04:10

In 1953 and 1961, two highways cut through Boston Chinatown against the residents' will, displacing hundreds of families, in order to alleviate traffic downtown and allow white people living in suburbs the convenience of commuting to the city in cars.

The highways displaced far more than houses. Clean air, for one, is long gone. In 2018, Boston Chinatown still had the highest level of vehicle emissions in Massachusetts.

This incident is not an isolated event for communities of color, but one example of widespread environmental racism. It highlights the continued exposure of America's structural racism that places a disproportionate burden of environmental hazard on people of color, in the context of the warming planet and worsening environment.

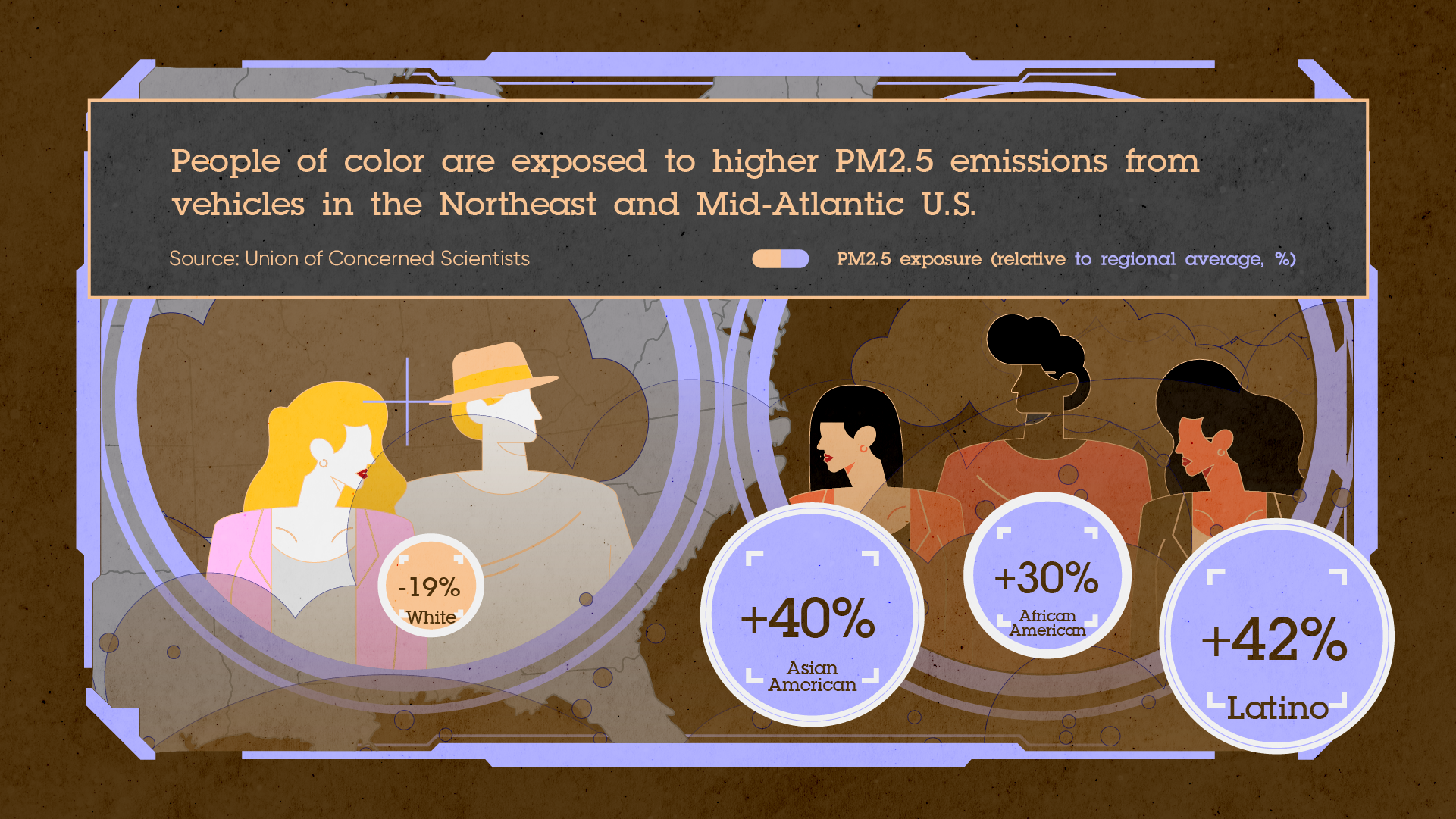

Firstly, in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic United States, covering Washington, D.C. and 12 states, residents of color are exposed to significantly higher PM2.5 emissions from vehicles than their white counterparts. Specifically, PM2.5 exposure for Latino, Asian American and African American residents is respectively 42, 40 and 30 percent higher than the regional average level, while exposure is 19 percent lower on average for white residents.

This disparity reflects decades of discriminatory transportation policies that have left communities of color living in segregated areas with inadequate access to public transportation, and close to highways, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists.

