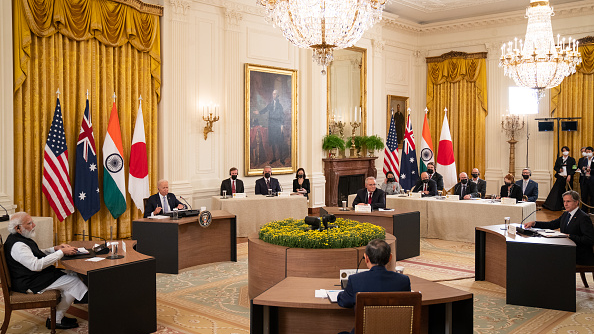

U.S. President Joe Biden hosts a meeting with Indian PM Narendra Modi, Japanese PM Yoshihide Suga, Australian PM Scott Morrison and U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken in the East Room of the White House in Washington, D.C., U.S., September 24, 2021. /Getty

U.S. President Joe Biden hosts a meeting with Indian PM Narendra Modi, Japanese PM Yoshihide Suga, Australian PM Scott Morrison and U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken in the East Room of the White House in Washington, D.C., U.S., September 24, 2021. /Getty

Editor's note: Yuan Sha is an assistant research fellow at the Department of American Studies, China Institute of International Studies. A former Fulbright scholar at Columbia University, she has a PhD in International Politics from China Foreign Affairs University. Yuan has published several papers on China-U.S. security relations in Chinese academic journals and is a regular contributor to many Chinese media outlets. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

The leaders from United States, Japan, India and Australia convened the first-ever-in-person Quad summit on September 24. Born out of humanitarian cooperation on the Indonesian tsunami in 2004, the quadrilateral partnership seemed innocuous at first. But over the years, it has become a geopolitical weapon for the U.S. to prolong its hegemony in the Asia Pacific region. But given the divergences of interests and values among partners, it is doubtful what the Quad can deliver as it promises.

What can be delivered

The joint statement released after the summit touched on a variety of hot topics of the day. They ranged from global issues such as the COVID-19 pandemic, infrastructure, climate change and critical technologies to regional issues such as Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Korea and the East and South China Seas. It also announced a spate of new initiatives, including a new Quad infrastructure partnership, a semiconductor supply chain initiative and a Quad Fellowship on Science, technology, engineering and mathematics studies.

But instead of focusing on what it said, it is equally important to see what is actually deliverable. For example, the much-hyped semiconductor supply chain partnership might require chip-making countries, i.e., the U.S. and Japan, to share the critical technology with other partners.

But given the "national security" status of the critical technologies, it is doubtful that meaningful cooperation would result. In fact, the joint statement reiterated the goal of building "habits of cooperation," which revealed the modest outcomes of the summit than anticipated.

More importantly, the Quad is not a formal alliance; its relevance is still in debate. As an adherent of the non-alignment movement, India has been hesitant to join a quasi-alliance with the U.S. Meanwhile, Japan is rejecting the notion of the Quad turning into NATO for Asia. It is also not wise for Australia to blindly bandwagon on the U.S. confrontation with other Pacific powers. Furthermore, the new trilateral AUKUS security partnership among the U.S., UK and Australia seems to be undercutting the Quad's influence.

Quad value cast into doubt

Aside from the question of relevancy, the Quad is running into a confidence crisis: "democratic value."

A health worker takes swab sample from a woman to test for COVID-19 at a vaccination center in Guwahati, India, June 7, 2021. /Getty

A health worker takes swab sample from a woman to test for COVID-19 at a vaccination center in Guwahati, India, June 7, 2021. /Getty

Their moral weakness to act as policemen of the Pacific is fully exposed during the past tumultuous year. The Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been criticized for mishandling the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to horrific scenes of open-air cremations on Indian streets.

The outgoing Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga is facing questions of staking his political future on hosting the Tokyo Olympics while neglecting the raging pandemic. Australian Prime Minister Scott Morison is raising alarms at home and abroad for his rash decision to acquire nuclear-powered submarines. U.S. President Biden is also afflicted with the disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan and the killing of Afghan civilians in the aftermath.

One would not help but wonder how well the Quad fulfilled its promise at the March virtual summit. After all, the Quad partners looked the other way when India grappled with a deadly outbreak of the pandemic in spring 2020, and the U.S. vaccine nationalism is exacerbating the global vaccine divide, which makes the Quad's vaccine partnership sound hypocritical.

A creature out of the cold war mentality

Despite President Biden's solemn declaration not to seek a new cold war at the United Nations General Assembly, the Quad regime is nothing but an anachronistic creature out of the cold war mentality.

Instead of an "inclusive and resilient" partnership for a "free and open Indo-Pacific," the Quad is an exclusive and increasingly rigid bloc, which is artificially erecting a 21st-century iron curtain. The confrontational stance and policies are making the region less free, less open and less stable.

By hijacking the term of multilateralism, the Quad is actually practicing "pseudo-multilateralism" among a select few countries in the attempt to contain China, the elephant in the room. The four countries do not represent the Asia Pacific, which is a diverse and dynamic region home to countries with various cultures, political systems and levels of socioeconomic development.

Most disturbingly, the regime is becoming increasingly militaristic, with the Quad members flexing muscles with joint military exercises and weapons transfer. The misgivings of neighboring countries toward the Quad are warranted, as these dangerous moves would unleash the hawkish tendencies, incur an arms race and miscalculations in the region.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)