04:56

When Navajo Nation resident Dawn Lynn Nez was diagnosed with COVID-19 in October last year, she locked herself inside her house. Then a single mom of five kids, she lacked food and medicine, not to mention medical assistance. But she saw no other choice.

“I was so scared, I was so devastated, especially for my little ones,” Nez told CGTN.

Nez was hardly the only Navajo who felt that way. Navajo Nation quickly surpassed all states to have the highest per capita COVID-19 infection rate in the U.S., despite having enforced some of the toughest social distancing measures in the country.

At its peak in 2020, the territory had 2,304 cases per 100,000 people. The rate for New York, which made headlines around the world as it struggled to contain the virus, was 1,806 cases per 100,000.

The question for many was not why it had happened – lack of access to quality health care and poverty were documented in a 2020 report published in The Journal of Rural Health – but why the underlying conditions fueling the spread were allowed to take root.

Since its founding in 1868, Navajo Nation has been in a treaty relationship with Washington. In exchange for giving up their original homelands, the U.S. government promised through laws to protect the Native population and support their development. Yet, as the U.S. government itself has long acknowledged, those promises have largely fallen short.

“Native Americans still suffer higher rates of poverty, poor educational achievement, substandard housing, and higher rates of disease and illness. Native Americans continue to rank at or near the bottom of nearly every social, health and economic indicator,” according to a report published by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in 2003.

Raynelle Hoskie attaches a hose to a water pump to fill tanks in her truck outside a tribal office on the Navajo reservation in Tuba City, Arizona, on April 20, 2020. /AP

Raynelle Hoskie attaches a hose to a water pump to fill tanks in her truck outside a tribal office on the Navajo reservation in Tuba City, Arizona, on April 20, 2020. /AP

Today, with a population of more than 390,000 people, Navajo Nation is the most populous tribal nation in the U.S. Its territory overlaps three states – Arizona, New Mexico and Utah – yet living standards fall far behind the U.S. national average.

Roughly four in 10 Navajo people live below the federal poverty threshold, while the territory's per capita income is one third that of the U.S. as a whole, according to Navajo Nation's official statistics. It also lags significantly behind the rest of the country in literacy and life expectancy due to a lack of federal funding over many decades.

On the reservation, which is the size of West Virginia, there are only 11 grocery stores. About 30 to 40 percent of the population has no access to running water, according to government statistics. Many locals are forced to use outdated ways to pump out groundwater or drive several hours to reach a water point to fill a tank.

Toxic legacy

Between 1944 and 1986, the U.S. government extracted nearly 30 million tonnes of uranium ore from the Navajo Nation to create atomic weapons and fuel nuclear power plants.

Most of these mines have now been abandoned, but they were never properly cleaned up.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that many of the mines sit in aquifers, which local communities rely on for water. Mining operations that drill into these aquifers can cause radioactive material to leach into the water, contaminating both the underground supply and the water absorbed from the surface.

More than 500 abandoned uranium mines have been left behind in Navajo Nation, and each poses the risk of continued spread of radioactive particles through air and water.

Uranium mining has caused higher rates of cancer, respiratory diseases, kidney problems and other various chronic conditions, especially among local miners and communities living in close proximity to the mines. According to Navajo Nation's statistics, cancer rates doubled on the reservation between 1970s and 1990s.

