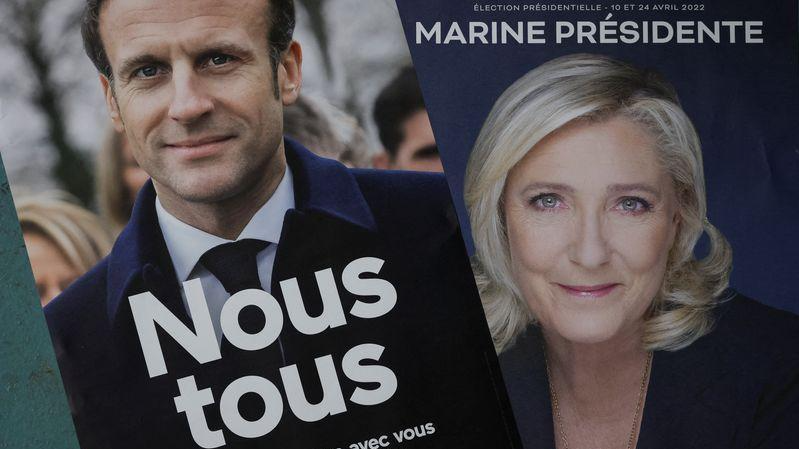

Official French presidential election campaign posters. /Reuters

Official French presidential election campaign posters. /Reuters

On April 24, the second round of France's presidential election will once again see centrist Emmanuel Macron face off with far-right Marine Le Pen.

In the first round of voting, incumbent President Macron received 27.8 percent of the votes, while Le Pen received 23.2 percent, knocking out the other 10 candidates and sending the two to run-off voting for the second election in a row.

In the first round of voting for the 2017 election, Macron received 24.01 percent and Le Pen 21.3 percent, only for Macron to defeat his opponent by a devastating margin in the second round with 66.1 percent to her 33.9.

However, this time around that gap is expected to be far more narrow. Polling by Ifop-Fiducial showed that the second round could be 51 percent to 49 percent in favor of Macron, while a poll published by Reuters estimates Macron could receive 54 percent and Le Pen 46 percent. But what has led to such an unexpected narrow margin, particularly with two candidates that represent very different political ideals? And what struggles do the candidates face?

One obstacle for Macron and Le Pen will be voter apathy. According to Ifop, participation in the first round of voting was an estimated 73.3 percent, the lowest in 20 years. With Jean-Luc Melenchon just barely missing the cut off in the first round with 22 percent of the votes, it is unknown for certain where votes for the eliminated far-left politician will fall — if cast — when it comes to the remaining candidates.

After coming in third in the first round, Melenchon said that "not a single vote" must go to Le Pen. However, he did not publicly back nor encourage his supporters to vote for Macron.

French President Emmanuel Macron talks to residents after voting in the first round of France's presidential election at a polling station in Le Touquet, northern France, April 10, 2022. /AFP

French President Emmanuel Macron talks to residents after voting in the first round of France's presidential election at a polling station in Le Touquet, northern France, April 10, 2022. /AFP

Macron himself has faced declining approval ratings during his first term with protests from the Yellow Vest movement and the country's battle to overcome the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, he is facing what Bruno Cautres, a politics professor at Sciences Po in Paris, calls an "anti-Macron" front that he did not have to contend with as a fresh-faced newcomer in his first bid for president in 2017.

Even with a lead over his opposition, Macron is aware that voter turnout is the key to securing his position.

"Nothing is settled and the debate that we will have in the coming 15 days is decisive for our country and our Europe," Macron said in a speech after polls had closed in the first round of voting on April 10. "I don't want a France which, having left Europe, would have as its only allies the international populists and xenophobes. That is not us. I want a France faithful to humanism, to the spirit of enlightenment."

French far-right presidential candidate Marine Le Pen (R) speaks to the press with French farmer and former president of the local rural syndicate Thierry Blanc (L) during a visit of his grain farm in Soucy, Burgundy, France, April 11, 2022. /AFP

French far-right presidential candidate Marine Le Pen (R) speaks to the press with French farmer and former president of the local rural syndicate Thierry Blanc (L) during a visit of his grain farm in Soucy, Burgundy, France, April 11, 2022. /AFP

Macron was referencing Le Pen's previous agenda of isolationism – an agenda she has adapted in the recent campaign. This is her third attempt to become France's first female president and while polls show a victory could be possible, it hasn't been without strong efforts on her part to rebrand her party, position and personal image.

Her strong anti-immigration stance and priority given to native French with regard to welfare benefits remains, but Le Pen insists there is no plan for France to leave the EU. She however has called for France to pull out of NATO's integrated command structure, "so as to no longer be caught up in conflicts that are not ours."

Her focus on the cost of living and rising energy costs have helped her in her primary voter strongholds—areas of France where those of lower socioeconomic standards are hit hard.

According to an analysis by Reuters, these areas most affected by the rising cost of living and crime, with a demographic of less education and a lower life expectancy, will present a hard front for Macron, whose base is mostly comprised of "educated, middle-class city dwellers."

While Macron began campaigning much later than Le Pen, in the wake of the first round of voting, Macron planned to "go to the ground."

In an effort to garner more votes, Macron has pivoted his campaigning efforts toward France's "industrial heartland," where Le Pen has been held as a favorite, though it is unclear how successful he will be in shedding a persona many perceive as "elite." His first campaign stop after the first round of voting was the poor northern town of Denain.

If Macron does indeed win, he will be the first French president to be reelected in 20 years. And according to Cautres, even then, it won't be an easy term.

"It will be much harder for him and his reform campaign," said Cautres. "He has to respond to demands for social justice [...] There will be strong political tensions."