04:43

Squeezing into a packed subway train is a familiar experience for most city dwellers in China.

The country is home to five megacities, each of which has a population of over 10 million people. Although many have gotten used to the close physical proximity on subways, overcrowded carriages are all too often not a safe space for passengers.

Several years ago, while Wang Xin was riding the subway in Beijing, she felt a hand touching her inner thigh. When she turned her head to look, her suspicion immediately fell on a thin-framed man with glasses. But she couldn't be sure.

"It was unlikely that he did that unintentionally," said Wang. "But I chose to be silent because I was about to get off the train," she recalled with disgust.

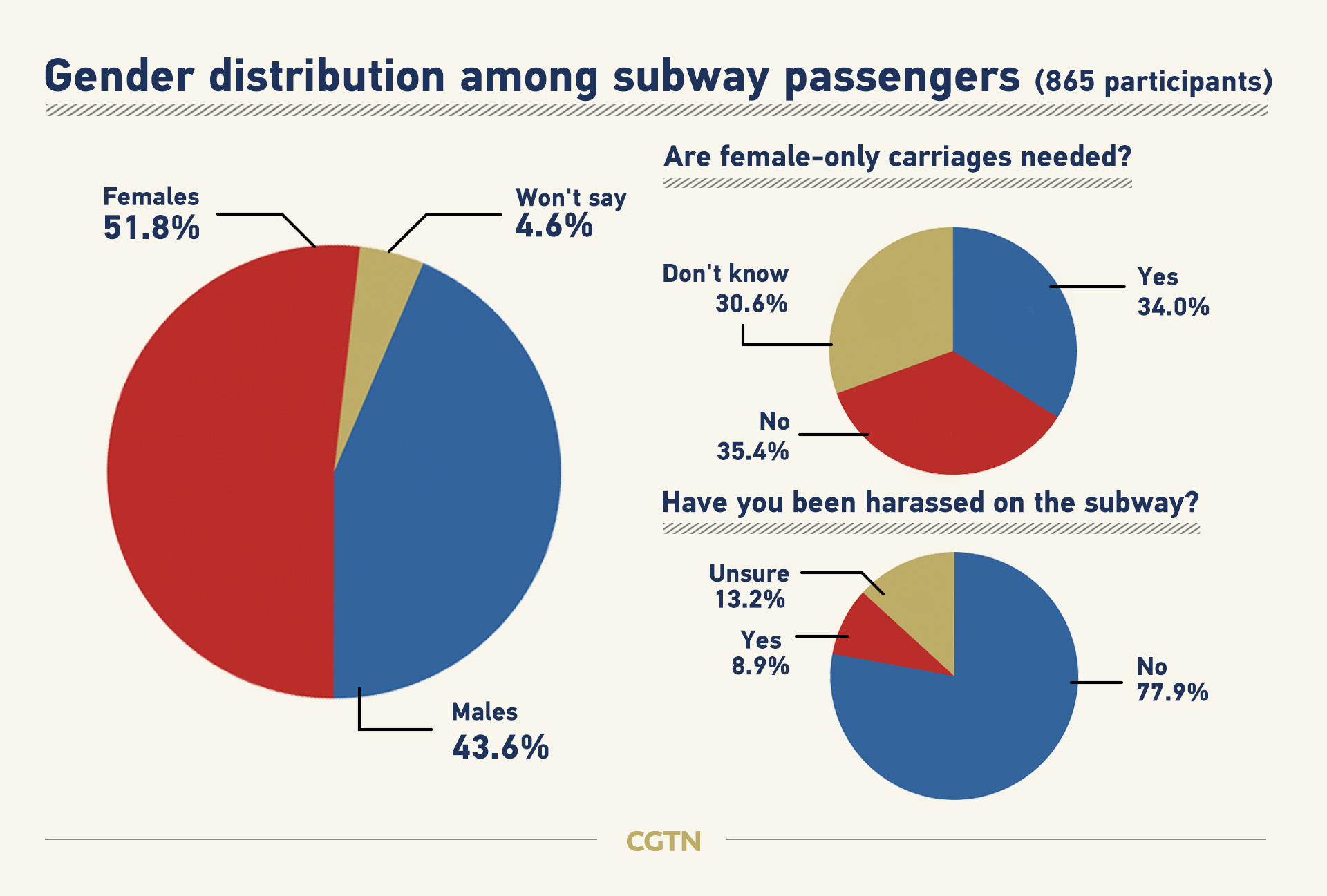

