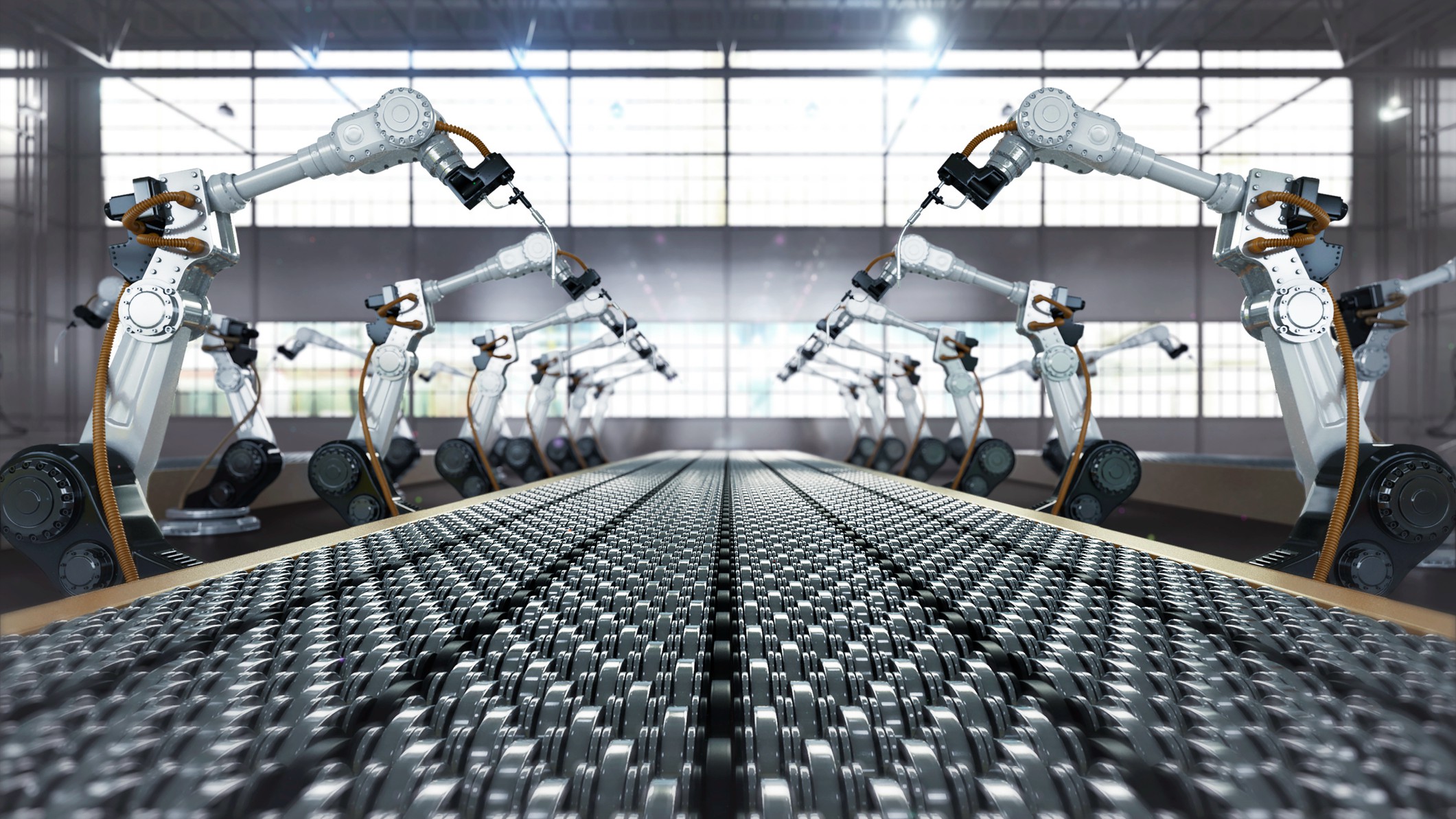

Robotic arm and steel conveyor in assembly manufacturing factory. /Getty

Robotic arm and steel conveyor in assembly manufacturing factory. /Getty

Editor's note: Nichol Bradford is co-founder and executive director of Transformative Technology Labs. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily those of CGTN.

Automation is already destroying millions of jobs. It is also creating them. Employees and bosses have to prepare for a workplace that doesn't yet exist. As the fourth industrial revolution threatens to automate whole industries and upend the world of work, we need to understand what skills we do, and don't need, so our economies and societies can come through it stronger.

