An electric bus on Beijing's Chang'an Avenue. As of 2020, the Chinese capital added more than 11,000 e-buses to its fleet, which covered all the buses plying in Beijing's downtown area and its sub-center. /China.org.cn

An electric bus on Beijing's Chang'an Avenue. As of 2020, the Chinese capital added more than 11,000 e-buses to its fleet, which covered all the buses plying in Beijing's downtown area and its sub-center. /China.org.cn

Editor's note: Abhishek G Bhaya is a senior journalist and international affairs commentator. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

India's national capital New Delhi, my hometown, has embarked on an ambitious plan of electrifying its entire public transport fleet in the next few years, a much-needed measure for the city of 20 million that has had the unenviable distinction of being the world's most polluted capital in recent years.

Several Indian cities are among the most polluted – automobile emission being one of the key causes – and are in desperate need to rapidly switch to new energy vehicles (NEVs) on a large scale, beginning with city buses used by millions for daily commute.

On Tuesday, as I cherished the reports of the Delhi state government flagging off 150 new electric buses with plans of including 2,000 e-buses in the next few years with an ultimate goal of having a 100 percent fleet of 11,000 e-buses, I couldn't help reflecting on the remarkable and relatable transition witnessed in Beijing, which has been my home for the past five years, and the lessons that India might draw from the Chinese experience. Coincidentally, Beijing and New Delhi happen to be sister cities since 2013.

I arrived in the Chinese capital in August 2017, precisely around the time when Beijing Public Transport Corporation (BPTC) embarked on a mission to increase the city's e-bus fleet from 1,000 to 10,000 by 2020, accounting for 60 percent of Beijing's total fleet of public buses. In the next three years, I witnessed the massive rollout of e-buses in the city.

These sleek, clean, comfortable, noiseless and zero-emission buses soon became a part of my daily life as I would often use their efficient services – most routes are trackable on Smartphone GPS apps – to commute between home and work and also to explore the city.

By 2020, Beijing added more than 11,000 e-buses to its fleet – surpassing its original target. These covered all the buses plying in Beijing's downtown area and the city's sub-center. Today, living in downtown Beijing, I rarely come across a fossil fuel-based public bus.

India's capital New Delhi flagged off 150 new electric buses on May 24, 2020, with plans of including 2,000 e-buses in the city's public transportation in the next few years with an ultimate goal of having a 100-percent fleet of 11,000 e-buses. /Government of Delhi

India's capital New Delhi flagged off 150 new electric buses on May 24, 2020, with plans of including 2,000 e-buses in the city's public transportation in the next few years with an ultimate goal of having a 100-percent fleet of 11,000 e-buses. /Government of Delhi

The positive fallout of this initiative on the environment of Beijing – which was once infamous for its smog and, like Delhi, was counted among the world's most polluted cities – can't be more distinct, and thoroughly appreciated and vouched by its 22 million residents. As clear as a day, quite literally!

By September 2019, the Chinese capital was no longer on the list of the world's top 200 most polluted cities. In August 2020, referring to the city's cleaner air and bluer sky, China's Minister of Ecology and Environment Huang Runqiu famously said that "the 'Beijing blue' has gradually become our new normal," as he declared that the country has successfully achieved its phased goals in curbing pollution.

Adopting a proactive policy on e-vehicles is among the key factors behind China's triumph against its nationwide air pollution problem. In 2009, Shenzhen was selected as the first of 13 pilot cities to cut down vehicle emissions by introducing NEVs, including electric cars and buses. By the beginning of 2018, the city of 12 million people had replaced all its public buses with more than 16,000 e-buses, becoming the world's first city to have a 100 percent e-bus fleet. Shenzhen also has a fleet of 22,000 electric taxis.

According to the latest available data, released by the Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment in October 2020, China's clean energy drive has replaced 60 percent of the country's buses with electric vehicles, up from 20 percent in 2015.

