Editor's note:

The Afghanistan war ended just as it began. The country has once again come to a crossroads as the U.S. pulled its traumatized troops out of its longest war in history, with the Taliban riding back to power they had been stripped of 20 years ago. Afghanistan, a mountainous country nestled in the heartland of Asia, has long been a battlefield of global powers. But it has never been conquered, and hence had the sobriquet of the "Graveyard of Empires."

In this series, "Through the lens: Afghanistan 2001-2021," we dive into the scars the war has left on the country and the fear, wrath and resilience of the Afghan people. Our fifth article focuses on the devastating consequences of the war for Afghan civilians, the struggle for food and unemployment, the compromised rights for education, and the injuries and deaths that become mere numbers in news media reports. You can find the whole series here.

A boy carries his belongings next to the rubble of his home which was destroyed in a U.S. airstrike in the village of Azizabad in the Shindand district of Herat province, Afghanistan, August 23, 2008. /AP

A boy carries his belongings next to the rubble of his home which was destroyed in a U.S. airstrike in the village of Azizabad in the Shindand district of Herat province, Afghanistan, August 23, 2008. /AP

In the protracted war in Afghanistan, no one suffered more than Afghan civilians. Hundreds of thousands were forced to flee from homes with no shelter and rarely any food.

Since the beginning of the war, more than 48,000 civilians had been killed and 75,000 injured. Both numbers were likely a significant undercount, according to a report by the U.S. Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction in August 2021.

On October 7, 2001, the U.S. and British forces began a bombing campaign against al-Qaida, and the Taliban followed using its ground forces. This year, around 20,000 Afghan civilians lost their lives, with one-fifth of them dying in the first three months.

"The bombing was very severe. They mainly hit targets, but the force of the explosions was so intense ... My children used to rush to me. I could feel their hearts pounding like a little bird in your hand," Gholam Rassoul from the city of Herat who experienced the bombing told The Guardian.

Children and their parents run away after an explosion in Kabul, Afghanistan, May 24, 2013. /Reuters

Children and their parents run away after an explosion in Kabul, Afghanistan, May 24, 2013. /Reuters

As the war unfolded, the number of civilian deaths increased as a result of coalition military operations. In 2009, the UN mission in Afghanistan recorded the highest number of civilian casualties since the fall of the Taliban in 2001.

An Afghani girl looks at U.S. Marine Captain Micajah Caskey, from 8th Marine Regiment, while he talks with her father during a foot patrol in Garmsir district in Helmand province, Afghanistan, October 5, 2009. /Reuters

An Afghani girl looks at U.S. Marine Captain Micajah Caskey, from 8th Marine Regiment, while he talks with her father during a foot patrol in Garmsir district in Helmand province, Afghanistan, October 5, 2009. /Reuters

The U.S. military, in very rare instances, has acknowledged that harming Afghan civilians is inevitably part of its military strategy. From 2015 to 2019, the U.S. has made 455 "condolence payments" totaling more than $2,000,000 to Afghan civilians as "part of an expression of condolences, sympathy or goodwill, rather than as a means or compensation of reparation."

Details about the incidents that related to the payments are not publicly available, and payouts vary widely. In 2014, the U.S. military paid an Afghanistan man only over $1,000 to compensate for killing his son in an operation near the border with Iran. Haji Allah Dad, a 68-year-old man who has lost 20 relatives in a U.S.-led military operation, received no money from the U.S. military or the Afghan government.

From 2017 to 2019, the U.S. relaxed its rules of engagement in airstrikes and cut the number of troops in Afghanistan as part of its military strategy. Again, civilians paid the cost. Child deaths reached a record high in 2018, accounting for 28 percent of all civilian casualties.

Airstrikes declined in 2020 after the U.S. and the Taliban reached a peace agreement on February 29 that paved the way for a drawdown of U.S. troops and with a guarantee from the Taliban that the country would not be used for terrorist activities.

Local residents go through belongings left behind after deadly bombings outside a school in Kabul, Afghanistan, May 8, 2021. /AP

Local residents go through belongings left behind after deadly bombings outside a school in Kabul, Afghanistan, May 8, 2021. /AP

When international military forces began to withdraw, fighting intensified with the Taliban starting to take territories from the government forces. A dramatic rise in casualties occurred.

The UN mission in Afghanistan reported that a record number of children and women had been killed or wounded in the first half year of 2021 – a 47-percent increase year on year.

