Editor's note: Sudeshna Sarkar is a Beijing-based journalist and editor of a dozen books on China's culture, economy and political system.The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily those of CGTN.

It's been an eyeopener – as well as a study in contrast – to watch the reactions to Queen Elizabeth's death and the end of an era in China and outside China, mostly in the United States.

While leaders cutting across political allegiances paid tribute to a monarch who was "one constant" for seven decades in a dizzyingly changing world, there have been some extraordinary reactions as well.

One that is still reverberating is the tweet by a modern language professor of the Carnegie Mellon University in Pennsylvania, saying, "I heard the chief monarch of a thieving raping genocidal empire is finally dying. May her pain be excruciating."

While the university distanced itself from the comment, there are both waves of condemnation by people demanding the professor be sacked and support by those who say the anger justifiably stems from Britain's support for the Nigerian federal government in the 1960s, when it fought against a secessionist movement.

Another controversy was created by a New York Times article by Harvard professor Maya Jasanoff, "Mourn the Queen, Not Her Empire," in which she wrote, "We should not romanticize her era. The queen helped obscure a bloody history of decolonization whose proportions and legacies have yet to be adequately acknowledged."

In sharp contrast, despite the two Opium Wars fought between China and Britain that resulted in national humiliation for China, territorial loss and a blow to the economy, the Chinese media has been statesmanlike. Instead of resurrecting the past, they have focused on the news of the death and the ensuing changes, and Queen Elizabeth's own associations with China, described with affection.

Social media users from Hong Kong, which was ceded to Britain as a result of the defeat in the Opium War till it was regained in 1997, have also looked beyond past wrongs to focus on a feeling of kinship. Hong Kong resident Vincent Lam wrote on Facebook, "My grandmother who raised me always spoke of the 'boss lady', I heard about her so much she felt like family ... Today it's like a family member passed away."

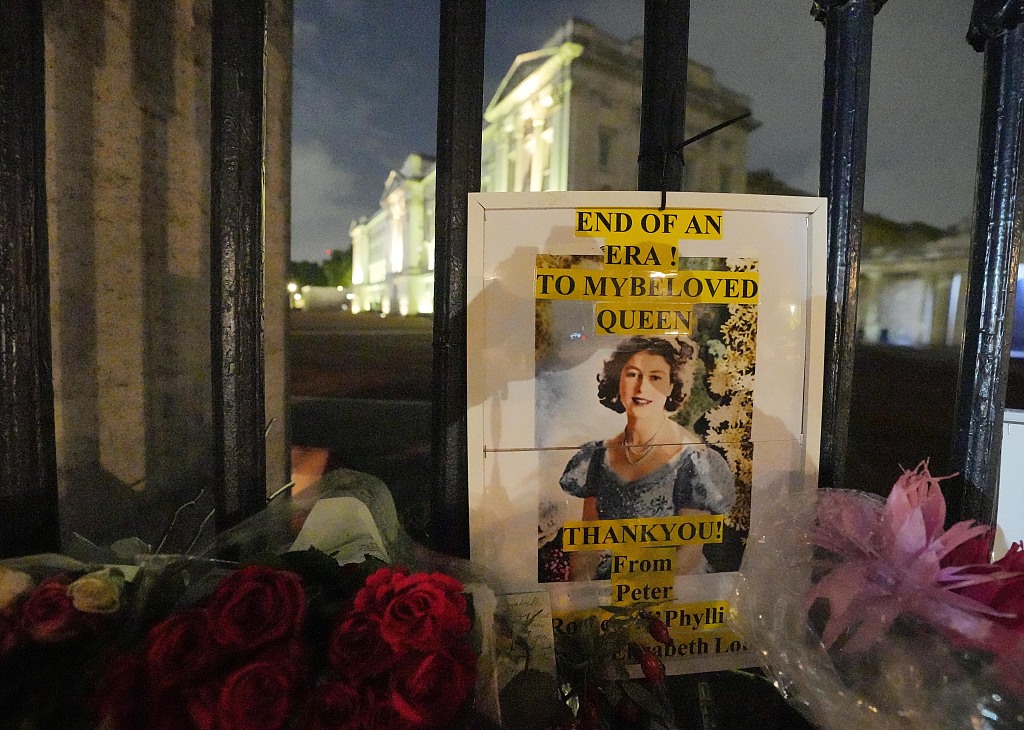

A picture of Queen Elizabeth II is set with flowers in front of Buckingham Palace in London, UK, September 9, 2022. /CFP

A picture of Queen Elizabeth II is set with flowers in front of Buckingham Palace in London, UK, September 9, 2022. /CFP

While Queen Elizabeth II was the first British monarch to visit the Chinese mainland – in 1986 – one of her ancestors had sent feelers to China centuries earlier and it remains one of the enduring historical anecdotes between the two countries.

In 1602, George Waymouth, the captain of two small ships funded by the British East India Company, set sail for China from Ratcliff in England, carrying a letter. It was from Queen Elizabeth I, her distant cousin from a different era sharing a common ancestor. The letter was addressed to the "Emperor of Cathay" – who would have been the Wanli Emperor of the Ming Dynasty at that time, and it sought to establish trading ties. While the letter was in Elizabethan English, there were translations in Latin, Spanish and Italian as well.

But Waymouth never reached China and the letters somehow ended up in a bin in Lancashire, from which they were discovered by a farmer. They finally made their way to China in 1984, when a British archivist presented the Chinese authorities with a colored photograph of the documents. Two years later, Queen Elizabeth II also brought a copy of the letter and in her meeting with Deng Xiaoping, the architect of China's reform and opening up, made a joking reference to the improvements made in cross-border postal delivery since then.

While her successor, King Charles III., has been to Hong Kong but not to the Chinese mainland, he has different links with Beijing. At COP15, the UN Biodiversity Conference hosted by China in Kunming last year, he gave the opening address via video link, where he mentioned with pride the School of Traditional Arts' China center. Operated by the Prince's Foundation, it was opened in Suzhou in 2018, and offers a one-year course in traditional arts and culture. But the objective goes beyond that. It hopes that the students will discover through the medium of a craft "that beyond the surface of things lies a universal natural order and they are part of that natural order."

Now King Charles III.' Sustainable Markets Initiative, started in 2020 to help the private sector run sustainably, has opened a China Council in Jiangxi in southeast China.

His son and heir to the throne, Prince William, has already been to the mainland. During his official visit in 2015, he met President Xi Jinping and the two were reported to have discussed wildlife protections, as well as football.

The ties with the royal family remain important for several reasons. The UK's new Prime Minister Liz Truss has assumed office with some anti-China baggage and it needs time to assess if that was just anticipated election rhetoric or if she is really serious about taking measures against China and Chinese businesses. In this time of new beginnings and uncertainties, the long association with the royal family remains a constant in China-UK ties.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com. Follow @thouse_opinions on Twitter to discover the latest commentaries in the CGTN Opinion Section.)