The unique human abilities of creativity, collaboration and communication will be in high demand – they can't be automated – so we need to be prioritizing them today. The booming industry of transformative technology, or technology that improves humans' mental health and cognition, could provide the answer we need to take this next step.

Technology has already transformed the world around us; it's time to allow it to transform us as individuals too.

The fourth industrial revolution is set to eliminate the need for countless jobs we pay people to do today. Cars will be able to drive themselves, machines will be able to read and understand X-rays and algorithms will be able to helpfully respond to customer service requests. Articles like this one could be drafted – if not written and edited – by machines (The Guardian proved this last year).

Automation is creating challenges for employers and policymakers alike. Mckinsey had previously predicted that 45 percent of the activities that people are paid to perform could be automated. According to BBC analysis, there is a 50 percent chance that machines could take over all human jobs over the next 120 years.

This will present us with a huge problem as unemployment increases. Look at truck drivers in the U.S. as an example. There are approximately 3.5 million professional truck drivers in the U.S. today, and the wider industry, from roadside cafes to tyre repair, employs about 8.7 million people. The industry faces a crisis; the Los Angeles Times has reported that driverless trucks could replace up to 1.7 million jobs in the next decade.

The knock-on impact would be enormous. The average age of a trucker in the U.S. is 47; simply retraining in another skill at a later age, with the responsibilities of families and mortgages, may prove impossible for many.

Sudden mass unemployment would cause drug addiction, crime and homelessness to skyrocket. We need to make sure that automation works for humans and not against them; we need to manage this transition carefully.

Truck drivers are just an example. Automation is coming for the lowest skilled jobs first, but it won't end there. If we're not careful, this could exacerbate inequalities that exist across class and racial lines. In the UK, people of color are far more likely to be over-represented in lower-skilled, lower-paid work like taxi driving or service work.

We've seen this labor transition before; during the industrial revolution of the 19th, a group of radical English textile workers conspired to break machinery they deemed would threaten their livelihoods. They were referred to as Luddites, which in modern times has come to be a derogatory word for anyone who dislikes new technology.

A package on the conveyor belt gets its label at Amazon fulfillment center in Eastvale, August 31, 2021. /Getty

A package on the conveyor belt gets its label at Amazon fulfillment center in Eastvale, August 31, 2021. /Getty

Whilst their methods were unsavory, their premonitions were prescient. New technologies do steal jobs, but that's only if we're not prepared. The invention of the factory, tractor and loom did not permanently increase unemployment; labor just redistributed.

Millions entered the middle class and sought employment in administration, law, finance and medicine; in other words, former factory employees sought knowledge work. The same needs to happen today.

The skills that will be highest in demand will require a "monkey in the machine," i.e., human involvement. When software can do the rest, industries will be reliant upon the human skills of cognitive flexibility, collaboration, creativity and empathy. These are the skills that I refer to as "deep human." We need more of them.

The secret to preparing our workforce for this brave new world lies in "transformative technology": hardware- and software-based tools designed to enhance human psychological well-being, cognitive function and physical capabilities.

We're used to using technology to shape the outside world. Today, there is a renaissance in technology that could also transform our inner psychological landscapes. These technologies can help us to work better as a team, choose jobs that are a better fit for us, as well as enhance our creative problem-solving abilities.

For example, the startup Levell helps employees register their moods and establish how they work best together. Another example is Skillprint, which offers games that help employees discover their working strengths and weaknesses, and identify the roles that best match their psychological make-up.

Kernel has developed a helmet that can record our brainwave activities with record-breaking precision, granting individuals insight into how their brains actually work.

We have successfully used technology to solve our greatest and most trivial needs, from vaccine development to pizza delivery. Whilst we have used technology to transform our outer worlds, I see no reason why we shouldn't use it to transform our inner lives.

If we do not prepare ourselves and our workplaces for the age of intelligent automation today, we risk facing huge demographic displacement in the coming decades. We cannot afford to be Luddites.

If we use these transformative technologies to create, connect and collaborate on a large scale, then the coming decades could be one of the most high-growth periods – at the economic and personal levels – that humanity has seen.

Our choice right now is between a machine-led dystopia or a human-led utopia. It is our job now to actively opt for the latter.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)