Afghan children sit near their home in Herat, November 30, 2014. As winter sets in across Central Asia, many Afghans struggle to provide adequate food and shelter for their families. /AFP

Afghan children sit near their home in Herat, November 30, 2014. As winter sets in across Central Asia, many Afghans struggle to provide adequate food and shelter for their families. /AFP

Those who survived the bombing and gunshots headed into the struggle of staying alive.

Widespread panic occurred in 2007 as bread prices soared over 90 percent. Though it kept in line with the global wheat price increase in the same period, it was too much for more than half of 25 million Afghans who lived on less than $1 a day.

There was little sign of progress. Surveys revealed that the proportion of the population living below the national poverty line is 55 percent during 2016-2017. In 2020, over 47 percent of the population still lived below the poverty line.

A boy works at a brick-making factory outside Kabul, Afghanistan, July 15, 2010. Laborers, most of whom work barefoot and without gloves, earn from $3 to $8 a day depending on their work hours and the number of bricks they make. /Reuters

A boy works at a brick-making factory outside Kabul, Afghanistan, July 15, 2010. Laborers, most of whom work barefoot and without gloves, earn from $3 to $8 a day depending on their work hours and the number of bricks they make. /Reuters

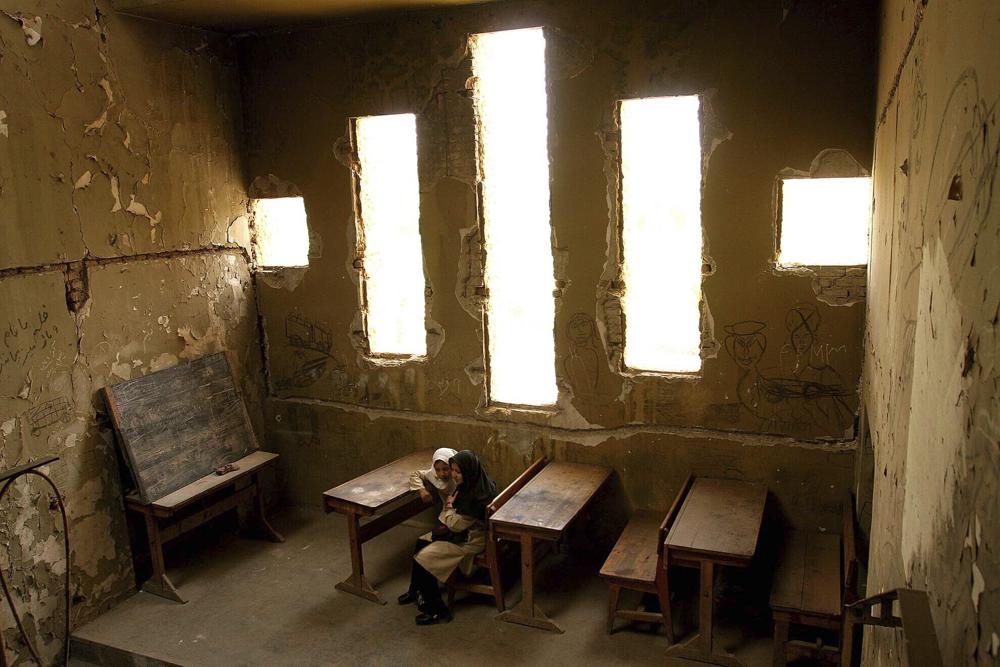

Basera, 13, right, and Saira, 10, wait for their class to begin at the Loy Ghar school in the bombed-out carcass of the Kabul Theater in Kabul, Afghanistan, April 20, 2005. The bullet-riddled building has become a place of hope for more than 400 students looking to rebuild their lives after decades of war. Classrooms have sprung up near windows or where bombs have destroyed enough of the wall to allow in sunlight. /AP

Basera, 13, right, and Saira, 10, wait for their class to begin at the Loy Ghar school in the bombed-out carcass of the Kabul Theater in Kabul, Afghanistan, April 20, 2005. The bullet-riddled building has become a place of hope for more than 400 students looking to rebuild their lives after decades of war. Classrooms have sprung up near windows or where bombs have destroyed enough of the wall to allow in sunlight. /AP

For a lot of Afghan children, attending school remained a distant dream. The educational system was devastated by years of conflicts, while attacks continued threatening normal teaching. For girls, barriers were higher.

