Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison addresses the media during a press conference at Kirribilli House in Sydney, Australia, July 08, 2021. /Getty

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison addresses the media during a press conference at Kirribilli House in Sydney, Australia, July 08, 2021. /Getty

Editor's note: Daryl Guppy is an international financial technical analysis expert and national board member of the Australia China Business Council, who has provided weekly Shanghai Index analysis for mainland Chinese media for more than a decade. He also appears regularly on CNBC Asia and is known as "The Chart Man." The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

"Blindsided; hung out to dry; left out on a limb; pulled the rug out from under; left in the lurch; flat-footed." These are some of the multitude of English terms used to describe the situation where your best friend does something behind your back.

Australians can take their pick of these terms after the recent phone call between U.S. President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping, which has all the hallmarks of pirouette in policy that has caught Australia "flat-footed." It appears that Australian hawks have been shot down by their closest ally with White House reports saying "The two leaders had a broad, strategic discussion in which they discussed areas where our interests converge, and areas where our interests, values, and perspectives diverge."

"They agreed to engage on both sets of issues openly and straightforwardly. This discussion was part of the United States' ongoing effort to responsibly manage the competition between the United States and the PRC."

The two leaders discussed the responsibility of both countries to ensure "competition does not veer into conflict." It's an approach consistent with Biden's nomination of career diplomat Nicholas Burns, rather than a political colleague, to serve as U.S. ambassador to China.

This more conciliatory approach stands in contrast to the bellicosity of Australian relations with China, where apparently no compromise is possible.

In April, the Australian Home Affairs Secretary Michael Pezzullo delivered a "drums of war" speech, and a group of government members echoed the sentiments. These comments were never disavowed by Prime Minister Scott Morrison or his colleagues. Last week Defense Minister Peter Dutton said it was important to deepen military cooperation between the U.S. and Australia in order to deter "the most egregious forms of coercion and aggression."

The debate in Australia is framed in terms of protection of outraged sovereignty and the relentless urging of the U.S. to reciprocate with the same bellicose language that characterized the Donald Trump years.

To be sure, Biden is no good friend of China, and he has continued and enhanced many of the policy positions adopted by Trump. However, Biden is far more of a diplomatic realist than his predecessor or Australian Prime Minister.

It's useful to have attack dogs whose yapping serves to indicate how far things could go if they were let slip. The U.S., China and Australia all have these hard-line groups, but they serve to highlight the most extreme consequences should not be reached; instead, the governments should compromise.

The key use for these noisy proponents of conflict is the way they can be disowned as they are not part of formal policy. Their yapping serves to indicate how bad things could get, but restraining these elements serves to underline the sincerity of attempts to avoid the conflict and reach agreement.

However, current Australian foreign policy doesn't seem to comprehend. By its silence in the face of its parliamentary hard right-wing, the Australian government rather lends its tacit support to this yapping.

Biden's approach is different. He has the same hard anti-China group making media noises and given platforms on the right-wing media, but he is using this to effectively say "Look at how bad things could be if we don't reach a compromise and agreements."

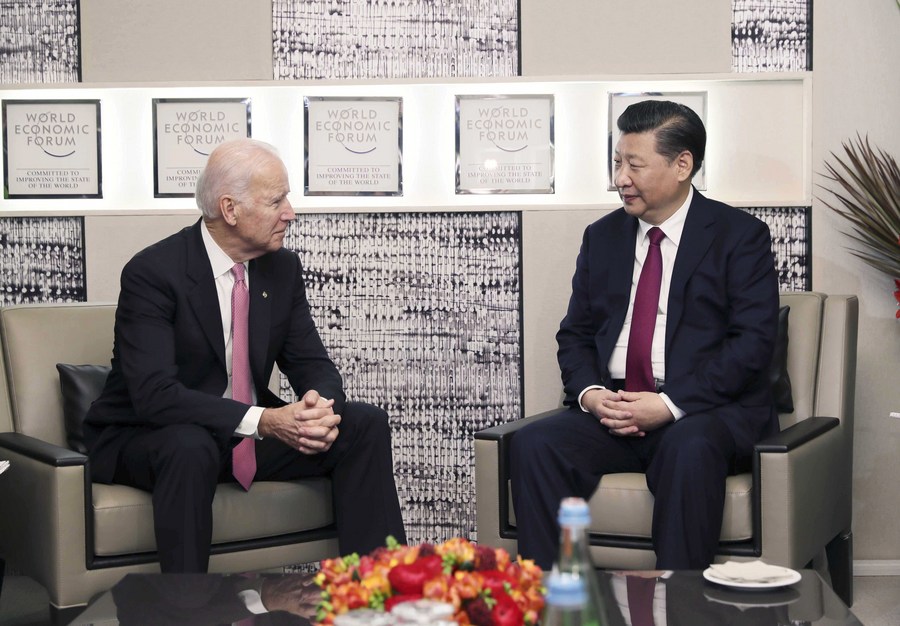

Chinese President Xi Jinping (R) meets then U.S. Vice President Joe Biden in Davos, Switzerland, January 17, 2017. /Xinhua

Chinese President Xi Jinping (R) meets then U.S. Vice President Joe Biden in Davos, Switzerland, January 17, 2017. /Xinhua

This is a subtle application of diplomacy that has been misread by Australia, which holds a deliberate misunderstanding of China and leaves itself to adopt a hard-line position that now appears not fully supported by its ally.

In 2020, Australian media and politicians challenged China to detail its areas of concern in the Australia-China relationship. China offered a list of 14 issues of dispute. Former Australian ambassador to China Geoff Raby explains that in diplomatic terms this is an aide-memoire – a note to assist one side or the other to recall matters discussed.

The Australian media and politicians seized on this aide-memoire, labeling it incorrectly as a list of 14 demands by China and a threat to Australian sovereignty.

Undeterred by the nuances of diplomacy, the Australian government continued with the deception that this was an attack on sovereignty and used this to increase pressure on China.

However, as Biden's phone call has shown, the U.S. has made a change in its perspective, and Australia is in danger of being "left in the lurch" by its most important ally. It's now a path out of step with Biden's more sophisticated approach.

But it remains to be seen if Australia has the diplomatic skill to extricate itself from the embarrassment of Biden's change in tone. "All the way with LBJ" was Australian Prime Minister Holt's cry in 1966 when U.S. President Lyndon Baines Johnson visited Australia. Perhaps "blind-sided by Biden" is now more appropriate.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)