Former U.S. Vice President Al Gore speaks during a session at the COP27 UN Climate Summit, Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, November 9, 2022. /CFP

Former U.S. Vice President Al Gore speaks during a session at the COP27 UN Climate Summit, Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, November 9, 2022. /CFP

Editor's note: Gary Yohe is the Huffington Foundation Professor of Economics and Environmental Studies, Emeritus, at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. He served as convening lead author for multiple chapters and the Synthesis Report for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change from 1990 through 2014 and was vice-chair of the Third U.S. National Climate Assessment. The article reflects the author's views and not necessarily those of CGTN.

Just for the record, because some have already suggested it, the convening of the 27th Conference of the Parties (COP27) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Sharm El-Sheikh is not a reason to relitigate the need for climate action and "climate summits." To answer deniers' hierarchy of arguments against these annual conferences, the planet is warming, human activity is largely to blame, extreme events are increasingly costly and more frequent, adaptation helps but never completely covers the damage, and it is not too late to do something about it. And so, moving onto COP27 is imperative.

In fact, the UNFCCC ship recognizing climate risk has already sailed. So live with it. The meetings are a fact of life in the fall of each and every calendar year.

In Article 2 of the UNFCCC, the Parties committed themselves to preventing "dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system." Article 4 commits them to cooperating "in preparing for adaptation to the impacts of climate change." Article 4 also commits developed country Parties to helping developing country Parties to meet not only their obligations under the treaty, but also to support their efforts to cope with their own specific versions of climate change risk. The question is not, therefore, "Should there be a COP27?" It is, instead, "What are they going to accomplish?" in the current chaotic climate.

We know the broad strokes of their agenda: fully underwriting the Adaptation Fund, solidifying coverage of residual damages and losses, and updating mitigation pledges in their own best interest in the now more complicated chaos of the current geopolitical disarray. Equity will be a cross cutting focus of their deliberations across these topics. But how will they evaluate progress (or lack thereof) from past experience and into anticipated futures to allocate current and future efforts? What is their decision metric?

We know that "iterative risk management" will be the lens through which they assess current and prospective needs. How do we know that? Because the same group of signatory countries approved, by consensus, the following language word by word:

"Responding to climate change involves an iterative risk management process that includes both mitigation and adaptation and takes into account climate change damages, co-benefits, sustainability, equity, and attitudes toward risk."

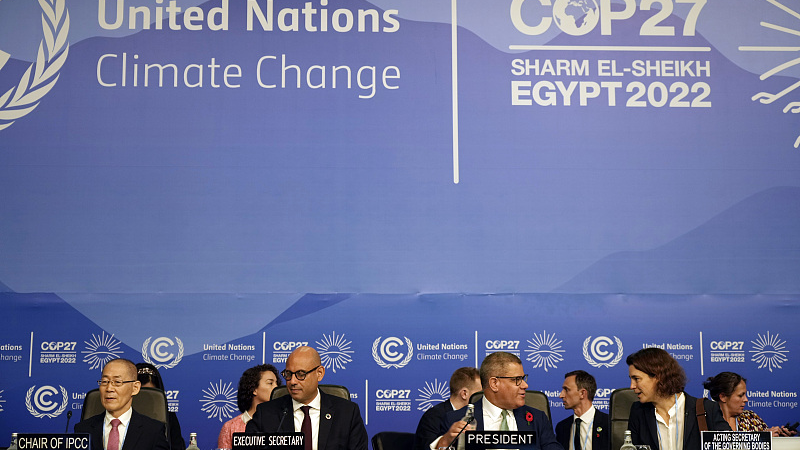

L-R: Leaders of the UN climate conference, Dr Hoesung Lee, chair of the IPCC, Simon Stiell, UN climate chief, and Alok Sharma, president of the COP26 climate summit, at the opening session at the COP27 UN Climate Summit, November 6, 2022. /CFP

L-R: Leaders of the UN climate conference, Dr Hoesung Lee, chair of the IPCC, Simon Stiell, UN climate chief, and Alok Sharma, president of the COP26 climate summit, at the opening session at the COP27 UN Climate Summit, November 6, 2022. /CFP

Why bring the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to the table? Because the IPCC was established in 1988 by the United Nations Environmental Program and the World Meteorological Organization to provide the scientific basis supporting what they anticipated would be global negotiations about climate change. Its reports were prohibited by charter from being policy prescriptive, but they could be policy relevant. In that role, they became the scientific basis for UNFCCC negotiations at the very inception of the Framework. The assessed science was to be accepted to the point that its findings (including confidence statements) were non-negotiable between IPCC reports. And so, consensus acceptance of the words above means that they describe how the COPs frame their deliberations.

As COP27 begins, it is important to note the significance of their adopting an "iterative risk management" approach. The COP structure already handles the "iterative" part. The Parties meet in the fall of every calendar year to assess progress and make "mid-course corrections" as needed. Their acceptance of risk as the metric of concern has much more significance than that.

Risk is the combination of the consequences of a particular event and its likelihood. The Parties, in accepting risk as their decision metric, indicated that they wanted to be informed about high risk possibilities. A high risk assessment can be supported by medium confidence in a finding that portends high consequences. That much is obvious. Less clear in the common vernacular is that a high risk assessment can also be supported by low confidence in a finding that portends extremely damaging consequences.

It follows that the IPCC's reporting low likelihood and very high consequence events in its assessments is not "fear-mongering." It is the product of deliberate efforts to meet the expectations of its clients – the 198 Parties to the UNFCCC.

Take, for example, the potential collapse of the Thwaites glacier in western Antarctic sometime in the near-term future. Indeed, that future may already be baked into the dynamics of the Antarctic climate. Or maybe not. The observed acceleration of glacial migration could stop completely at any time in the next 20 years. Were it to progress to a complete collapse, though, it would suddenly produce up to a foot of additional sea level rise around the world over a decade or two at an unknown time in the future. Confidence that this will happen is low at this point in time, but the consequences would not just be extremely large. For countless communities around the globe, it would be catastrophic.

COP27 knows this, and this knowledge will certainly add to the urgency with which they work towards reducing emissions and the way that they direct the Adaptation Fund towards investing in protecting the world's coastlines or facilitating retreat where all hope is lost.

It is important to note, in passing, that the melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet was in the same low-likelihood high-consequence category at the turn of the century - lots of potential sea level rise over a long period of time with a low likelihood of something noteworthy in the near term. By 2022, though, recent data had shown that the pace of melting had accelerated irreversibly. As a result, there is now a medium to high confidence that damaging ice melt and associated increased sea level risk will eventually produce severe coastal consequences earlier than previously expected.

It will be interesting to see how these threats to coastal communities and ecosystems around the world factor into COP27 deliberations about the Adaptation Fund and their cross-cutting theme of equity. Who are the world's most vulnerable people? Poor people who live close to large bodies of water.

Nothing is static in this domain. Get used to it.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com. Follow @thouse_opinions on Twitter to discover the latest commentaries in the CGTN Opinion Section.)