A line of cars stretching several blocks wait to pull into an appointment-only COVID-19 testing center in Seattle, U.S., January 6, 2022. /CFP

A line of cars stretching several blocks wait to pull into an appointment-only COVID-19 testing center in Seattle, U.S., January 6, 2022. /CFP

Editor's note: Li Yihao is a doctoral candidate in urban planning at Harvard University. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

For those of us who judge the state of the world through the vitality of our largest cities, the past two years have been particularly disappointing. The onslaught of the coronavirus – and our responses to it – has turned once-buzzing city streets and public spaces into ghost towns almost overnight.

In the United States, millions fled from big cities in 2020, sending house prices in suburban and rural areas through the roof. In India, road traffic leaving the cities was so bad that troves of migrant workers had to walk hundreds of kilometers to return to the perceived safety of their villages.

Even for those who remain, the quality of urban life can deteriorate quickly. Social distancing has turned neighbors into strangers, and waves of lockdowns have made urban life even harder. As people cut back on restaurant meals and gym workouts, businesses close, municipal tax revenues drop, public services like police and sanitation deteriorate, crimes rise, new businesses stay away, and more people leave. As the pandemic stretches into the third year, the specter of urban decay seems increasingly probable for some cities.

It is easy to blame urban density for our current public health woes. After all, for a highly infectious virus that transmits through the air, the very proximity that defines the city also enables mass contagion. We tend to think that if only people are more spread out spatially, fewer people will be infected. But is density really the culprit?

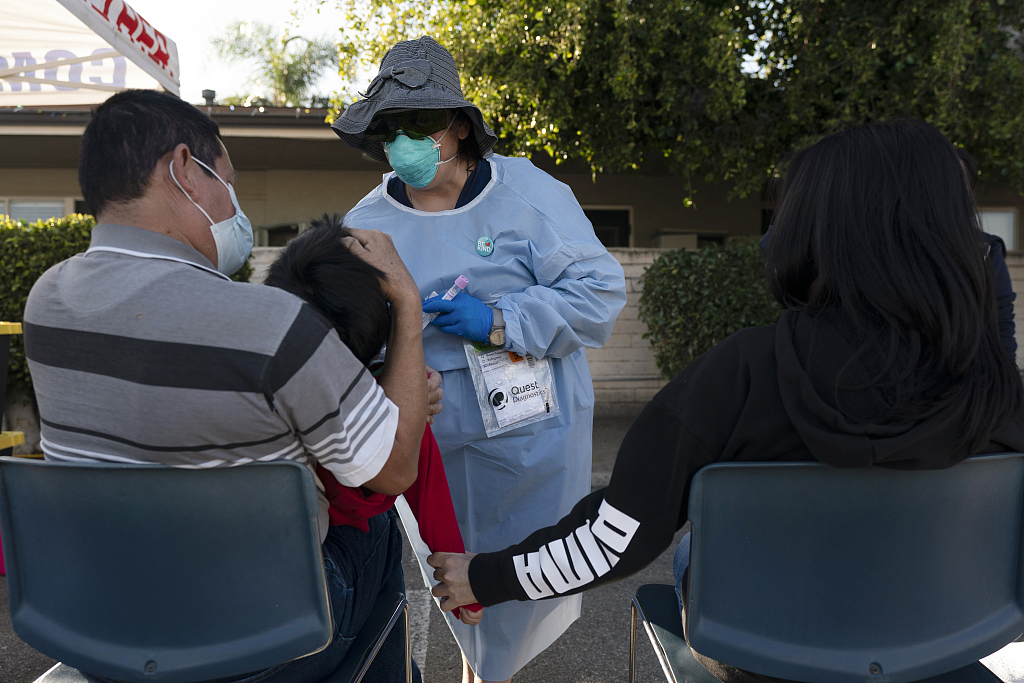

Nurse practitioner Rita Ray collects a nasal swab sample for a COVID-19 test at Families Together of Orange County community health center in Tustin, California, January 6, 2022. /CFP

Nurse practitioner Rita Ray collects a nasal swab sample for a COVID-19 test at Families Together of Orange County community health center in Tustin, California, January 6, 2022. /CFP

COVID-19 infection numbers in the United States offer some curious insights. If we break down U.S. COVID-19 infection and death numbers spatially, we find that on a per capita basis, COVID-19 cases in urban areas are in fact fewer than those in rural areas. In other words, contrary to popular assumption, a rural resident in the U.S. is more likely to be infected and die from COVID-19 than their urban counterpart. Many scientists attribute this discrepancy to the lower rates of mask-wearing and vaccination among American rural residents. Distance to hospitals also made it difficult to obtain COVID-19 tests and medical care.

It is increasingly clear that urban density per se is not the problem. The real issue is how density is managed. Dense cities such as Shanghai and Singapore have been successful at stamping out the virus in part because they used density to their advantage, namely, by being efficient.

Well-managed density allows public health authorities to detect COVID-19 cases early and quickly, because COVID-19 "alarm bells" can be built throughout the city – be it a testing site at every other street corner, a pharmacy that tracks customers that ask for fever-reducing drugs, or a temperature checkpoint at public places. Well-managed density also allows governments to inoculate many people quickly and cheaply.

Just as important, density makes the development of digital infrastructure commercially viable, which in turn enables the widespread use of contactless technology that has proven critical to both contact tracing and minimizing the disruptions to our daily lives.

A key lesson from the pandemic is that cities that best leverage the efficiency advantage of urban physical and digital infrastructure are better positioned to outrun the virus at every turn, while those that fail to do so risk urban decay.

Sadly, many factors prevent cities from making full use of the efficiency advantage. Some have delayed investment in critical infrastructure for too long, and others have become too bogged down by politics to make timely and pragmatic decisions. Across developed and developing countries, staggering inequality in healthcare access laid bare long-standing gaps in infrastructure provision, while the indiscriminate use of large-scale lockdowns exposes weak links in urban governance.

COVID-19 is not the first pandemic to hit cities, nor will it be the last. In the post-pandemic world, people will, once again, vote with their feet. Cities that controlled the virus without sinking the local economy will likely see an influx of people, capital and knowledge. In the longer term, those that effectively address their underlying vulnerabilities in infrastructure access and governance are better positioned to survive the next pandemic. Those that do not may wither away, leaving a long and messy trail of socio-economic dislocation in their wake.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)