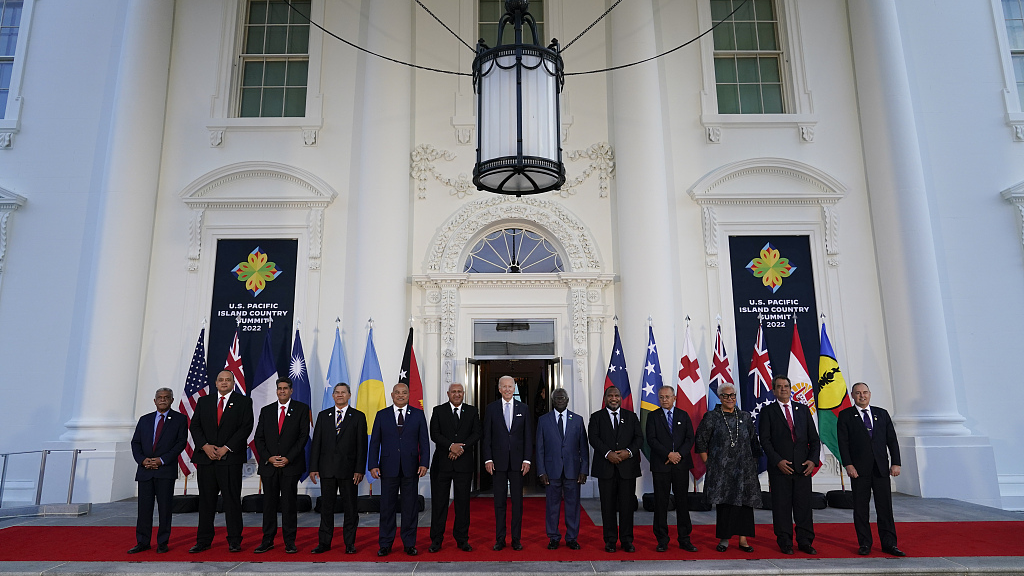

U.S. President Joe Biden, center, poses for a photo with Pacific island leaders on the North Portico of the White House in Washington, U.S., September 29, 2022. /CFP

U.S. President Joe Biden, center, poses for a photo with Pacific island leaders on the North Portico of the White House in Washington, U.S., September 29, 2022. /CFP

Editor's note: Abu Naser Al Farabi is a Dhaka-based columnist and analyst focusing on international politics, especially Asian affairs. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily those of CGTN.

"Long time no see"— the United States has recently begun a flurry of "patting on the back" diplomatic efforts to rekindle itself as a credible partner to the Pacific island nations. Last week, the Joe Biden administration hosted a number of Pacific leaders in Washington for the "U.S.-Pacific Island Summit"— a first-of-a-kind meeting for which the U.S. has invited many Pacific leaders to the White House.

However, that the U.S. sense of urgency to re-emphasize its engagement in its take-for-granted maritime "backyard" has stemmed from its intent to address the islanders' existential crisis appears highly questionable. As per the official narratives and experts' views, the U.S. reassertion into the region is reactionary in nature and a cut-and-dried zero-sum approach to undermine China's presence in the Pacific region.

Sake of self-interest

On the eve of the summit, while addressing a Carnegie Endowment for International Peace event, the U.S. National Security Council's Indo-Pacific coordinator and one of Biden's most senior foreign policy advisers, Kurt Campbell, said, "It is not just one or two meetings — this is a very sustained effort that will involve almost all the key players in the U.S. government who have interests in the Indo-Pacific." He added that rivalry with China is behind renewed U.S. attention to the Pacific island countries.

Moreover, U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken, during his address to Pacific leaders at the summit, hinted at the core driver of its sudden diplomatic double-down, by saying the U.S. would work with islanders on "preserving a free and open Indo-Pacific" — a veiled reference to its China-containment strategy.

U.S. secretary of state Antony Blinken arrives during the "U.S.-Pacific Island Country Summit" at the State Department in Washington, U.S., September 29, 2022. /CFP

U.S. secretary of state Antony Blinken arrives during the "U.S.-Pacific Island Country Summit" at the State Department in Washington, U.S., September 29, 2022. /CFP

To sum up, the core rationale behind the U.S. Pacific is all based on its "great power competition framework" crafted to contain China — to that end, enticing countries into its geostrategic bandwagon by pledging commitments far more general and void of any specific policies and promises.

Promise and betrayal

One day after fierce "diplomatic discord," according to the Guardian, among the Pacific leaders over the draft declaration proposals, a Declaration on U.S.-Pacific Partnership came at the end of the unprecedented two-day summit in Washington. With lofty goals and hefty intangible principles, the declaration consists of a host of U.S. commitments ranging from bolstering Pacific regionalism to tackling the climate crisis to maintaining peace and security in the region.

But the questions over whether the U.S. could drive those commitments to the substantive and long-term benefits to Pacific island countries are widely asked, given its toxic foreign policy legacy in the region — promising a whole lot when necessary, delivering far less on those, and discarding when losing its usability.

There is a widespread perception among the Pacific island countries that the U.S. is highly unreliable — a widely shared regional belief about the U.S. that has been cemented by its diametrically different treatments of the islanders during and after the Cold War. As the professor of history in the Asian Studies Program at Georgetown University, Patricia O'Brien said, "America premised their whole efforts in the Pacific on [Cold War] geostrategic competition, and once that [Soviet] threat was gone, America didn't see the reason to be in the Pacific anymore."

Throughout the Cold War, it fought against the Soviet Union, the United States had treated those island countries — remote, prone to natural disasters and lagging in economic development — as its military backyards. But immediately after the end of the Cold War, it withdrew its big promises to court their support, such as closing down embassies and discontinuing the Peace Corps agency through which it provided its development assistance, eventually discarding the region into a decades-long diplomatic afterthought.

The case is strikingly true regarding its current frenzy Pacific foreign policy posture. Its re-engagement drive to woo Pacific islanders is reactionary rather than one aroused from its so-called goodwill to establish an enduring partnership for the benefit of the region. The U.S. would never have turned its eyes to Pacific islanders, let alone on their miseries if China had not made any diplomatic inroads into the region and had not been framed as America's "strategic rival."

The U.S. is here to counter China, not to engage with them for their own sake. If history is any guide to the future, the "Pacific Partnership" one being trumpeted by the U.S. today will at best be a "temporary pivot" other than one that will be enduring and substantive.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com. Follow @thouse_opinions on Twitter to discover the latest commentaries in the CGTN Opinion Section.)