02:49

After months of negotiations brokered by the UN and Türkiye, Russia and Ukraine agreed to restore shipments of grain and other agricultural products in the Black Sea region on July 22 by signing a grain export deal. The deal has been regarded as a positive step toward mitigating the global food crisis and preventing more people in vulnerable countries from sinking into hunger.

Both Moscow and Kyiv said they are obliged to ease the global food crisis.

However, a day after the deal was reached, Russian missiles hit the port city of Odesa, a move that has led to questions about the implementation of the deal in the coming months.

As a key shipping and transportation hub in the Black Sea region, the Odesa port is one of the three ports where Ukraine's grains resume the marine journey to enter the international market.

Maria Zakharova, Russia's foreign ministry spokesperson, said on Sunday that the missiles "destroyed a military infrastructure target" at the port in a "high-precision strike" that sunk a Ukrainian military vessel.

"Being engaged doesn't mean being married. It went well during negotiations, but it doesn't mean we will start selling grain tomorrow," said Valeriy Kotenko, a Ukrainian farmer whose income from his wheat, barley and sunflower crops has dropped by two-thirds due to increasing overland export costs in recent months.

Ukrainian officials are not feeling confident about the deal either.

"We've already begun searching for alternative routes for exporting our grain, either by truck, by train or by river," Alla Stayanova, director of the Agrarian Policy Department of Ukraine, told CGTN.

