Editor's note: This is a four-episode series that dives into the four time periods that were turning points in China's modern history: the New Democratic Revolution from 1919 to 1949; the Socialist Revolution in the 1950s; the Reform and Opening-Up since 1978, and the New Era of socialism with Chinese characteristics post 2012. The second episode focuses on the Socialist Revolution, through which China industrialized rapidly. You may find the first, third and fourth episode here.

Daqing oil field, 1960. A blowout just occurred at the second well. Wang Jinxi, a model worker and the captain of a drilling team, tossed away his crutches, plunged into the mud pool on one leg as he hurried others to keep pouring cement into the pool. He stirred vigorously, using his own body as a mixer to increase the mud weight, getting it ready to be used to stop the accident. Inspired by their captain, several workers soon joined in. After a three-hour battle, the blowout was subdued. That night, Wang went home with the nickname of "iron man," and a body full of blisters from cement burns.

Wang Jinxi, a model worker in the Daqing oilfield, is stirring in a mud pool to get the mud ready for use to stop a blowout accident, in Daqing, Heilongjiang Province, northeast China. /Public Domain

Wang Jinxi, a model worker in the Daqing oilfield, is stirring in a mud pool to get the mud ready for use to stop a blowout accident, in Daqing, Heilongjiang Province, northeast China. /Public Domain

Wang was just one of the millions of Chinese workers who gave their all on their posts during the decade of nation-building. After emerging victorious in the civil war, the Communist Party of China's (CPC) new task was to lead the people in building a new China. To Chairman Mao Zedong, China's revolution must go through two stages: first, the New Democratic Revolution – the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC) marked its completion; second, the Socialist Revolution, the goals of which included public ownership of the means of production and elimination of exploitation, thus "making the people masters of the country."

"To win countrywide victory is only the first step in a long march of 10,000 li (a traditional Chinese unit of distance) ... We are not only good at destroying the old world, we are also good at building the new," Mao said in early 1949, when the victory of the War of Liberation was almost in hand.

The new China, however, faced a series of challenges. The war-stricken country had scarcely caught a break in the previous 100 years. By the establishment of the People's Republic in 1949, China had just endured a full-scale civil war, and right before that, 14 years of atrocities committed by Japanese invaders. The country's economy was on the brink of collapse: mines and factories were destroyed; transportation and power systems had lacked maintenance for years; most importantly, agriculture, what China had lived upon since ancient times, had been severely damaged by wars and natural hazards. According to the State Archives Administration, the total grain output in 1949 was 225.47 billion jin (112.74 million tonnes), 21 percent lower than its pre-war peak of 284.46 billion jin (142.23 million tonnes) in 1936.