China leads the global e-bus drive

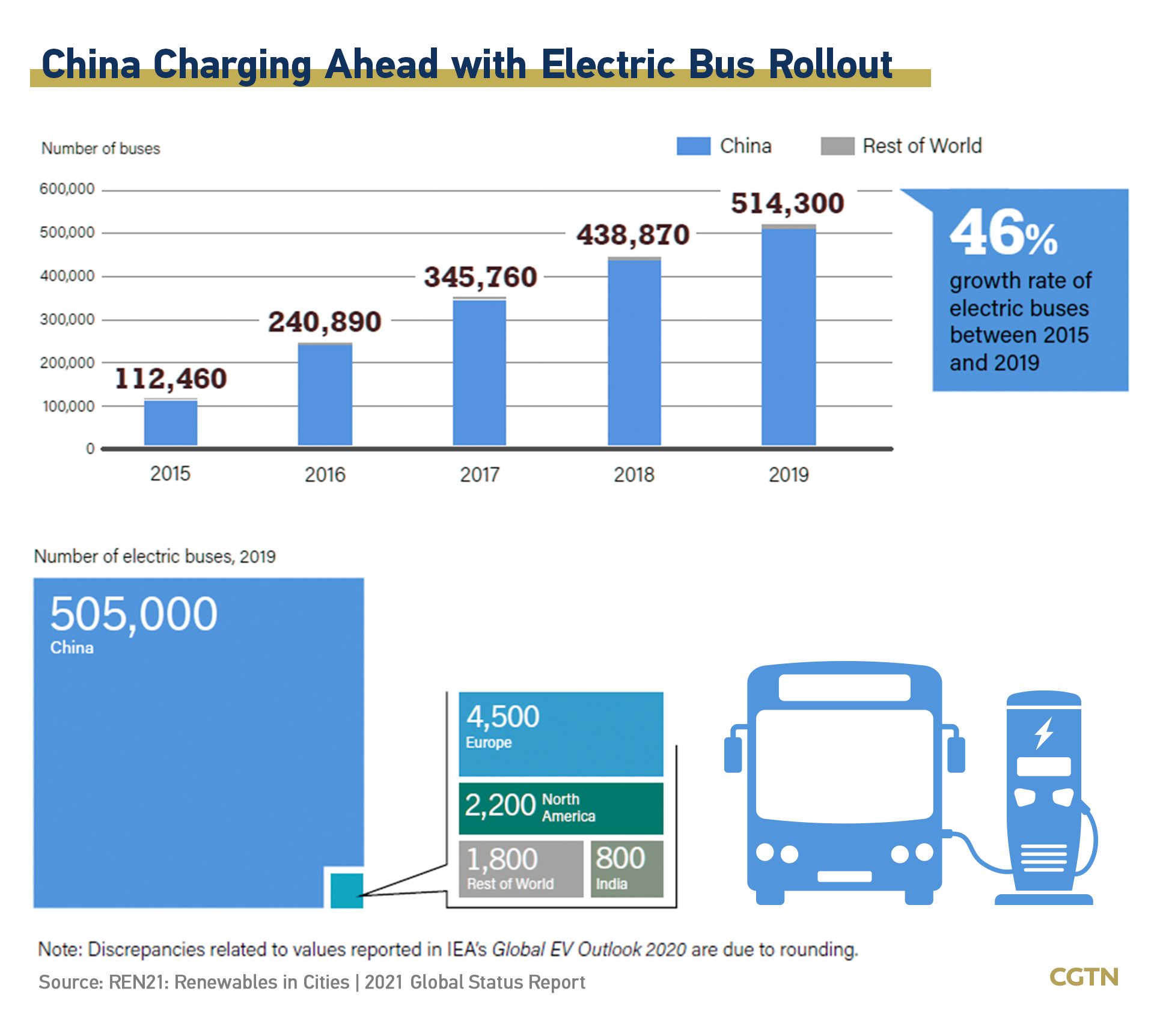

Today, China has not only emerged as the world's largest manufacturer of NEVs accounting for 55 percent of the global NEV sales, but also the largest market for e-buses. By the end of 2019, there were over half a million electric buses in use around the world, of which 98 percent were running on Chinese roads. In comparison, Europe had 4,500, North America 2,200, India 800, and the rest of the world accounted for 1,800 e-buses.

