The Nord Stream 1 Baltic Sea pipeline and the transfer station of the OPAL gas pipeline, the Baltic Sea Pipeline Link in Lubmin, Germany, July 21, 2022. /CFP

The Nord Stream 1 Baltic Sea pipeline and the transfer station of the OPAL gas pipeline, the Baltic Sea Pipeline Link in Lubmin, Germany, July 21, 2022. /CFP

Editor's note: Jonathan Arnott is a former member of the European Parliament. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

The European Union (EU) is facing an energy crisis, particularly a crippling gas shortage. As the old proverb goes, "The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is now." Any number of actions could have been taken months or years ago, but there is no point in focusing on the past and trying to turn back the clock.

Every nation, in one way or another, has a long-term strategy to end reliance on fossil fuels and make use of renewable energy sources instead. Yet for the time being, each renewable source of energy has problems. The issue, bluntly, is that we do not yet have the capacity for mass storage of electricity at the scale required to store sufficient power for national electricity grids. Batteries for electric cars, storage on a small scale, have already pushed the price of lithium up by over 400 percent.

Increased use of solar power should be welcomed, but it cannot at present remove the need for gas because solar power is by nature intermittent. Wind generation suffers the same problem, but more so (peak demand tends to be on particularly hot and cold days, which happens to correlate with the times of least wind). Regardless of the rights and wrongs of the debate on nuclear power, building new nuclear plants is a long-term process. Like it or not, in the short term we are reliant on coal, oil and gas. We need to obtain it in one way or another. Western nations have to make tough choices, particularly on gas, and particularly in light of the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

In that context, the European Commission has proposed emergency legislation that require all EU countries to cut their gas consumption by 15 percent over the next two years. By using "emergency" powers, no individual country will have the power of veto over the proposal. It requires merely a qualified majority to pass: 15 of the EU's 27 nations; representing a minimum of 65 percent of the EU's population. Given huge opposition, particularly from nations in the south of the European Union, I expect significant changes and compromise. The headline and the reality will not meet, because, in reality, reducing demand is complex.

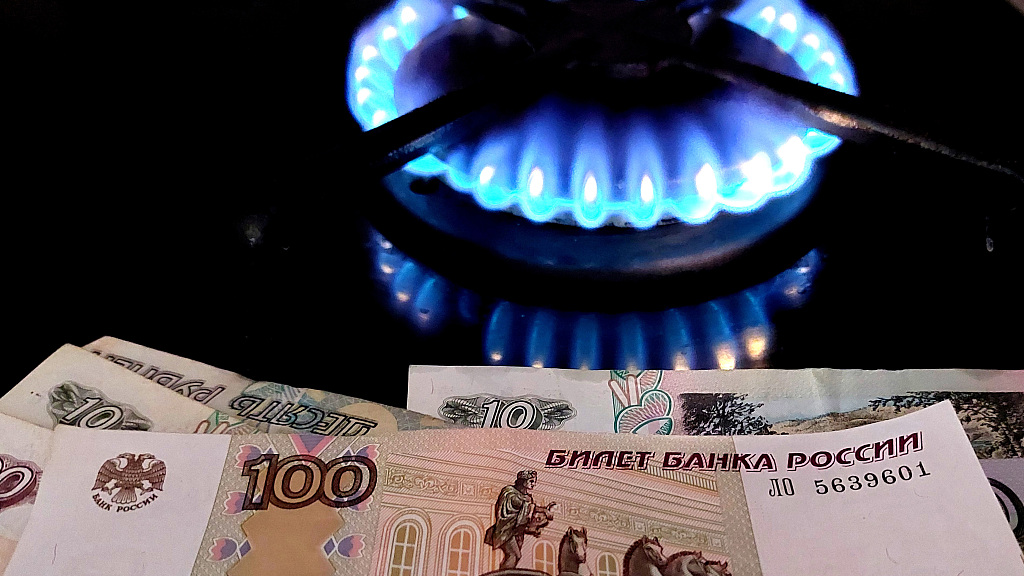

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen believes that Russia is "blackmailing" the European Union by "using gas as a weapon." However, it is a natural escalation of the proxy war between the EU and Russia. Russia is locked in a conflict with Ukraine. The EU responded by supplying weaponry, equipment and money to Ukraine while introducing economic sanctions on Russia, and consequently Russia countered with strict controls on gas exports to Europe. The EU may criticize Russia's "special military operation" in Ukraine, but it cannot reasonably criticize Russia for responding to sanctions with sanctions. The EU's packages of sanctions against Russia were designed to do the maximum damage to Russia's economy and its ability to wage war. The Russian response in that case seeks to do precisely the same. The EU weaponized economics and the financial system. Russia has weaponized gas.

The problem is that increasing supply is not easy. There are no more simple solutions for Europe to import additional gas. Everything that can be done (other than fracking – according to the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources in Germany, Europe's shale gas reserves exceed its conventional natural gas reserves) has already been done. Europe, in particular, is resistant to the use of shale gas over environmental concerns. Such concerns are understandable, at least to an extent, though for geological reasons there is a huge difference between shallow fracking in America and extraction of deeper resources in Europe.

With no easy answers, Europe has a choice to make. Russia, clearly, hopes that the EU's resolve over Ukraine will weaken if it finds itself rationing gas by the end of the year. If the current situation with Russian gas continues, even with the proposed reductions in consumption, it is likely that the EU will have to make the hard choice between its principles and its prosperity.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com. Follow @thouse_opinions on Twitter to discover the latest commentaries in the CGTN Opinion Section.)