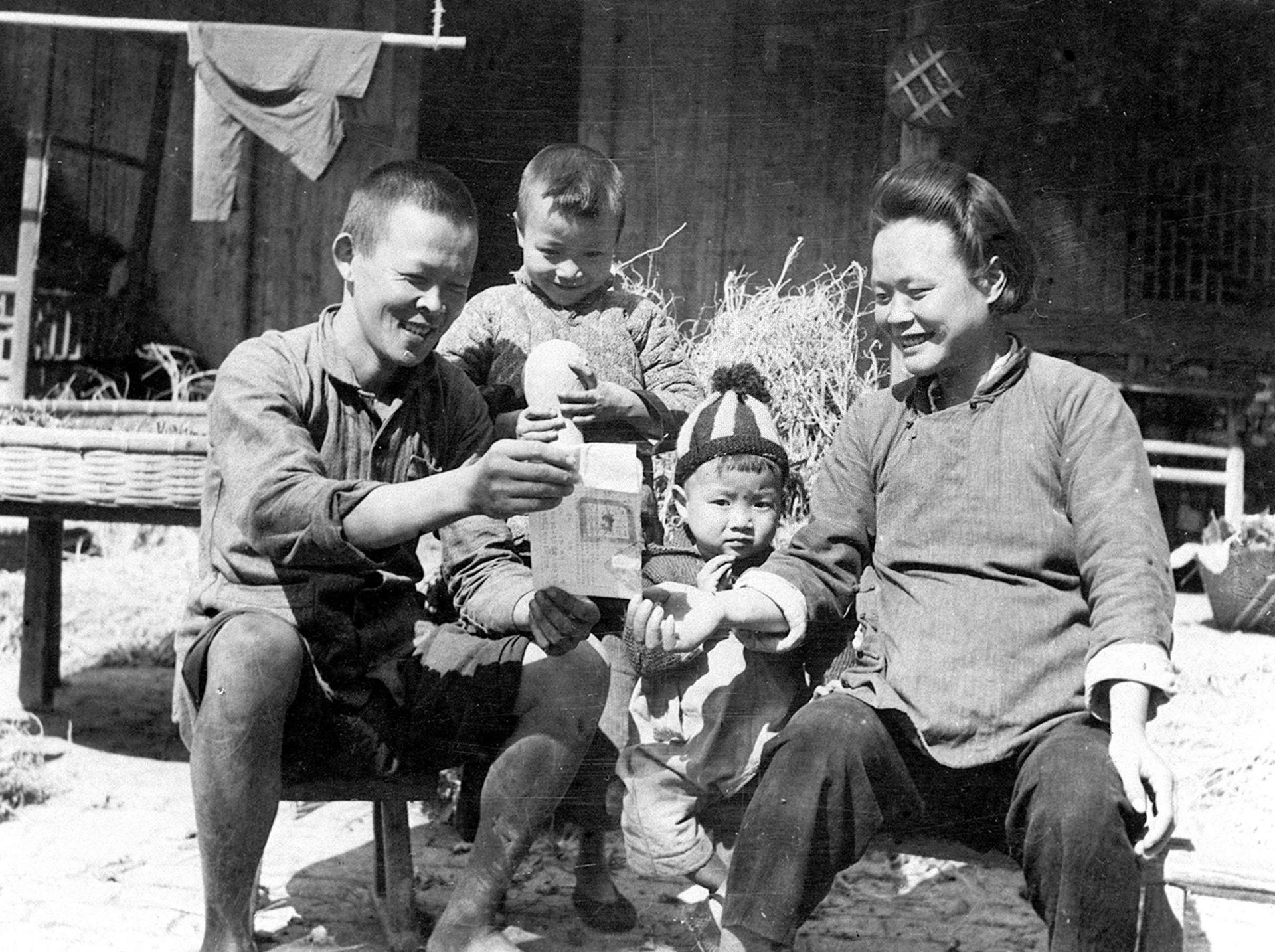

To tackle this problem, the CPC implemented a series of policies to quickly restore the economy back to order. The railway network expanded, and the destroyed tracks were repaired. The People's Bank of China was established to maintain financial stability, and most state revenue was centralized under state control. The renminbi was also issued to unify the currencies. Additionally, land reform redistributed the ownership of the country's farmland. Peasants who worked for landlords now had their own land. By the end of 1952, around 300 million landless peasants received 46.66 million hectares of arable land.

A peasant family receives their land certificate in Jiaxing, Zhejiang Province, east China, 1950. /Xinhua

A peasant family receives their land certificate in Jiaxing, Zhejiang Province, east China, 1950. /Xinhua

Wang was a witness to the changes. In 1923, he was born into a poor peasant family in northwest China's Yumen County. At 6, the boy was begging on the street while leading his blind father with a stick. By 10, he was herding cattle for landlords, saving money for his father's treatment. Then at 12, he turned to child labor. In September 1949, Yumen was liberated. The landlord who used to whip him was stripped of his lands, which were distributed to peasant families like Wang's. A few years later, he joined the Communist Party.

In 1953, the CPC carried out its first Five-Year Plan, an economic program to concentrate on industrialization, and heavy industry was accorded a top priority.

"What can we make at present? We can make tables and chairs, teacups and teapots, we can grow grain and grind it into flour, and we can make paper. But we can't make a single motor car, plane, tank or tractor," Mao said at the 30th Session of the Central People's Government Council in 1954.

Petroleum was among the resources that China lacked most. The country was estimated by foreign geologists to be barren of oil resources, and it had relied on buying oil from the Soviet Union to fill the huge demand gap.

In 1950, Wang became one of the first generation of oil workers in the PRC. Years of hard work honed his skills, and in 1958, he led his team to a national drilling record of 5,009 meters per month, which earned him the honor of "national model worker." In 1959, he and other model workers were invited to Beijing to meet with Chairman Mao in person.

A story of Wang's visit in Beijing remains to this day. First time in a major city, a strange sight intrigued the countryman: every bus he saw carried a gigantic bag on top. He soon learned from the locals that those were coal gas bags used as an alternative way to fuel the bus due to the nation's serious lack of petroleum. Wang was dumbfounded. Despite his team drilling tonnes back in Yumen, the rest of the nation, even the capital, still suffered a shortage, and he was totally unaware.

A gas bag bus in China. /Public Domain

A gas bag bus in China. /Public Domain

In 1960, news spread that a new oil field, and potentially the richest oil field in China, had been discovered. Wang volunteered as a leading trail blazer for this new expedition. The team of thousands of workers embarked on their journey with no proper equipment, and marched on the rugged roads into the punishing cold in northeast China. At the inauguration ceremony of the new-found oil field, named Daqing – meaning "big celebration" – Wang shouted: "I will fight tooth and nail to conquer the oil field, even if living 20 years less!"

By 1963, China was completely self-sufficient in petroleum supply, the days of relying on imported oil were gone. Today, the Daqing oil field still remains the largest oil field in China, producing more than 40 million tonnes of crude oil a year.

"I'm an ordinary worker. Got no talents, only just drilled a few wells for the country. All my honors should go to the Party and the people," reads one page of Wang's notebook, which is exhibited at the Iron Man Wang Jinxi Memorial.

In 1970, Wang succumbed to stomach cancer. He was 47 years old. The "Iron Man's" legacy lives on, as his story has inspired generations of oil workers to this day.

The statue of Wang Jinxi at the Iron Man Wang Jinxi Memorial in Daqing City, northeast China's Heilongjiang Province. /Xinhua

The statue of Wang Jinxi at the Iron Man Wang Jinxi Memorial in Daqing City, northeast China's Heilongjiang Province. /Xinhua