The shift from conventional fossil fuel-based vehicles to e-buses has made a huge positive difference to China's public transportation system and its environment. China has pledged to achieve carbon neutrality before 2060, and its mammoth e-vehicle drive is a key step in reaching that goal in time. According to studies, electric buses consume about 73 percent less energy than buses that run on diesel, and the annual CO2 emission for e-buses is estimated at 67.02 kg per 100 km compared to 129.91 kg for diesel vehicles – a reduction of about 48 percent.

China's phenomenal success in the electrification of more than half its public transportation in just a little over a decade holds many lessons for India, which has set out an ambitious sustainable urban mobility agenda supporting the government's plans to reduce carbon emission by up to 35 percent by 2030. If successfully executed, India's e-bus rollout, like China's, will be a cornerstone in accelerating New Delhi's efforts in meeting the country's net-zero target by 2070 as part of its commitment to the Paris Climate Agreement.

The target is a huge challenge considering India's dubious record of having one of the world's worst air qualities, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO). In 2021, India was home to 63 of the world's 100 most polluted cities, including 10 in the top 15. Vehicular emission is clearly one of the top sources of air pollution, and a complete transition to NEVs remains the most viable and sustainable long-term solution, keeping with India's emission targets.

A thick layer of smog is seen in New Delhi, India, October 13, 2020. Vehicular emission remains one of the top sources of air pollution in several Indian cities. /CFP

A thick layer of smog is seen in New Delhi, India, October 13, 2020. Vehicular emission remains one of the top sources of air pollution in several Indian cities. /CFP

India needs to take a leaf from China's playbook

In 2017, India's Minister of Road Transport and Highways Nitin Gadkari announced a plan to have only electric vehicles on Indian roads by the end of 2030, a target that he has since revised owing to various factors including the economic disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. As per the minister's new target, India is aiming to have 30 percent of private cars, 70 percent of commercial vehicles, 40 percent of buses and 80 percent of two- and three-wheelers replaced by electric options.

The government also aims to locally manufacture electric vehicles to meet domestic demands while also targeting exports. According to a recent report by research organization WRI India, the South Asian country requires over 100,000 e-buses by 2030, which means scaling up its deployment to an average 11,000 e-buses annually for the next nine years. Despite the reasonable challenges, the target is achievable. India needs to look no further than its northern neighbor.

China is the only country that has increased its electric bus stock from 111,000 units in 2015 to 505,000 in 2019, effectively adding about 80,000 e-buses annually to its national fleet. This astounding success was made possible due to the Chinese government's long-term vision, conducive policies including subsidies for purchasing e-vehicles, and what China Automotive Technology and Research Center (CATRC) described as the electric vehicle industry's adoption of a "3-Steps" development strategy.

Step 1 covers the three-year period from 2009 to 2012, when the initial electric vehicle market was expanded through the establishment of pilot demonstrations in 13 cities. Step 2 covers the next two-year period from 2013 to 2015, which focusses on further development and expansion of the market by raising the number of pilot cities and city clusters. And since 2016, the strategy has entered Step 3 comprising nationwide mass adoption of electric buses.

It is to be underlined here that the economic benefits of e-bus service far outweigh the initial high cost of e-bus rollout. And a key element for smooth operation of the service is the construction of related infrastructure including, most importantly, a charging facility network across the country. China has so far built some 810,000 public charging stations and is on track to boost charging services to meet the demand for an estimated 20 million e-vehicles including e-buses by 2025. India currently has only 1,742 public charging stations.

Considering the comparative population size and similar urban planning challenges of the two Asian neighbors, India will do well to borrow a leaf or two from the Chinese playbook in the next stages of its e-bus rollout. Collaboration and joint ventures with experienced Chinese e-vehicle makers can expedite India's local manufacturing ambition. Chinese technical know-how in building support facilities could also offer a roadmap for laying India's e-bus infrastructure at a scale that's not available elsewhere. India's smartphone industry has benefited from similar cooperation with Chinese firms.

China and India are both members of several multilateral organizations such as BRICS and Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which can also be leveraged for multilateral cooperation between member countries on e-vehicles as part of "deepening innovative cooperation on the new industrial revolution for achieving sustainable development goals in a stronger, healthier and more resilient manner."

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com. Follow @thouse_opinions on Twitter to discover the latest commentaries on CGTN Opinion section.)