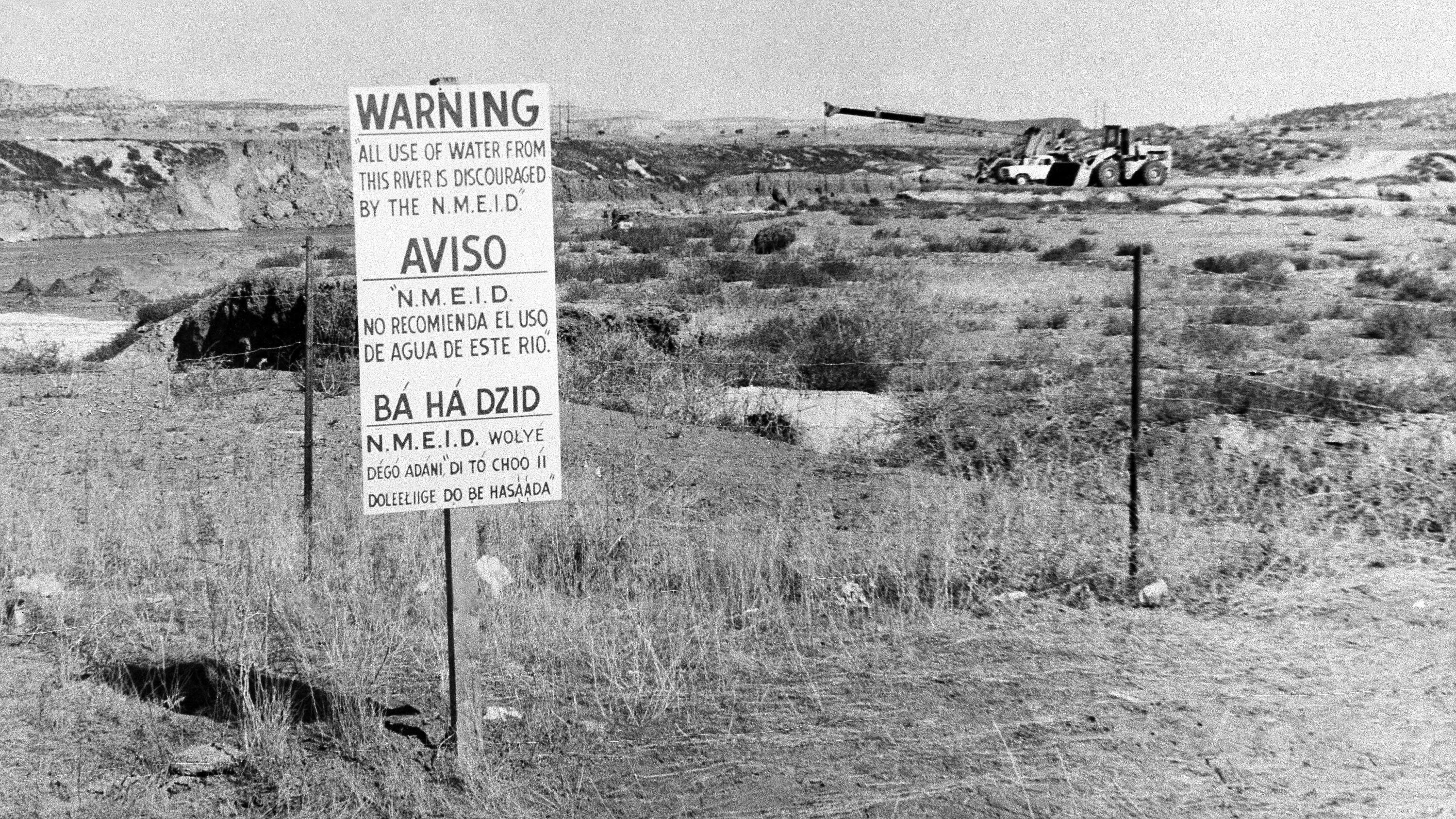

This November 13, 1975, file photo, shows signs along the Rio Puerco warning residents in three languages to avoid the water in Church Rock, N.M. after a uranium tailings spill. /AP

This November 13, 1975, file photo, shows signs along the Rio Puerco warning residents in three languages to avoid the water in Church Rock, N.M. after a uranium tailings spill. /AP

Yet, neither the federal government nor the mining companies have made any substantial effort to reduce or mitigate the harmful and often deadly effect of these mines.

“The tragic legacy of uranium mining on the Navajo Nation continues to this day, perhaps to an extent that would not have occurred if it weren't taking place in a rural American Indian community,” Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez told a House Judiciary subcommittee in March. In prior testimony, he referred to the Navajo's “horrible legacy,” and said that “past uranium activity has devastated Navajo families, traditions, and our Mother Earth.”

History of abuse

Known as the “Long Walk of Navajo,” more than 10,000 Navajo men, women and children were removed at gunpoint by the U.S. military from their ancestral homelands between 1863 and 1866 and were forced to march between 400 to 725 kilometers to an internment camp known as Bosque Redondo, located in today's New Mexico.

Hundreds died from hunger, thirst and exhaustion while those who failed to keep up, including pregnant women, were shot dead by American soldiers.

According to the testimony of John Daw, the last surviving U.S. Army Indian Scout, whose parents and grandparents were part of the treacherous journey, the soldiers did not “have any regard for the women folks. They took unto themselves for wives somebody else's wife, and many times the Navajo man whose wife was being taken tried to ward off the soldiers, but immediately he was shot and killed and they took his wife.”

Once arriving at the camp, guarded by armed soldiers, survivors were forced to assimilate to white American cultural values and acquire “new habits, new ideas, new modes of life,” according to Navajo Roundup: Selected Correspondence of Kit Carson’s Expedition against the Navajo by Lawrence C. Kelly.

Through “civilizing” the “young ones,” the Navajos would become a “happy and contended people,” argued Major General James H. Carleton, who oversaw the long walk.

“Navajo Nation has been a national sacrifice area for the U.S. for two centuries,” Ethel Branch, former attorney general of the Navajo Nation and chairperson of the Navajo and Hopi Families COVID-19 Relief Fund, told CGTN.

“We're equal human beings, we're the original people of these lands. Our interest needs to be considered and protected just as much as any other American. Or what's the point of being American?”