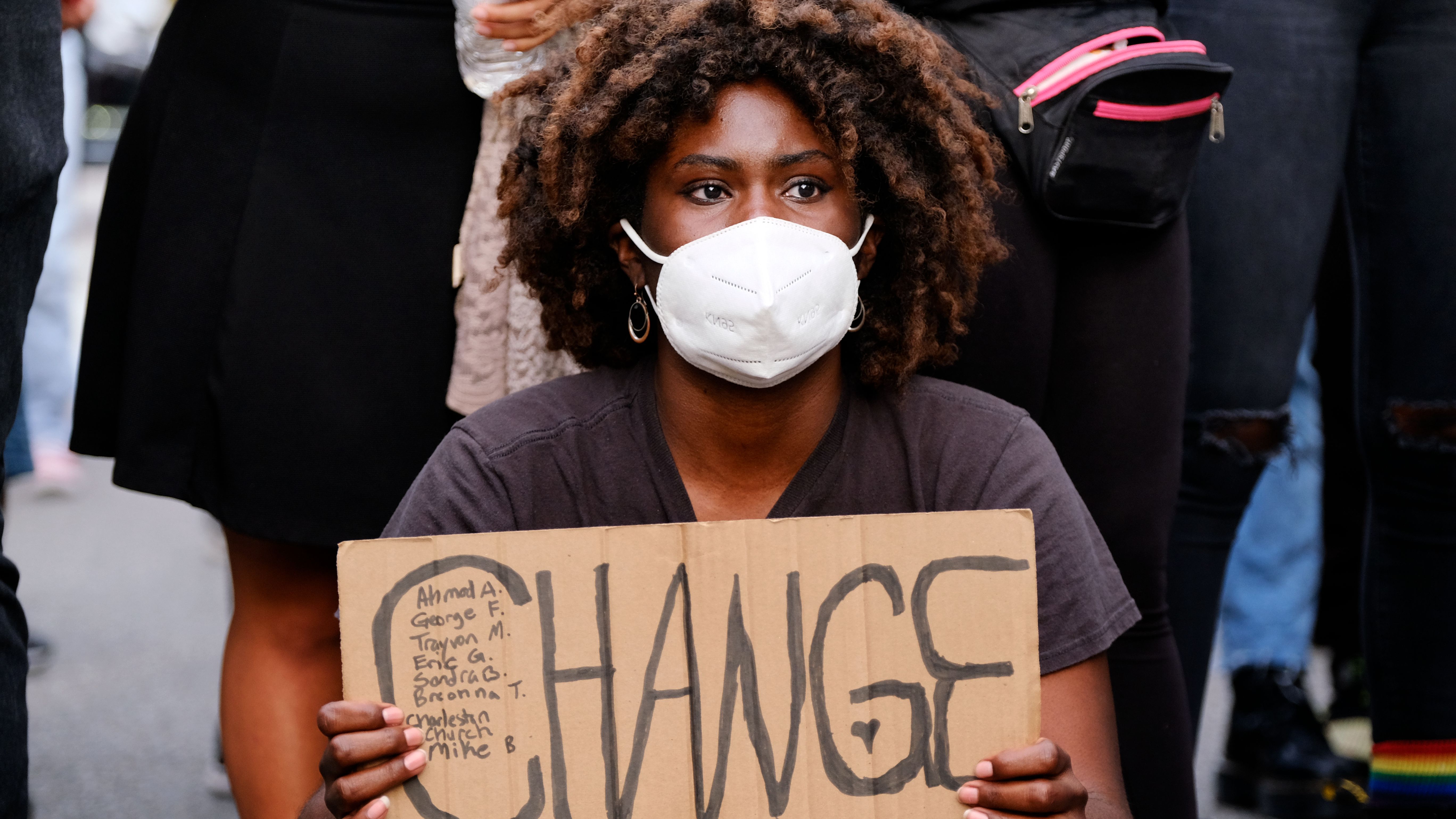

A Black Lives Matter protester holds a sign for change over the death of George Floyd in Los Angeles, June 2, 2020. /AP

