04:26

When Black American Adam Solveig was walking home with his friend in New York City, he heard the hammer from a gun click and thought he was subject to an armed robbery. But behind him were actually police officers, having drawn their guns unannounced.

"So what do I do? Do I run?" he asked himself. It is a question that not only consistently baffles Black Americans but also reflects a long history of controversial police shootings that warrant such strong concern from the Black community.

"I could have been dead. That's normal policing in America," Solveig said, sinking into thought as he recalled his encounter.

On April 4, Patrick Lyoya, a 26-year-old refugee from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was fatally shot in the back of his head by a white police officer in Grand Rapids, Michigan. The killing followed a scuffle between the two men during a traffic stop. The officer claimed he shot Lyoya in self-defense. He has been charged with second-degree murder.

Similar cases are numerous, and Black Americans are more than twice as likely as their white counterparts to be killed by police, according to data gathered by The Washington Post.

But the police targeting of African Americans, which also includes a disproportionate number of arrests, stop-and-frisks and imprisonments, appears only to be a microcosm of entrenched racial disparities in the United States. Statistics from the U.S. Department of Justice reveal that African Americans are three times more likely to be jailed if arrested.

Protesters stand separated from the police by a barricade as they march for Patrick Lyoya, a Black man who was fatally shot by a police officer, in downtown Grand Rapids, Michigan, U.S., April 16, 2022. /CFP

Protesters stand separated from the police by a barricade as they march for Patrick Lyoya, a Black man who was fatally shot by a police officer, in downtown Grand Rapids, Michigan, U.S., April 16, 2022. /CFP

"I feel like it was a long time coming, between the police brutality, the economic disparity, the wealth gap, just the underlying racial tones going on in America. It was like a boiling pot," Solveig said.

The police killing of George Floyd in 2020, which sparked waves of worldwide protests against racial injustice, brought to the fore the sharp disparities between Black and white Americans, a plight that experts say is intrinsically difficult to eradicate.

The sharp disparities

Black Americans often have to grow up in adverse environments where the lack of access to good education, jobs, equal pay and loans make it more likely for them to remain poor, a vicious cycle that leads to and is also exemplified by the huge wealth gap between Black and white Americans. According to the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, the average Black household has a net worth of only $142,500, which is 14 percent that of their white counterparts. A report published in April by National Urban League, a civil rights organization, also noted a median household income for Blacks at nearly $44,000, which was 37 percent less than that of whites.

"Racial inequality persists in our contemporary, putatively color-blind system; due to discrimination, Black people receive lower valuations on their homes and earn less money compared to white people performing the same work. Biases in public investment and criminal justice leave Black communities simultaneously underserved and over-policed, and these civil rights violations also have serious economic consequences," Vanessa Williamson, a senior fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution, wrote in an article published by the organization.

Williamson noted that elected officials have for decades unfairly blamed racial disparities on personal choices, adding that the racial wealth gap should instead be "recognized as the consequence of discrimination, public and private, throughout American history and continuing to this day."

Systemic racism in one of its most overt versions was the organizational treatment of Blacks as property, a deep-seated propensity that evolved from slavery. But as civil rights movements progressed, institutional racism and its ramifications, subtle or overt, did not subside. One example that spoke volumes about how historical racist policies have impacted African Americans' modern-day livelihood is redlining, a practice that deprived Black neighborhoods of the benefits of federal mortgage support.

A Bank of America branch in New York, U.S., January 17, 2022. /CFP

A Bank of America branch in New York, U.S., January 17, 2022. /CFP

Originated from government homeownership programs created in the 1930s to fight the Depression, redlining was used to determine the loan worthiness of neighborhoods based on the prospect of property values. Unsurprisingly, communities deemed unworthy of loans were predominantly Black, which researchers say helped expand segregation among Americans along racial lines. Despite a ban on housing discrimination in 1968, the practice has continued until today. Studies show that real estate agents keep steering homebuyers away from certain neighborhoods, and banks still turn African Americans away at rates far greater than whites.

