The excavation site of Xiamabei in the Nihewan Basin, north China's Hebei Province. /National Cultural Heritage Administration

The excavation site of Xiamabei in the Nihewan Basin, north China's Hebei Province. /National Cultural Heritage Administration

An international team including Chinese, French, and German archaeologists has reported a unique pigment-processing and stone-making culture of our immediate ancestors in northern China, offering a vivid picture of the hunter-gatherer lifestyle 40,000 years ago.

The study published on Thursday in the journal Nature described the earliest known ochre-processing example in East Asia, as shown by a distinctive miniaturized stone tool assemblage with bladelet-like tools bearing traces of hafting, and a bone tool.

The findings are based on Xiamabei, a well-preserved, approximately 40,000-year-old archaeological site in the Nihewan Basin, northern China. The site was found by the Hebei Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archeology (HPICRA) from 2013 to 2014.

"Xiamabei stands apart from any other known archaeological sites in China, as it possesses a novel set of cultural characteristics at an early date," said Wang Fagang with HPICRA, whose team first excavated the site.

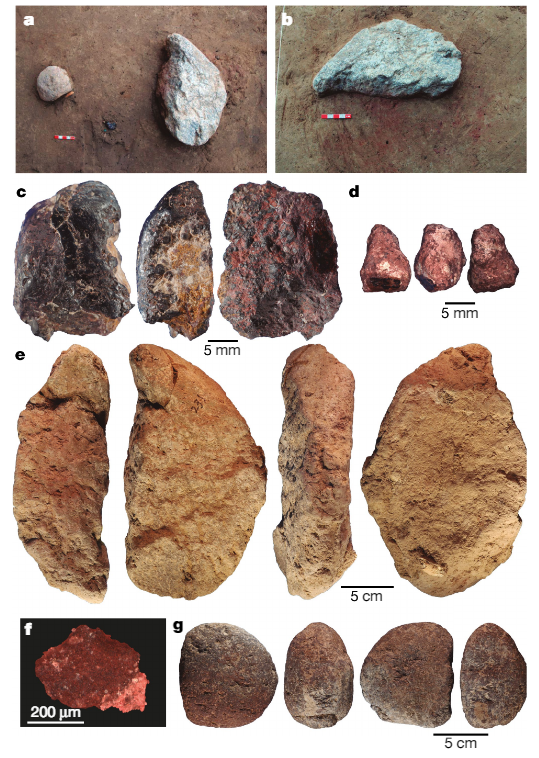

A screenshot of the study published in the journal Nature shows the artifacts laying on the red-stained sediment patch.

A screenshot of the study published in the journal Nature shows the artifacts laying on the red-stained sediment patch.

Miniaturized tools

The artifacts used to process large quantities of pigment found at Xiamabei included two pieces of ochre with different mineral compositions and an elongated limestone slab with smoothed areas bearing ochre stains, all on a surface of red-stained sediment, according to the study.

The researchers suggested that different types of ochre were brought to the site and processed through pounding and abrasion to produce powders of different colors and consistency.

The large majority of blade-like stone tools those ancestors used were miniaturized, more than half measuring less than 20 millimeters, and seven of those tools showed clear evidence of hafting to a handle and were used for boring, hide scraping, whittling plant material, and cutting soft animal matter.

The making of hafted and multipurpose tools demonstrated a complex technical system for transforming raw materials not seen at older or slightly younger sites, according to the study.

"The ability of hominins to live in northern latitudes, with cold and highly seasonal environments, was likely facilitated by the evolution of culture in the form of economic, social and symbolic adaptations," said Yang Shixia, a researcher with the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the paper's co-corresponding author.

Animal fossils and bone tools unearthed from the archaeological site of Xiamabei in north China. /National Cultural Heritage Administration

Animal fossils and bone tools unearthed from the archaeological site of Xiamabei in north China. /National Cultural Heritage Administration

New evolution scenario

The researchers also suggested the visitors to Xiamabei were Homo sapiens thanks to their use of hafted tools and ochre processing. But it may reflect an early colonization attempt by modern humans, in wanting of formal bone tools or ornaments.

This colonization period may have included genetic and cultural exchanges with archaic groups, such as the Denisovans, before ultimately being replaced by later waves of Homo sapiens using microblade technologies, according to the study.

The researchers said the Xiamabei record does not fit with the idea of continuous cultural innovation, or a fully formed set of adaptations that enabled early humans to expand out of Africa and around the world.

They argued for the mosaic of innovation patterns, with the spread of earlier innovations, the persistence of local traditions, and the local invention of new practices all taking place in a transitional phase.

"Our findings show that current evolutionary scenarios are too simple," said Michael Petraglia with the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and the paper's co-corresponding author.

"And that modern humans, and our culture, emerged through repeated but differing episodes of genetic and social exchanges over large geographic areas, rather than as a single rapid dispersal wave across Asia."

Source(s): Xinhua News Agency