South Korean protesters hold up a banner during a rally against the visit of U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin outside the Foreign Ministry in Seoul, March 18, 2021. /CFP

South Korean protesters hold up a banner during a rally against the visit of U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin outside the Foreign Ministry in Seoul, March 18, 2021. /CFP

After the fallout from Afghanistan rattled U.S. allies around the world, South Korea is looked upon as a success story of America's foreign wars.

"Technically, our longest war is not Afghanistan: It is Korea," wrote former U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice in a Washington Post op-ed in August. Rice noted that after several decades, the U.S.-South Korea security alliance has afforded Washington a valuable ally and "a strong presence in the Indo-Pacific."

Seventy years after the 1950-1953 Korean War ended in a stalemate, about 28,500 U.S. troops are still in South Korea to defend the country from the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK). The U.S. Forces Korea (USFK) is the third largest U.S. military presence outside continental United States after Japan and Germany.

As the Biden administration set out to restore alliances around the world and return as a leader in Asia Pacific, the USFK is expected to fit into a broader Indo-Pacific strategy that's centered on containing China's rise in the region.

However, the alliance has already been tested since previous U.S. President Donald Trump demanded a stunning five-fold increase in payments from Seoul for U.S. troops stationed in the country. According to a new agreement between the two countries announced in March, South Korea will pay 14 percent more in 2021 to host U.S. troops.

Opponents have protested that it is the U.S. that should pay South Korea to keep using its land for American soldiers, and that the USFK is a symbol of the Cold War, which ended a long time ago.

But long before the cost-sharing row, popular discontent over the U.S. presence in South Korea has always been brewing in the background.

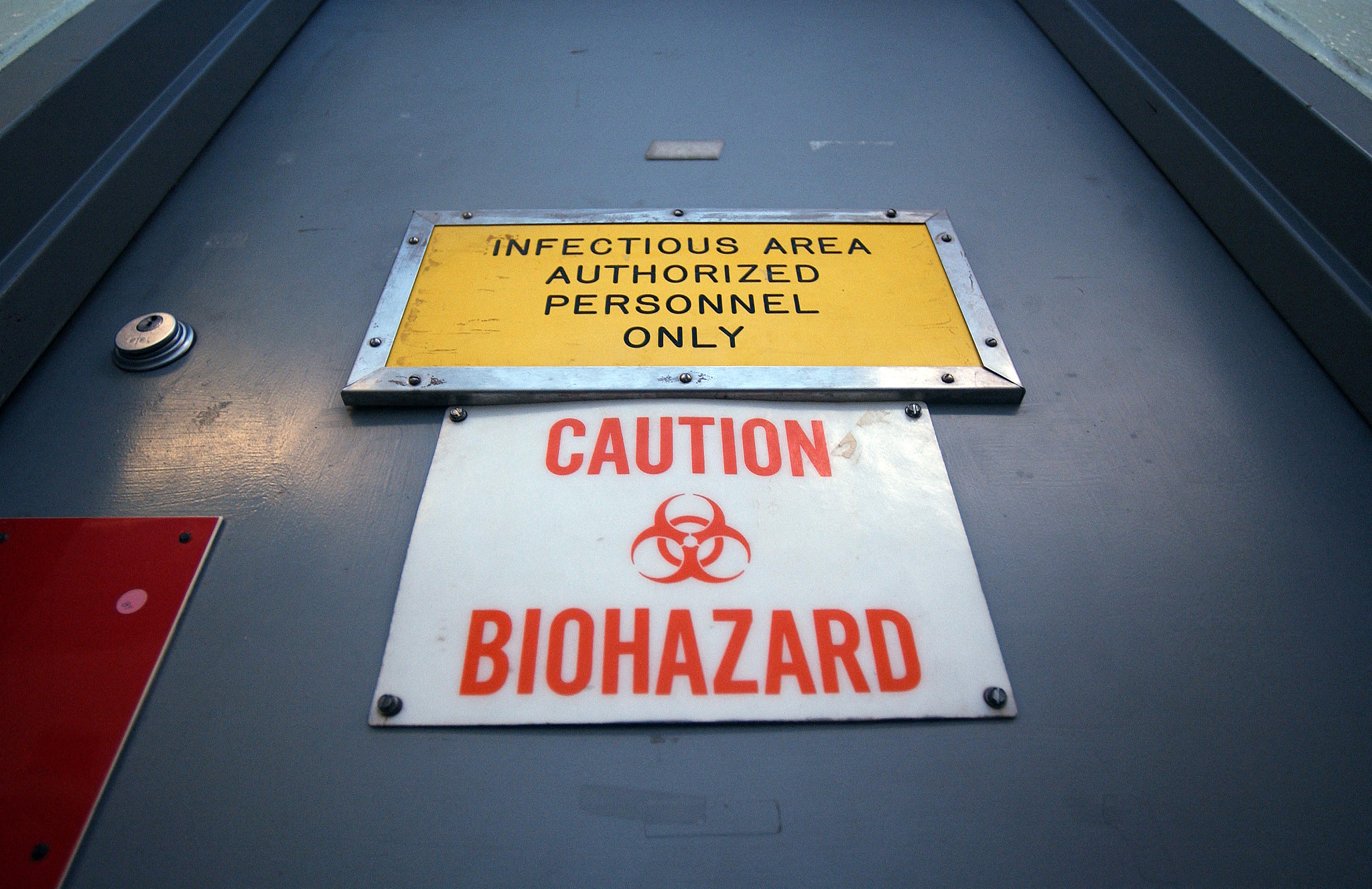

In August, a South Korean civic group sued the Fort Detrick biological laboratory in Maryland and the USFK for smuggling lethal toxic substances to U.S. military bases in the country between 2017 and 2019. The complaint claimed that the U.S. army imported anthrax samples against South Korean laws and conducted secret experiments which endangered local residents.