During the highway-building boom from the 1950s to 1960s in the U.S, the practice of interstate construction cutting through neighborhoods largely inhabited by people of color – where land was cheap and political opposition low – was so common that the critics coined a name for it: "White roads through Black bedrooms."

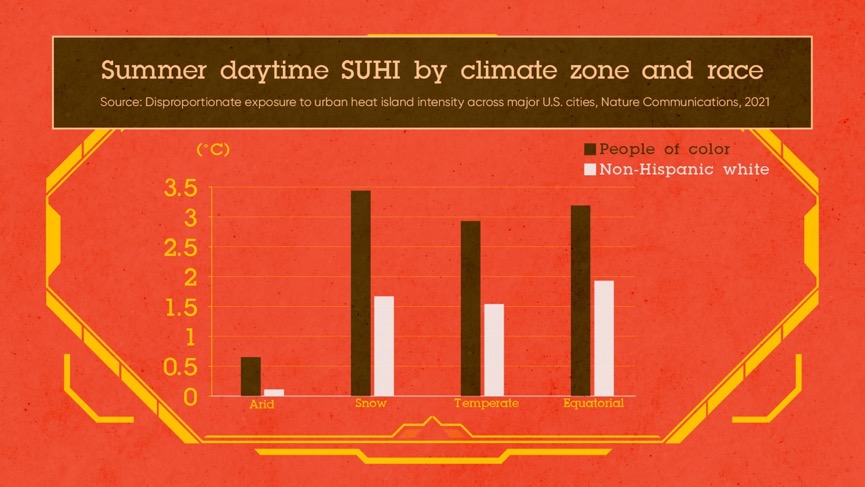

Secondly, using Surface Urban Heat Island (SUHI) data, research has found that in all but six of the 175 biggest U.S. cities, the average person of color lives in an area that has higher summer daytime temperatures than non-Hispanic white people.

SUHI data quantifies the contribution that cities' buildings, roads and infrastructure made to additional heat exposure temperatures. As shown in the graph, people of color have SUHI exposure of around 0.5, 1.8, 1.4 and 1.3 degrees Celsius higher than white people in different climate zones respectively.

Among the underlying drivers of these disparities, there is a correlation between warmer neighborhoods with the racist federal housing practices established during the 1930s called "redlining."

Assessed by federal officials as too hazardous for home loans and investment, formerly redlined neighborhoods have fewer environmental amenities that help to clean and cool the air. Tree canopy, for one, is roughly half of that in highest-rated predominantly white neighborhoods, according to a study of 37 U.S. cities published in Nature.