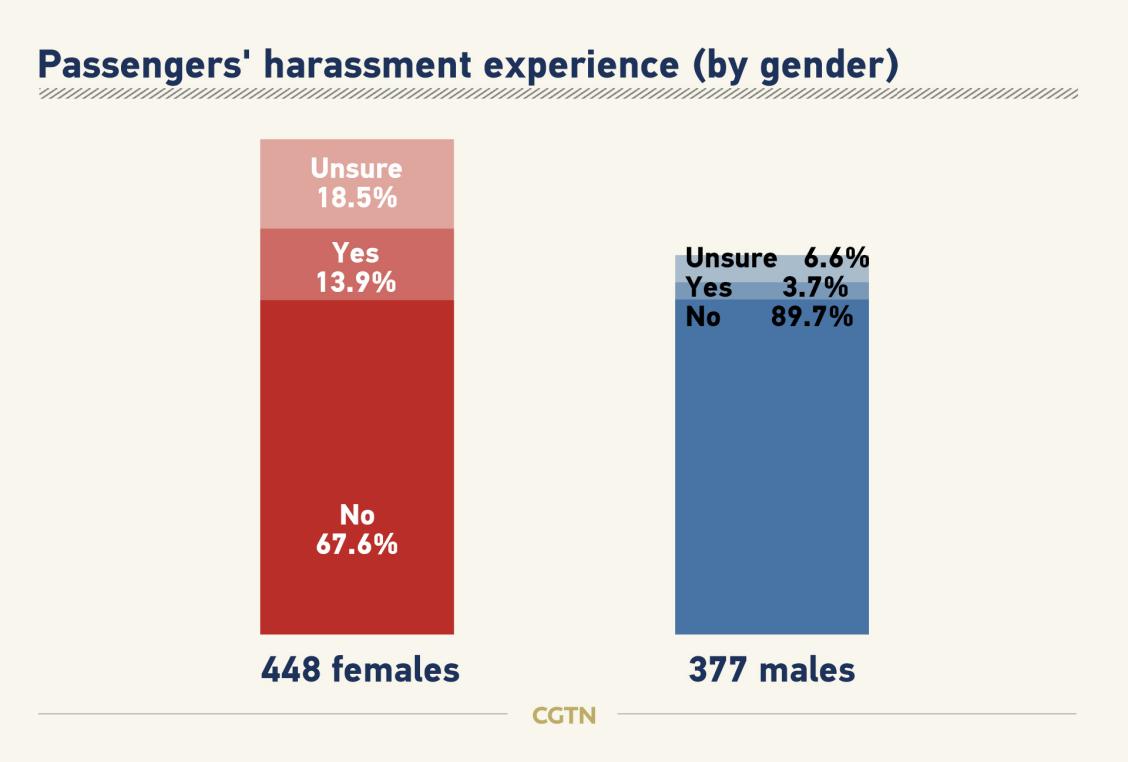

An online poll carried out by CGTN in August on WeChat, China's largest message app, showed that nearly nine percent of all 865 respondents from China had experienced harassment on the subway, and more than 13 percent were not sure whether their uncomfortable experience could be counted as harassment. Among female participants, almost 14 percent believed they had been harassed, compared with about four percent of male participants.

The survey also showed that roughly 65 percent of all respondents supported female-only carriages or would like to give them a try. Among those supporters, nearly 64 percent were female. Women are more likely to fall victim to harassment, but whether female-only carriages would help remains a hotly debated question in China and beyond.