The bio-level 3 and 4 lab at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick, Maryland, September 26, 2002. /CFP

The bio-level 3 and 4 lab at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick, Maryland, September 26, 2002. /CFP

A previous investigation in 2015 found that the USFK had staged 15 experiments using dead anthrax samples at the Yongsan Garrison in Seoul from 2009 to 2014. It was also revealed that the U.S. army brought specimens of plague bacillus into the country.

The new lawsuit is only the latest in a long history of grievances against the USFK.

Crimes, impunity and institutionalized prostitution

A mutual defense treaty signed in 1953 provided the basis for U.S. forces stationing in the Republic of Korea (ROK). Then in 1966, the two countries signed the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) to lay down the rules governing U.S. personnel in South Korea.

Until the SOFA came into force in 1967, South Korea had no jurisdiction at all over crimes committed by U.S. soldiers in the country. In that year alone, 1,710 criminal cases were recorded, of which South Korea exercised jurisdiction in only nine that were considered serious offences.

South Korean authorities were powerless in dealing with U.S. crimes and the exercise of jurisdiction was less than one percent, activists say.

According to the National Campaign for the Eradication of Crimes by U.S. Troops in (South) Korea, a citizen group started in the 1990s to monitor U.S. crimes in South Korea, U.S. troops have committed tens of thousands of crimes against South Korean civilians since the beginning of its military occupation in 1945.

A collision between a U.S. military vehicle and a private car killed four civilians in Pocheon, Gyeonggi Province, South Korea, August 30, 2020. /CFP

A collision between a U.S. military vehicle and a private car killed four civilians in Pocheon, Gyeonggi Province, South Korea, August 30, 2020. /CFP

"The perception among many here is that U.S. soldiers commit crimes and then run back to the protection of their base," said Park Kyung-soo, director of the watchdog group, which was formed after the gruesome murder of a 27-year-old local woman by a U.S. soldier in 1992 shocked the country.

As a result, South Korea's civil society has long perceived the relationship with the U.S. as profoundly unequal. In the 2000s, an ugly episode in the history of Washington-Seoul security alliance came to light.

Between the end of the Korean War and the early 1990s, more than one million South Korean women were caught up in a sex industry catered exclusively for U.S. troops in so-called "camptowns."

According to various media reports, vulnerable women were encouraged by their government to sell themselves to U.S. soldiers in order to strengthen the alliance after the armistice. Due to the scale of the practice and disease fears, the U.S. military even ran special facilities where sex workers were forced to undergo medical treatments and quarantines until they were healthy enough to work again.

Since the mid-1990s, South Korea's economic boom has largely allowed local women to escape the exploitation of the camptowns, where abuses of sex workers or other civilians by U.S. service members usually went unreported or unpunished. But their old roles were then filled by migrants from other parts of Asia, making U.S. bases in South Korea "a hub for the transnational trafficking of women," researchers concluded in 2007.

How South Korea sees U.S. today

Anti-American sentiment has always existed in South Korea. But before the 1970s, the country was not in a position to say no to the U.S. because it depended on U.S. military for security, and those who spoke up were silenced, Shi Hong, executive editor-in-chief of naval magazine Shipborne Weapons told CGTN.

From 1980, however, resentment toward the U.S. has escalated in the country. The turning point was the bloody crackdown of popular protests in Gwangju by the military government of general Chun Doo-hwan. The protesters had hoped for U.S. support, only to find out that Chun's order to use force was backed by the Carter administration.

The incident shook the very foundations of America's Cold War power structure in Asia. According to Dr. So Jun-seop, an expert at the National Assembly Library who was jailed after the Gwangju crackdown, anti-dictatorship and anti-Americanism were closely intertwined throughout the 1980s.

In 1987, then U.S. ambassador to the ROK Richard Walker handed an urgent 10-page memorandum to his successor James Lilley to warn of a rise in anti-American sentiment.

"There are mainly three types of anti-American South Koreans: the leftists who are ideologically anti-American, the nationalists against what they see as U.S. occupation, and those who are angry with the U.S. on specific issues," Shi told CGTN. "The anti-American generation of the 1980s are the backbones of South Korean society today."

After the Cold War, South Korea has seen its overall strengths growing by leaps and bounds compared to the DPRK, another important reason for the country's changed attitude toward the U.S., Shi added.

Scuffles break out between police and local residents outside the U.S. Forces Korea's THAAD base in Seongju as protesters try to block shipments of equipment into the base, South Korea, February 25, 2021. /CFP

Scuffles break out between police and local residents outside the U.S. Forces Korea's THAAD base in Seongju as protesters try to block shipments of equipment into the base, South Korea, February 25, 2021. /CFP

Contrary to common belief, the U.S. presence in South Korea today is hardly viewed as safeguarding Seoul's democratic values as opposed to those of Pyeongyang.

The view propagated by some Western media that Asian countries which share the same political ideology with the U.S. need its military protection is just one-sided wishful thinking, Shi said.

"Washington needs allies in the Indo-Pacific to assist in its geopolitical ambition, but it also wants them to help foot the bills and alleviate its fiscal burden," Shi said. "Most countries in the region understand what the U.S. is trying to do, and few want to be a pawn in its competition with China."

"Therefore, countries like South Korea and those in ASEAN did not get on board [with the alliance against China]," he said. "Because most countries and regions in the world seek peace and development, not more tensions on their doorsteps."