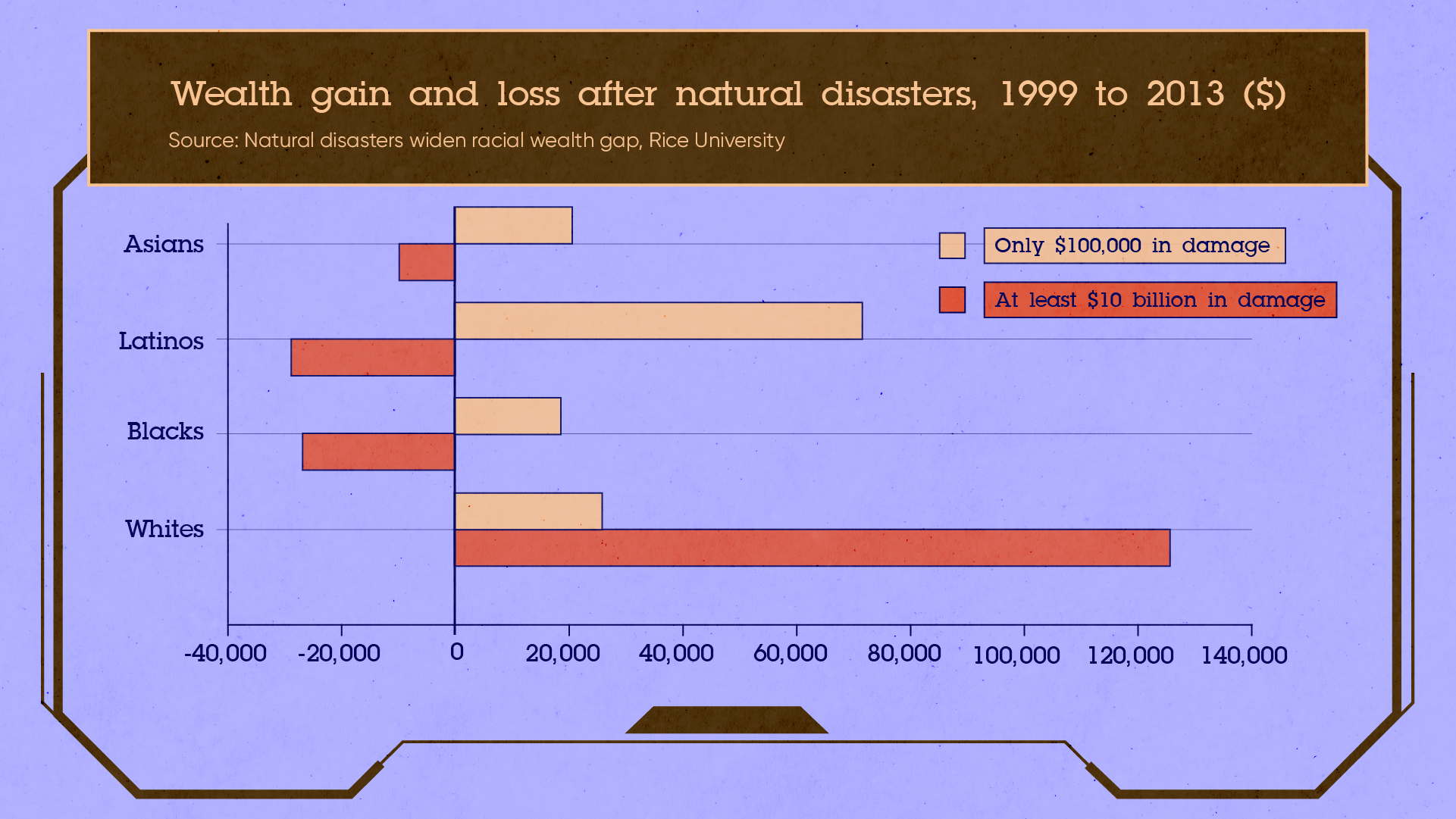

Thirdly, damage caused by natural disasters and subsequent assistance efforts have exacerbated the wealth gap among races in the U.S, and that has expanded the definition of environmental racism in America.

White people generally accumulated wealth after natural disasters like wildfires, floods and tornadoes. But among other racial or ethnic groups, disasters with damage above $10 billion could result in a financial loss of as high as $29,000.

Researchers found racial disparities at almost every stage of the process of applying for Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) assistance, resulting from differences in tax revenues and real estate values, among other issues.

For example, areas with a higher percentage of Black residents are less likely to get an inspection from FEMA to get repair funds. When homeowners in predominantly Black areas finally had their assistance applications approved, FEMA awarded them an average of five to 10 percent less money than applicants in white areas.

Environmental racism is racism that one could easily neglect – the intensity of green areas or the location of highways across neighborhoods isn't often seen through a racial lens. But it's there if you just breathe.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)