A Black Lives Matter protester holds a sign for change over the death of George Floyd in Los Angeles, June 2, 2020. /AP

Editor's note: Bradley Blankenship is a Prague-based American journalist, political analyst and freelance reporter. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

In the past year, the United States has seen a huge amount of turmoil over the issue of race, though certainly the issue has persisted for its entire history. The extrajudicial murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, by a white police officer was the impetus for worldwide protests that changed the conversation on race under the slogan, "Black Lives Matter."

Still, realities in the United States have made clear that, at least in terms of how the socioeconomic system operates, minorities don't matter the same as whites.

This is evident by the fact that racial minorities in the U.S. have been disproportionately affected both in terms of health outcomes and economic prospects from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. What's more, racial minorities in the United States will also bear the brunt of the negative impacts of climate change, according to an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) report published recently.

This is not an abstract, far-off concept since the report comes just days after Hurricane Ida rocked low-income Black communities in Louisiana and Mississippi. But the results of the analysis suggest that such events will become more frequent, showing that a large percentage of minority communities are situated in areas that will be affected by floods, rising heat, pollution and thus rising mortality.

Given the stakes, this report by the EPA should be a warning signal to policymakers – both in the U.S. and around the world, because it reflects historical, deliberate inequality.

In the case of the U.S., minorities have been purposely segregated – as a matter of federal and local government policy – in areas that are the most environmentally unsafe. In fact, an executive order signed by President Joe Biden a week after coming into office sought to address these burdens faced by minority communities that were segregated into unsafe places, such as coal plants, railway depots and toxic chemical factories.

Damaged homes in floodwater after Hurricane Ida in Pointe-Aux-Chenes, Louisiana, U.S., September 2, 2021. /CFP

Damaged homes in floodwater after Hurricane Ida in Pointe-Aux-Chenes, Louisiana, U.S., September 2, 2021. /CFP

However, this is nowhere near enough. Existing inequalities will only deepen without more meaningful legislation, which in the context of the U.S. means an initiative from Congress since it holds the ability to allocate resources from the federal budget. That's because minority communities generally don't have the same economic wherewithal to adapt to climate change in the way that white communities do. This means that as the deleterious effects of climate change worsen, minorities will be stuck while whites will simply move to safer areas of the country.

This is essentially what late Nobel Prize-winning human rights activist Archbishop Desmond Tutu famously described as a "climate apartheid," though his use of the term applied to the global level.

At that global level, it's also important to see how historical inequalities have segregated the climate crisis. The most obvious observation is that while it's almost exclusively formerly colonized countries that are the most affected by climate change, it's mostly a few dozen countries that have historically benefited from colonialism that have produced the most greenhouse emissions (at least in per capita terms).

To illustrate just how absurd this is, an Oxfam report from September 2020 found that the world's wealthiest 1 percent produced twice as much carbon dioxide than the poorest 50 percent from the years 1990 to 2015. That is to say that the people who have contributed the least to the destruction of our planet are the most likely to suffer as a result, which is the most obvious example of injustice one could possibly imagine.

In order to correct this injustice, the world, particularly in the Global North, needs to get to work on climate change in a variety of ways that also address historical injustices in the past that still permeate the present.

It means reducing carbon emissions, cutting down on pollution, adopting clean energy solutions, as well as creating a restructured green economy, working toward multilateral solutions on the issue of climate refugees – and engaging in ambitious redistributive policies that help historically exploited countries and communities adapt to climate change.

Multilateral institutions like the United Nations have existing frameworks for several of these issues, seen in programs like the UN Green Climate Fund and the Global Compact for Migration. Though indeed useful starting points, it will still take far more political will from Global North to help realize the vision of these programs.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)