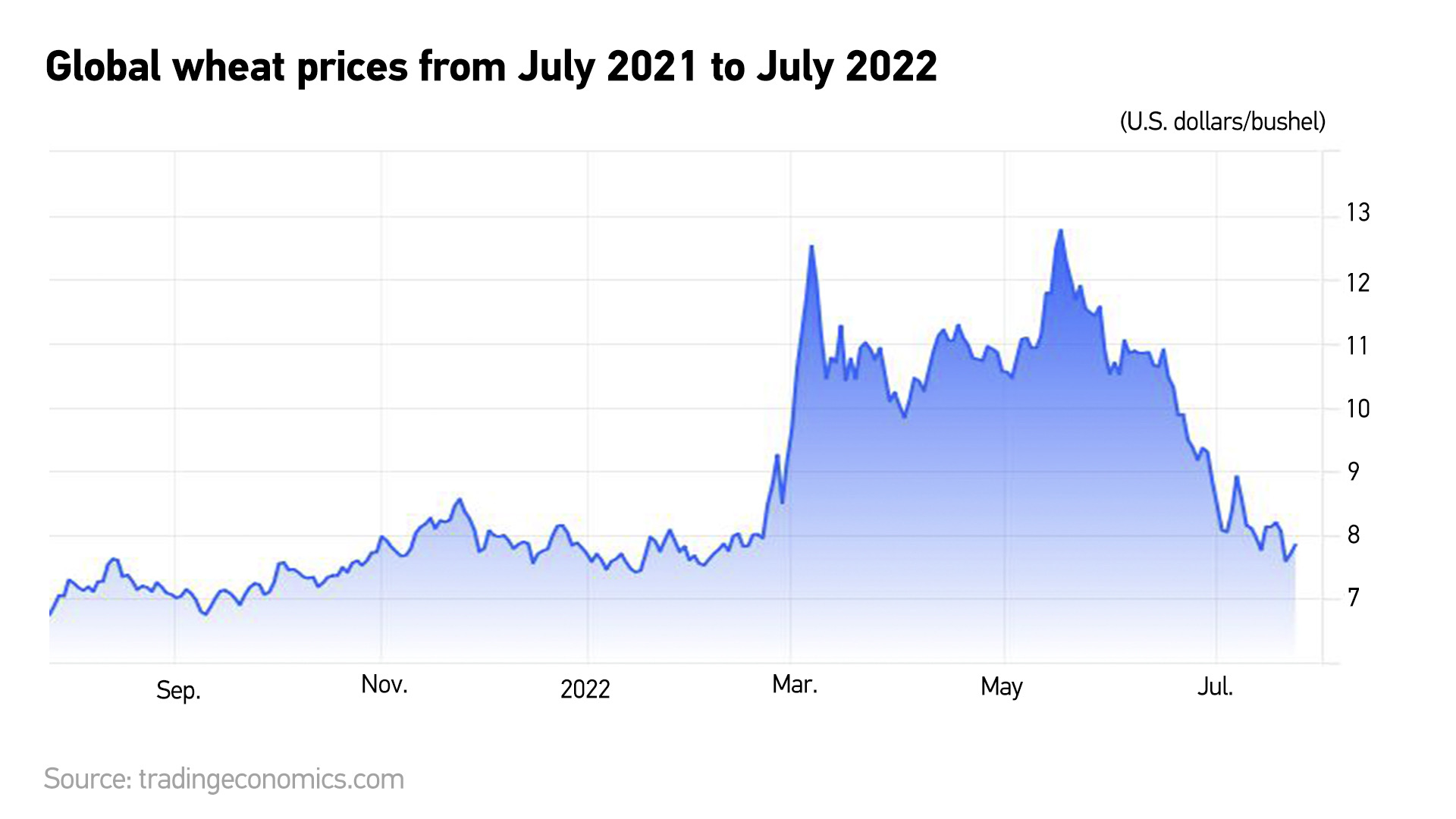

The conflict between Russia and Ukraine has halted sea shipments in the Black Sea, reducing the global supply of grain, fertilizer and energy. Coupled with supply chain disruptions caused by extreme climate events and the COVID-19 pandemic, the global grain price has seen an unprecedented rise in recent months.

After the attack, wheat prices rose 3 percent to $7.86 a bushel on Monday, regaining half of the ground lost last Friday as prices fell 6 percent after the deal was signed, according to data from Trading Economics.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy called the attack "barbarism" in his speech on the same day, saying that the Russian Kalibr missiles have destroyed the possibility of attaining the necessary dialogue.

However, the grain export deal is moving ahead despite the strike, and grains could leave the port as early as this week.

Dmytro Barinov, deputy head of the Ukraine Sea Port Authority, told CGTN that seagoing vessels and shipment operations are important for the economy of Ukraine and the world.

About 20 million tonnes of grain are stuck in the country's silos and storehouses that need to be emptied ahead of the coming harvest.

"I think the deal still has a chance, not least because Russia needs the deal as much as Ukraine needs the deal," Klaus Larres, a distinguished professor of history and international affairs at the University of North Carolina, told CGTN.

Russia's Foreign Minister, Sergey Lavrov, was on a tour in Africa and defended the strike on Odesa, denying that it held back grain deliveries.

Lavrov had said Russian exporters will meet their commitments of grain supplies in a recent press conference with Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry.

As one of the world's top importers of wheat, Egypt felt the burn of surging grain prices after Russia and Ukraine, two major wheat exporters, entered a military conflict in February. Countries such as Moldova, Lebanon and Qatar also rely on Ukraine for more than 60 percent of their wheat.

As one of the world's vital breadbaskets, Ukraine supplies more than 45 million tonnes of grain to the global market annually, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

If the conflict in Ukraine continues, an increase of some 47 million people is expected to be pushed into a state of "acute hunger," according to the World Food Programme. The steepest rises will happen in sub-Saharan Africa.

On Tuesday, representatives from Russia, Ukraine, Türkiye and the UN started working in the Joint Coordination Center, which was established to monitor all movements and inspections of ships to and from Ukrainian Black Sea ports.

"I think in a few weeks' time, we will probably see the first caravan of ships going into the port of Odesa, loading up with grain and other wheat facilities and fertilizers and leave again that port to furnish the global markets," said Larres.

(Cover image: A farmer reacts to smoke in the distance as the fighting in the Dnipropetrovsk region draws nearer to his crops, Ukraine, July 4, 2022. /CFP)

Text by Du Junzhi

Video by Hong Yaobin

Cover image and infographic by Yin Yating