Among two million primary school-aged children who did not attend school, 1.3 million are girls. Girls who got married at a young age are much more likely to drop out early.

In 2020, nearly half of 18,000 schools still lacked proper buildings. Many schools did not have water, sanitation and separate toilets for boys and girls.

Afghan girls study at an open area, founded by the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC), outside Jalalabad, Afghanistan, September 16, 2015. /Reuters

Afghan girls study at an open area, founded by the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC), outside Jalalabad, Afghanistan, September 16, 2015. /Reuters

Afghan students attend an open-air class at a primary school in Kabul, Afghanistan, October 7, 2020. /AP

Afghan students attend an open-air class at a primary school in Kabul, Afghanistan, October 7, 2020. /AP

Unending conflicts made this poverty-stricken country more vulnerable to new turbulence.

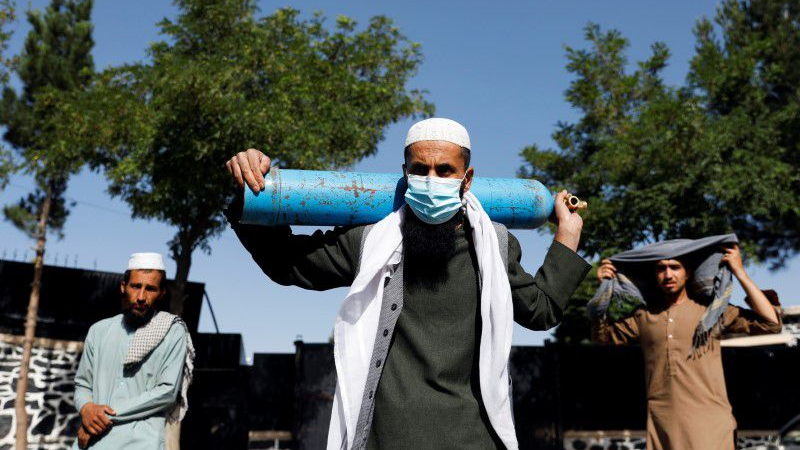

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, the country fell on harder times. In June 2021, new cases by 2,400 percent in a month, filling up hospitals and using up medical resources.

A man waits outside a factory to get his oxygen cylinder refilled, holding it on his shoulder amid the spread of COVID-19 in Kabul, Afghanistan, June 15, 2021. /Reuters

A man waits outside a factory to get his oxygen cylinder refilled, holding it on his shoulder amid the spread of COVID-19 in Kabul, Afghanistan, June 15, 2021. /Reuters

After the Taliban takeover in August, anxiety over security and inflation rocketed. Many didn't receive messages of resuming work. They had to line up outside banks to take out their money to get through. Unemployment and food supply crisis are looming.

People line up in front of a bank in Kabul, Afghanistan, August 31, 2021. /Xinhua

People line up in front of a bank in Kabul, Afghanistan, August 31, 2021. /Xinhua

The invisible wounds the war inflicted are the hardest to heal.

In 2019, the UN Human Rights Watch said about half of the population suffered from psychological distress, including depression, anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder. Children are deeply traumatized as they've witnessed atrocities committed against their families and others in their communities.

An Afghan girl carries her sister as she looks at a Canadian soldier on patrol while their father is being interrogated at his shop at Bazaar e Panjwai in Kandahar, May 28, 2009. /Reuters

An Afghan girl carries her sister as she looks at a Canadian soldier on patrol while their father is being interrogated at his shop at Bazaar e Panjwai in Kandahar, May 28, 2009. /Reuters

An Afghan boy cries during a funeral of members of his family in Logar province, March 27, 2013. /Reuters

An Afghan boy cries during a funeral of members of his family in Logar province, March 27, 2013. /Reuters

A national survey on depression and anxiety disorders in Afghanistan in 2021 shows that nearly 65 percent of population has experienced at least one traumatic event, and more than 78 percent witnessed one such event.

Even in the absence of fighting, unexploded ordnance and landmines posed a threat. An average 120 Afghans, including children, were killed or maimed by explosives every month, the Directorate of Mine Action Coordination of Afghanistan said. The figure was 40 every month in 2001.

Moreover, the ordnance left by the war caused a toxic environment, including substances that lead to higher risk of cancer and other diseases. It contaminates more than 1,600 square kilometers of land that may never get a full cleanup.

Editors: Wang Xiaonan, Zeng Ziyi

Cover image designer: Liu Shaozhen