A cargo ship is to dock at a container terminal. /CFP

A cargo ship is to dock at a container terminal. /CFP

Editor's note: Azhar Azam works at a private organization as a market and business analyst and writes on geopolitical issues and regional conflicts. The article reflects the author's views and not necessarily those of CGTN.

Joe Biden isn't keen to strengthen trade ties with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). In response to criticism that his strategy lacked an economic component, the U.S. president last October vowed to kick-start discussions on developing a regional economic framework but his aides immediately spelled out the initiative he referred to "is not a trade deal."

So far, the administration has provided very few details as to how it would engage Asia-Pacific. The lukewarm attempt has been lamented by the regional countries and is causing frustration in Biden's aides as his Indo-Pacific Coordinator Kurt Campbell stressed the U.S. should remain deeply involved "diplomatically, militarily, comprehensively (and) strategically" as well as economically in the region.

Washington promises to establish "common goals" on economic cooperation with the Indo-Pacific in early 2022; still it remains tight-lipped on rejoining trade deals such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTTP), Donald Trump withdrew from in 2017, over fear of losing American jobs.

Increased trade is essential to boost economic relations and has rightly been a primary focus of the Asia-Pacific, which has greatly benefited from China's rise and counts Beijing as its largest trading partner. Campbell's recognition of Beijing's "critical and important role" and pursuit for "a kind of coexistence" is a subtle acknowledgement the regional countries aren't comfortable with the United States' doomed, overly China-oriented Indo-Pacific strategy aimed at jeopardizing regional peace and growth.

China wasn't always considered a national security threat for the U.S.; it's just a recent phenomenon, shaking the White House. In 2014, then-U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry said "China and the United States represent the greatest economic alliance trading partnership in the history of humankind, and it is only going to grow. The State Department today is very clear that economic policy is foreign policy and foreign policy is economic policy."

Noting business and trade could strengthen national security, the U.S. State Department in early 2015 brought up an estimate that the $300 billion trade deficit with China could turn into $300 billion trade surplus and add three million new jobs in America if Chinese people were to consume U.S.-made goods and services at the same rate Japanese did.

Within a few years, Washington's pro-trade approach toward Beijing has been replaced by acrimony, hostility and recrimination. The U.S. administrations of late are more inclined to build an anti-China alliance in Asia-Pacific and elsewhere over contrived national security concerns, putting America's and Americans interests behind.

A comprehensive, nonviolent regional economic engagement continues to be a top priority of the Biden administration. It isn't. Not only does the U.S. president's Indo-Pacific economic framework lack a key element of trade; it purports to counter and offset China's "increasing economic influence" and "recent advances" into regional trade agreements including the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

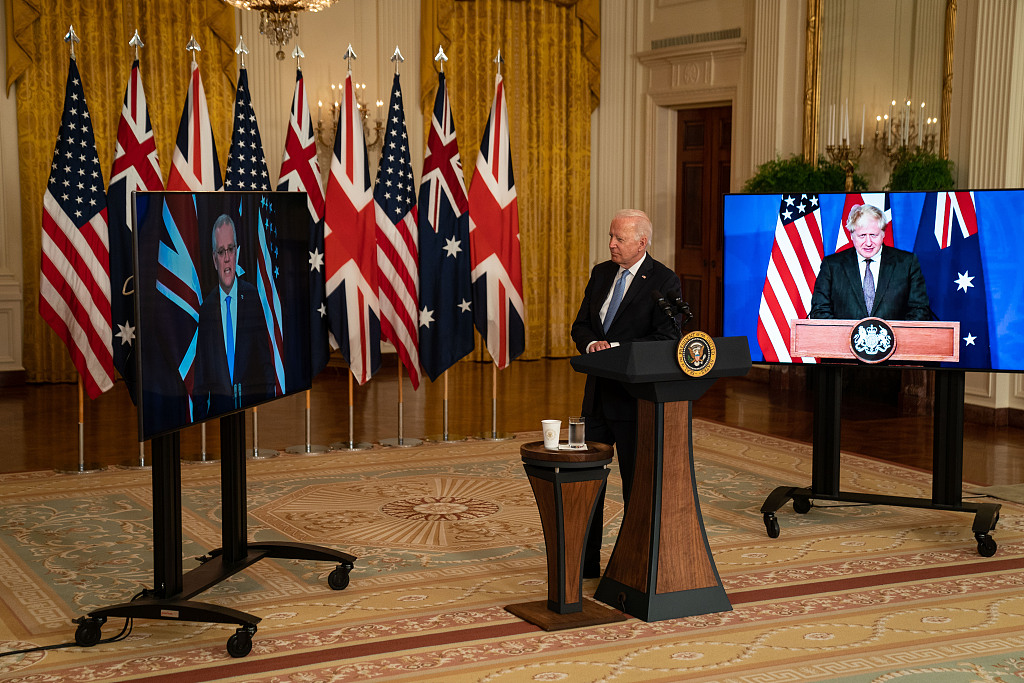

U.S. President Joe Biden announces that the U.S. will share nuclear submarine technology with Australia as he is joined virtually by Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, in the White House, Washington, D.C., U.S., September 15, 2021. /VCG

U.S. President Joe Biden announces that the U.S. will share nuclear submarine technology with Australia as he is joined virtually by Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, in the White House, Washington, D.C., U.S., September 15, 2021. /VCG

RCEP entered into force in January and brought together 15 East Asian and Pacific nations of different economic sizes and stages of development to form the world's largest trading block. A United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) study estimates the new Asia-Pacific free trade agreement would increase interregional trade by $42 billion, benefiting Japan the most with its exports expecting to rise by $20 billion.

The study raised the profile of RCEP, which is predicted to eventually eliminated 90 percent of tariffs between members, and emphasized it will account for almost one-third of global GDP compared to the South American trade bloc Mercosur (2.4 percent), Africa's continental free trade area (2.9 percent), the European Union (17.9 percent) and the United States-Mexico-Canada agreement (28 percent).

About 60 percent of seaborne trade, the UNCTAD calculates, passes through Asia and the South China Sea (SCS) carrying one-third of global shipping. The maritime trade is not only crucial for China, Japan and South Korea that rely on the Strait of Malacca, the CSIS ChinaPower reckoned the closure of waterways – connecting the SCS and the Pacific Ocean and Indian Ocean – could precipitate global supply chain disruptions, making Southeast Asia particularly vulnerable by inflicting up to $32 billion in damages.

Biden's Indo-Pacific economic framework intends to address issues such as trade facilitation, digital economy standards, supply chain resiliency, infrastructure, decarbonization and clean energy, export controls, tax and anti-corruption. But the regional countries, seeing China success a boon for the growth in the region, won't settle for anything less "substantial" to the CPTPP, which has "steadily garnered credibility and appeal."

After regional states expressed deep concerns over AUKUS, the trilateral alliance security pact, undermining regional peace by triggering an arms race and posing risks of nuclear proliferation, China and the ASEAN agreed to enhance mutual trust and maintain peace and stability in the SCS and promote active and comprehensive economic relations in trade, supply chain and other important areas.

Peaceful relations with all nations align with regional values of peace and impartiality. Rather than giving an affirmative response to the U.S. vexatious calls of "freedom" and "openness," they want stability in Asia-Pacific to quickly recover from the catastrophic impacts of the pandemic. Since Washington's push to rally alliances is geared toward stoking tensions by seeking support for a vague framework, not many countries are able to back the initiative that does little to bolster trade and concentrates profoundly on disturbing the regional growth-peace equation.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)