"Personally, I wouldn't bother myself finding the carriage for ladies during peak hours," said a 30-year-old woman living in Guangzhou. The city set up female-only carriages since 2017 along with Shenzhen, another big metropolis in south China's Guangdong Province.

Zhengzhou, capital city of central China's Henan Province, joined in on the act last December. While some supporters argue female-only carriages can prevent sexual harassment and create a better environment for women, others say they are impractical during rush hours, as there aren't nearly enough for all female passengers.

Women wait for a carriage for ladies at Gongyuanqian metro station in Guangzhou, capital of south China's Guangdong Province, June 28, 2017. /VCG

Women wait for a carriage for ladies at Gongyuanqian metro station in Guangzhou, capital of south China's Guangdong Province, June 28, 2017. /VCG

When female-only carriages were introduced in Japan in 2000, they quickly received widespread support, especially among passengers who are afraid of "chikan," usually referring to sexual predators who take advantage of crowded spaces on public transport.

In Tokyo, over half of reported groping cases during 2020 occurred on a train or at a station.

Female passengers in a women-only carriage of a subway train which is to leave Shinjuku station in Tokyo, Japan. /AFP

Female passengers in a women-only carriage of a subway train which is to leave Shinjuku station in Tokyo, Japan. /AFP

Back in 2009, India introduced eight "ladies special" trains reserved entirely for female passengers in major cities including Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata and Chennai. They gained popularity among women and the practice became a source of pride for local subway operators.

Many pointed out that the ultimate solution to reducing sexual harassment against women on public transport is to educate people including children to respect women and offer help when needed.

A "ladies special" train in Mumbai, India. /Reuters

A "ladies special" train in Mumbai, India. /Reuters

Though popular in Asia, similar measures were criticized in the UK and Germany by some who said segregating women in public was a backward solution. Efforts to protect women from sexual harassment on public transport cannot rely solely on designated spaces as its effectiveness varies across different regions and cultures, they argue.

Beyond the special space

Several cities in France and Brazil have embraced public awareness campaigns to reframe the transit safety problem for women. Posters on trains, buses and social media platforms call for more awareness of sexual harassment in public transportation.

A Beijing Women's Federation's public service advertisement for preventing sexual harassment is placed in all subway cars in Beijing Subway Line 10, Beijing, China, August 20, 2018. /VCG

A Beijing Women's Federation's public service advertisement for preventing sexual harassment is placed in all subway cars in Beijing Subway Line 10, Beijing, China, August 20, 2018. /VCG

Since 2017, the Beijing Women's Federation, a branch of the All-Women's China Federation, has been using posters and videos to deter offenders and educate the public on sexual harassment and its prevention.

Technology is joining the campaign by facilitating reporting and data collection. In Tokyo, the "Digi Police" smartphone app developed by the Tokyo Metropolitan Police has been downloaded hundreds of thousands of times. Users can activate the app that blasts off "stop it" repeatedly to deter gropers. The app can also produce a full-screen SOS message reading: "There is a molester. Please help."

In 2017, Los Angeles County launched a 24-hour hotline to make trains or buses safer. Different from the sexual assault hotline, callers could have a direct link to metro security for reporting and tracking the assaults, and are also offered follow-up services such as psychological counseling.

A subway train, Beijing, China. /VCG

A subway train, Beijing, China. /VCG

Since 2017, the Beijing Subway has worked in concert with local police forces to carry out a pervert-hunting campaign, which involves training patrol officers and metro staff to collect evidence and seize suspects.

"I will report to the station police immediately if I am informed by the security staff in the carriages. The police officers will arrive within minutes," said a metro staff attendant of Line 1 at the Guomao station in Beijing.

Video: Global Stringer, Liu Hangjian

Video editors: Yang Yiren, Zhong Xia

Infographics: Li Jingjie

Cover image designers: Yu Peng, Li Jingjie

Editor: Zeng Ziyi