04:07

The Greenspring Retirement Community, hidden deep in the Virginia woodland, is much like any other high-end senior care facility in the United States, yet a curious incident three years ago has placed it firmly in the spotlight.

In the summer of 2019, some residents on the scenic 58-acre campus close to Washington D.C. fell ill to an unknown respiratory illness. Three died and 23 went to hospital within days. Local officials admitted in the following month they found "higher-than-usual" respiratory illnesses, according to The Washington Post.

The tragedy baffled the residents of Greenspring. Why did a respiratory illness, usually seen in winter, blitz them in a scorching July? No one offered an answer, nor any clue as to where the virus came from.

Military personnel stand guard outside the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick, September 26, 2002. /CFP

Military personnel stand guard outside the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick, September 26, 2002. /CFP

Does Fort Detrick have secrets to tell?

Three years after the Greenspring incident, little is known about what really happened. No one at the community wanted to talk about the deadly outbreak when a CGTN stringer visited there last year. The local community administration also declined an interview request.

But a secretive military germ lab about an hour's drive from Greenspring may offer some answers.

The U.S. has built a complex network of labs to research the most dangerous viruses on the planet, but a lack of transparency and frequent safety infringements make these facilities a danger to the public.

About the same time as staff at Greenspring were scrambling to deal with the strange outbreak, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shut down the biological warfare research center, better known as Fort Detrick, for unspecified "national security reasons."

Fort Detrick stores batches of the most dangerous toxins known to mankind, including Ebola, anthrax and the SARS coronavirus.

The suspension was so sudden that some local officials got the information from news reports.

The CDC concluded the facility wasn't capable of decontaminating the wastewater it produces, according to a New York Times story published in August, a month after the shutdown. The lab was also found to have other potential risks, including not following the procedures consistently and mechanical problems with the chemical-based decontamination system.

"A combination of things" led to the final suspension, the New York Times reported.

Carol Krimm of the Maryland House of Delegates was among those who raised questions about the shutdown, and urged the CDC to be more transparent over any health and safety risks the center posed.

A local advisory committee also penned an open letter condemning the military's lack of transparency, warning that irresponsible actions by the Army could make high-containment laboratories like Fort Detrick high risks to local residents.

But the efforts yielded nothing concrete as the CDC didn't provide details of the issues. A few months later, Fort Detrick fell off the CDC's priorities list as the agency reported the first COVID-19 case it identified in the country.

Nevertheless, the time proximity between the Fort Detrick shutdown and the COVID-19 outbreak has raised questions. Silence from the authorities further ignited speculation over the government's decision to keep details of Fort Detrick secret.

In March 2020, a petition asking the U.S. to disclose information related to Fort Detrick, especially the reason why the lab was shut down in 2019 and whether it had anything to do with COVID-19, was filed on the White House petition website. The Trump administration didn't respond to the request.

In July 2021, another online petition calling for the World Health Organization (WHO) to investigate the Fort Detrick biological lab garnered 25 million signatures and millions of comments from around the world in three weeks. The U.S. ignored the requests and didn't open Fort Detrick to the WHO.

However, the history of Fort Detrick gives a clear picture of just how worrisome the lab can be, and how easily things can go wrong inside the U.S. lab network.

