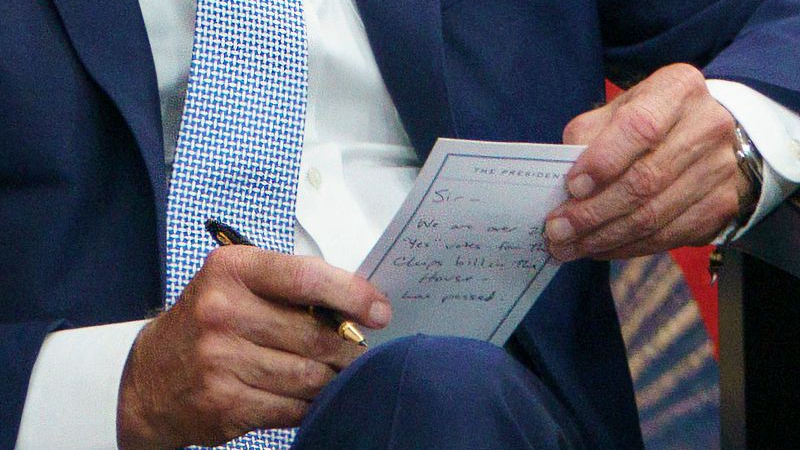

U.S. President Joe Biden holds the note given to him saying that the "CHIPS-plus" bill has received enough votes to pass the House during a meeting with CEOs about the economy in the South Court Auditorium of the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, next to the White House, in Washington, D.C., the U.S., July 28, 2022. /CFP

U.S. President Joe Biden holds the note given to him saying that the "CHIPS-plus" bill has received enough votes to pass the House during a meeting with CEOs about the economy in the South Court Auditorium of the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, next to the White House, in Washington, D.C., the U.S., July 28, 2022. /CFP

Editor's note: Bradley Blankenship is a Prague-based American journalist, political analyst and freelance reporter. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

U.S. President Joe Biden will sign into law the so-called CHIPS and Science Act on August 9, opening the door for over $50 billion in funds earmarked for developing the U.S. domestic semiconductor industry in the face of ongoing shortages. The legislation is also intended to ramp up trade competition with China and further decoupling between the two economic giants.

I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but this legislation will be a disaster. And there are a number of reasons, some rather straightforward and others that require some logical steps to understand.

The Cato Institute published analysis to offer seven reasons to oppose new semiconductor subsidies in December 2021, since the shortages should self-limit soon. The report estimated that it would be midway through this year, but it's dragging longer as we see, which would mean that any subsidies would be an outright waste.

Additionally, the semiconductor industry is highly cyclical. There's been a supply shortage – because the business cycle was disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and new orders were delayed, causing supply bottlenecks after the economies have resumed back to normal. The chip shortage is a narrow market failure and not a long-term supply chain risk; at least not any more than other industries.

Accordingly, the subsidies could disrupt the delicate cycle that exists in the market, by creating overcapacity. It could lead to increased trade conflicts – becoming a more pronounced risk when other large economies, such as the EU and Republic of Korea, are implementing similar subsidies.

Trade wars are inherently destabilizing for economies causing huge inflationary pressures that's the highest-in-a-generation. The subsidies can be a drag on innovation, as the Cato Institute notes was the case in a memory chip dispute in the 1980s and 1990s between the U.S., Japan and the Republic of Korea.

A photo of a semiconductor chip. /CFP

A photo of a semiconductor chip. /CFP

In fact, Biden's comments today sound eerily similar to President Ronald Reagan.

"The health and vitality of the U.S. semiconductor industry is essential to America's future competitiveness," Reagan said while slapping tariffs on Asian competitors. "We cannot allow it to be jeopardized by unfair trading practices."

Another immediate issue of subsidizing the domestic semiconductor industry and, in general, moving supply chains to the United States is that they don't work. There's a hypothetical discussion about supply shortages should Beijing choose to cut off trade to its largest trade partner (and thus largest stream of revenue), the United States. But there are supply shortages right now from wholly domestic supply chains.

The ongoing infant formula shortage is an example. The shortage was spurred by COVID-19 pandemic-induced supply disruptions and a recall of its baby formula produced by Abbot Labs, which produces some 40 percent of the country's domestic supply. The problem was compounded by import restrictions and high tariffs on imported formula, which explains why other countries won't ship formula to help struggling U.S. mothers.

The most notable recent example of a supply shortage – one that is literally starving babies – is caused by a lack of competition and counter-intuitive trade policy. If we already know that this strategy doesn't work and we already know that American monopolies are unreliable in delivering goods, then what sense does it make to repeat this?

There is nothing in the CHIPS legislation that specifies any sort of pro-competition fund allocation and it appears taxpayer money will go to large-tech monopolies. These companies have their bottom lines at heart and not the well-being of American consumers, and so the U.S. will be awash with chips – rather it just means supply chains will entrench their respective domestic monopolies and become more unreliable.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com. Follow @thouse_opinions on Twitter to discover the latest commentaries on CGTN Opinion Section.)