"From the brutal exploitation of Africans during slavery, to systematic oppression in the Jim Crow South, to today's institutionalized racism ..., government policy has created or maintained hurdles for African Americans who attempt to build, maintain, and pass on wealth," Christian E. Weller, a professor of public policy at the McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies at the University of Massachusetts, and Lily Roberts, the managing director for Economic Policy at American Progress, wrote in an article published by the Center for American Progress.

Where is it headed?

The massive wealth gap is nothing new in America, but Democratic politicians increasingly realize the electoral importance of addressing the matter. The Biden administration, which secured its election victory on the back of the Black Lives Matter movement, has vowed to take concrete measures to narrow the generational divide.

A key action Biden took was his executive order on "Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government," which policy experts said would help the federal government become an exemplar for making public employment more accessible to Black Americans.

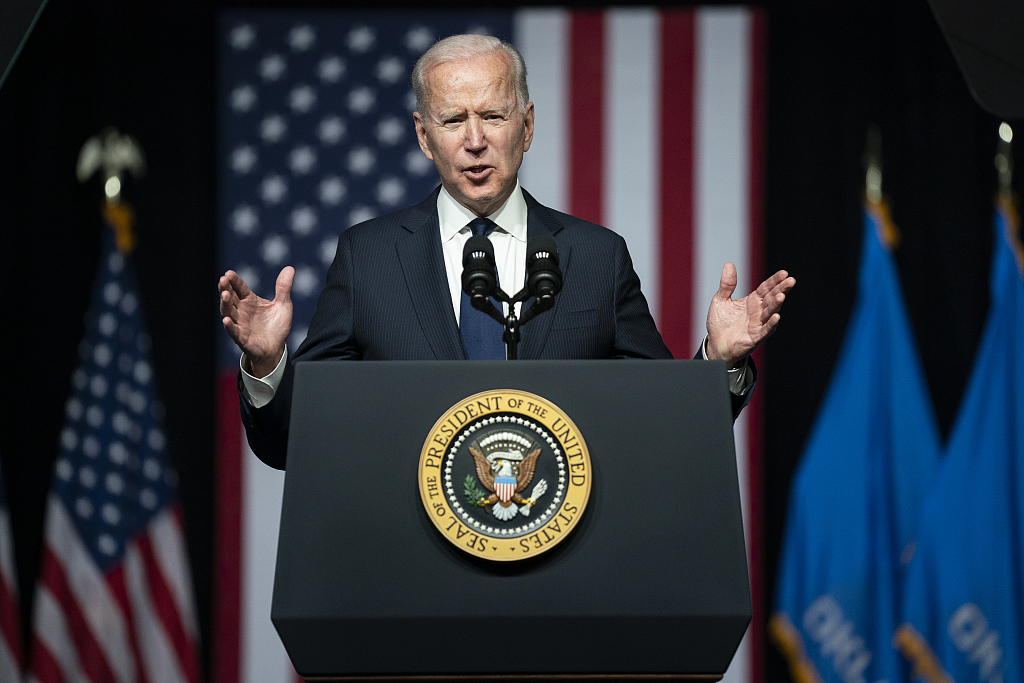

President Joe Biden commemorates the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa race massacre at the Greenwood Cultural Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma, June 1, 2021. /CFP

President Joe Biden commemorates the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa race massacre at the Greenwood Cultural Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma, June 1, 2021. /CFP

This and other federal measures have laid the groundwork for long-term progress, but government officials acknowledge that more extensive action and much longer commitments are needed to overcome the systematic, centuries-long challenges.

Meanwhile, the prospect of fixing the ingrained social predicament has further dimmed with the emergence of COVID-19. With Black Americans experiencing more exposure to the virus, poorer access to food and greater vulnerability to the economic recession induced by COVID-19, "the pandemic has created the perfect storm of factors that will drive wealth for African Americans and white households even further apart," Weller and Roberts noted.

The deteriorating and prolonged disparities are inevitably amplifying the sense of disappointment and grievances felt by Black Americans. As a photographer who likes to capture what's going on in New York, Solveig urged people to look more closely into what's causing the pain.

"Protest is when people get so hurt emotionally, they have no other way to let you know but to act out," he said.