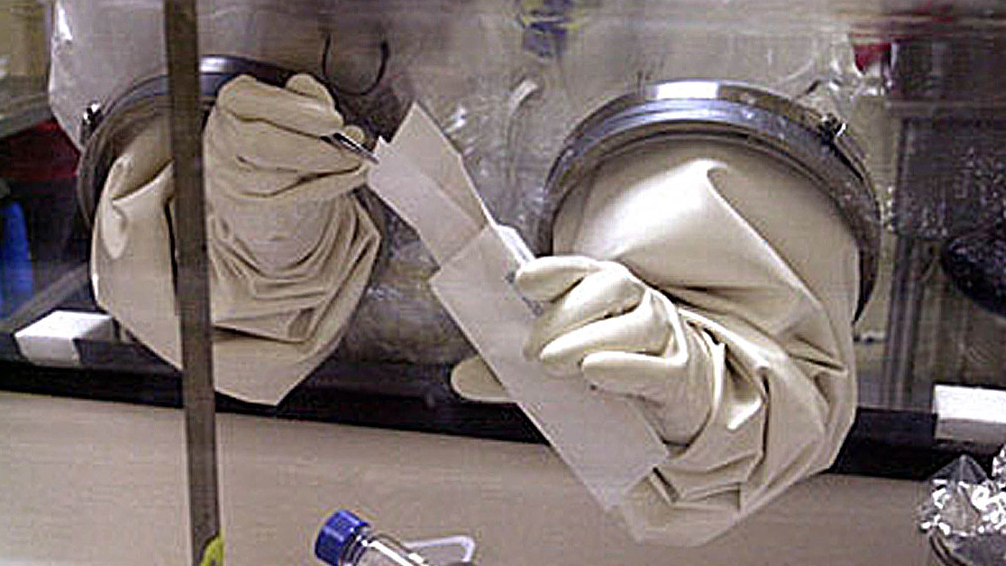

Personnel work inside the bio-level 4 lab research at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick, September 26, 2002. /CFP

Personnel work inside the bio-level 4 lab research at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick, September 26, 2002. /CFP

A stained history

Fort Detrick has been kept away from the public's eyes for over 70 years. During that period, reports suggest it has been a playground for some of the most secretive and unethical research the U.S. government has conducted.

A number of government affiliates have used the sprawling complex to conduct research on a wide spectrum of viruses and bacteria since World War II. It even operated a dirty bomb factory, producing roughly 1 million anthrax bombs, according to NPR.

During the Cold War, a cadre of rogue scientists, hired by the CIA, was alleged to have tested extreme methods on humans, in what would have been an undeniable violation of intentional law. A notorious mind-control experiment lasted 20 years and involved forced administration of psychoactive drugs, forced electroshocks, physical and sexual abuses, among other torments, according to The Devil's Chessboard, a book exposing the unpleasant history of Fort Detrick.

Failures in handling highly infectious and deadly experiment samples have also been documented at Fort Detrick.

One of the most high-profile cases was in 2001, when Bruce Ivins, a senior microbiologist working at the facility, was accused of mailing anthrax to some media outlets and government figures, killing five people. Ivins killed himself before the FBI could charge him for the attacks.

Two years later, workers unearthed less than 2,000 tonnes of hazardous waste Fort Detrick had dumped on nearby land. Vials of live bacteria and nonvirulent anthrax were detected by the local environmental protection agency. Half of 33 nearby wells were contaminated with the two agents, six were determined to be unsafe to drink, according to The Washington Post. The military claimed it had no idea about the hazards buried there.

In 2009, research at Fort Detrick was suspended because it was storing pathogens that were not listed in its database.

The list goes on.

This photo released by the FBI shows a technician at the U.S. Army's Fort Detrick biomedical research laboratory in Maryland opening a letter December 5, 2001, addressed to Senator Patrick Leahy, Democrat of Vermont, which was found in the sequestered Congressional mail on November 16, 2001. The letter was suspected of containing anthrax, based on testing conducted before the envelope was opened. /CFP

This photo released by the FBI shows a technician at the U.S. Army's Fort Detrick biomedical research laboratory in Maryland opening a letter December 5, 2001, addressed to Senator Patrick Leahy, Democrat of Vermont, which was found in the sequestered Congressional mail on November 16, 2001. The letter was suspected of containing anthrax, based on testing conducted before the envelope was opened. /CFP

The U.S. operates over 200 bio-medical labs similar to Fort Detrick around the world.

It has conducted more bio-military activities than any other country on Earth, according to Fu Cong, director-general of the Department of Arms Control at the Chinese Foreign Ministry. Loose management and lack of third-party supervision made these labs – many of which are in unknown locations – a potential threat to local residents and the environment.

Dmitry Medvedev, former Russian president and now deputy chairman of the Russian Security Council, said U.S. research in some former Soviet Union nations has "caused grave concern." The research projects lacks transparency and runs counter to the rules of the international community and international organizations, he said.

U.S. federal regulators tracked more than 1,100 laboratory incidents between 2008 and 2012 that involved bacteria, viruses and toxins that pose grave risks to people and agriculture, USA Today reported, citing a U.S. government report it had obtained.

"More than 200 incidents of loss or release of bio-weapons agents from US laboratories are reported each year," USA Today cited biosafety expert Richard Ebright as saying. "This works out to more than four per week."

Details of most of the incidents are cloaked in secrecy because of federal bioterrorism laws.

Until today, the international community is still waiting for the U.S. to respond to concerns over the highly suspicious activities in its labs, including at Fort Detrick and the University of North Carolina.