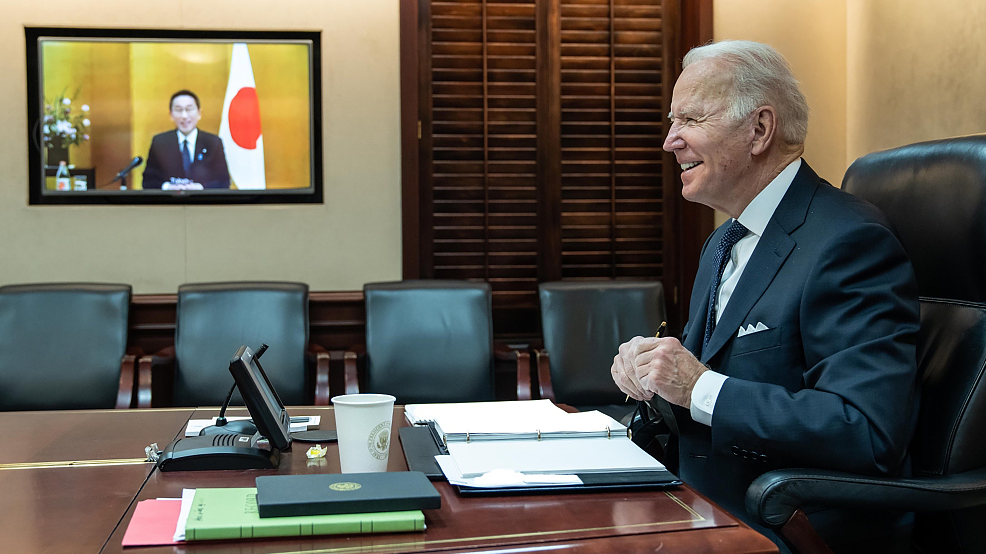

U.S. President Joe Biden meets virtually with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida in the Situation Room of the White House in Washington, D.C., January 21, 2022. /VCG

U.S. President Joe Biden meets virtually with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida in the Situation Room of the White House in Washington, D.C., January 21, 2022. /VCG

Editor's note: Hannan Hussain is a foreign affairs commentator and author. He is a Fulbright recipient at the University of Maryland, the U.S., and a former assistant researcher at Islamabad Policy Research Institute. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

On January 21, U.S. President Joe Biden and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida met virtually to mark their first meeting since Kishida took office. As expected, the veneer of a strong U.S.-Japan relationship didn't hold for long against a shared desire for regional interference. "The two leaders resolved to push back against the People's Republic of China (PRC)'s attempts to change the status quo in the East China Sea and South China Sea," stated a readout of the meeting.

Manufactured concerns in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, blatant disregard for China's territorial sovereignty over Diaoyu Islands, and more U.S.-Japan doublespeak on cross-strait relations serve as a reminder that such anti-China posturing will yield no fruit for Japan. That is because China's sovereign interests are unquestionably sovereign, and debating that reality – even in rhetoric – may signal to Asia that the U.S.-Japan alliance is not fit for peace.

It is Washington – not Beijing – that represents a credible threat to stability in the East and South China Seas. The U.S.'s support for unlawful maritime claims, its conscious efforts to sow discord between neighbors, its advancement of controversial Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs), and its treatment of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) as political leverage make it all very clear. In fact, these are the provocations that necessitate true "push back."

So does Tokyo's persistent attempt to acquire false assurances from Washington on the applicability of the Japan-U.S. security treaty to China's Diaoyu Islands. "The President [Biden] resolutely affirmed that Article V of the Mutual Security Treaty applies to the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu Islands), and affirmed the U.S.'s unwavering commitment to the defense of Japan, using its full range of capabilities," mentioned the readout.

Ships sail during the second phase of the Malabar naval exercise in which India, Australia, Japan and the U.S. are taking part in the Bay of Bengal in the Indian Ocean, October 12, 2020. /VCG

Ships sail during the second phase of the Malabar naval exercise in which India, Australia, Japan and the U.S. are taking part in the Bay of Bengal in the Indian Ocean, October 12, 2020. /VCG

Touting U.S. "capabilities" in the name of Tokyo's defenses won't remotely affect, in any way, China's exercise of its territorial rights over Diaoyu Islands. But it will provide more evidence of Washington's desire to advance confrontation under any pretext in the region. That is a bad look for the U.S.-Japan alliance. It calls into question what both leaderships deem essential to "enhance" their so-called "commitment to the region."

On "peace and stability" across the Taiwan Straits, what Kishida and Biden pay is nothing but lip service. It is lip service because the forces that campaign for instability, and harbor fantasies of an "independent" Taiwan, are those that are cheered-on by both nations. What this two-faced approach to the one-China principle indicates is a larger duplicity in U.S.-Japan offerings in Asia, particularly in the name of "cooperation."

As far as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is concerned, both Kishida and Biden reaffirm their support for the bloc's centrality, vowing to strengthen cooperation in the region. But on the maritime front, their allegation of attempted shifts in status-quo in the South China Sea sharply contrasts with the stated need of ASEAN: to maintain and promote an environment conducive to the South China Sea Code of Conduct (COC) negotiations. These negotiations represent a process of enhancing trust and confidence among recognized parties, not promoting toxic speculation about stable waters.

Observers can expect more misrepresentation of Asian security contours as Japan prepares to hold the next summit of Quad Leaders this spring. The grouping – which is yet to fully establish gains on climate, infrastructure, energy and anti-pandemic commitments – is likely to endorse Biden's Indo-Pacific Economic Framework proposal, and claim it as the interest of the region.

But given what largely commands the Quad and its China-focused containment ambitions, the proposed economic framework too is a U.S. prescription. It will be aimed at a region that generates most economic prescriptions on its own, and is less compelled to add teeth to a divisive Indo-Pacific strategy.

As Tokyo tags along, it is worth to ask – is this the aggregate strength of the U.S.-Japan alliance?

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)