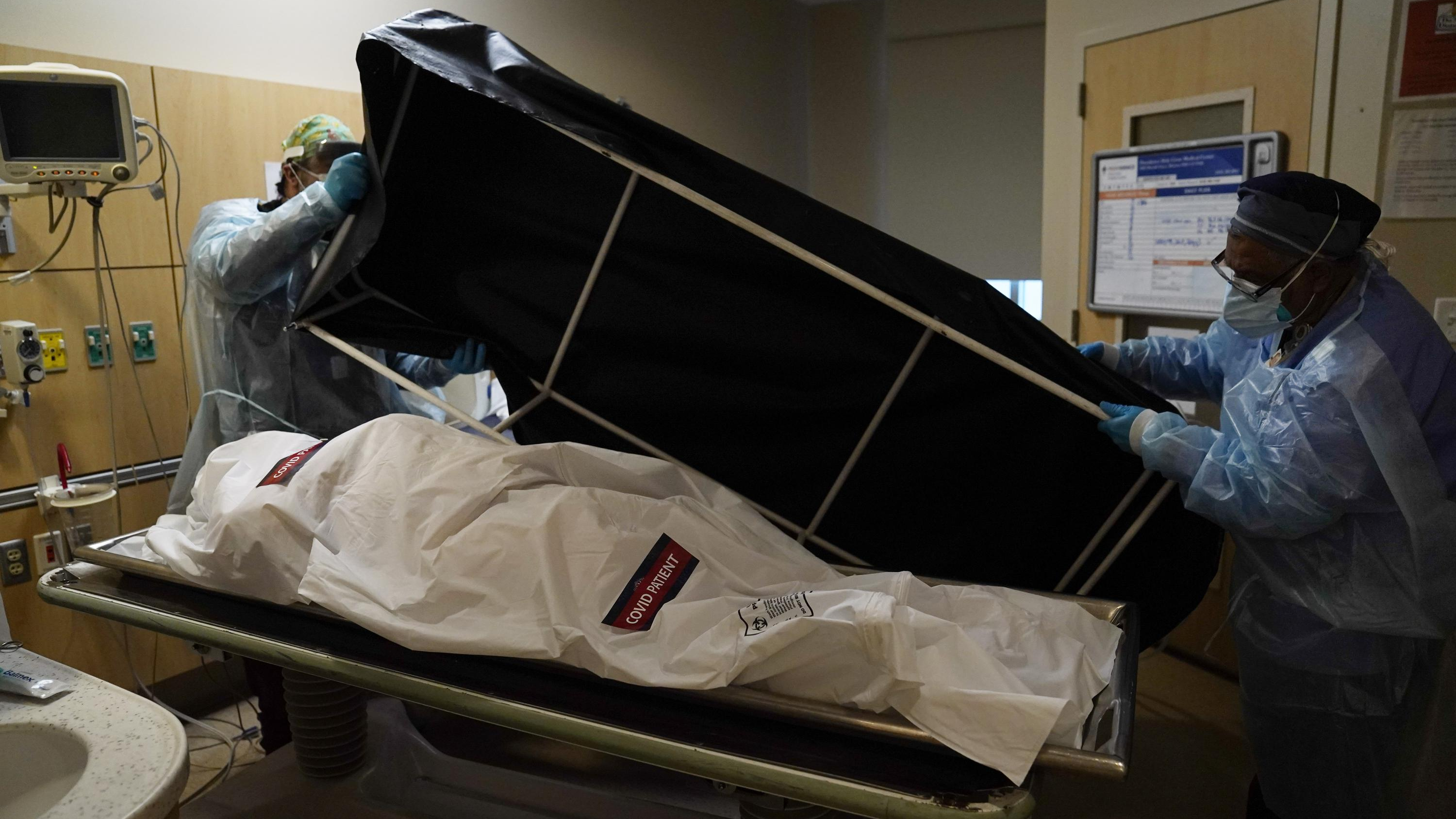

Transporters prepare to move the body of a COVID-19 victim to a morgue at Providence Holy Cross Medical Center in the Mission Hills section of Los Angeles, California, U.S., January 9, 2021. /AP

Transporters prepare to move the body of a COVID-19 victim to a morgue at Providence Holy Cross Medical Center in the Mission Hills section of Los Angeles, California, U.S., January 9, 2021. /AP

The number of COVID-19 cases in the United States surpassed 100 million on Tuesday, according to data compiled by Johns Hopkins University.

The U.S. remains the nation worst hit by the pandemic, with the world's most cases and deaths, accounting for more than 15 percent of the global caseload and over 16 percent of the global deaths.

"We have seen COVID cases go up. We've seen hospitalizations go up. Deaths are just starting to rise," Dr. Ashish Jha, the White House's pandemic response coordinator, told the media last week.

Looking back at the past three years, a story of politics and race emerges.

Race gap

When Navajo Nation resident Dawn Lynn Nez was diagnosed with COVID-19 in October last year, she had no other option but to lock herself inside the house. Then a single mom of five kids, she lacked food and medicine, not to mention medical assistance.

"I was so scared, I was so devastated, especially for my little ones," Nez told CGTN.

In the initial stage, ethnic minorities in the U.S. suffered disproportionately due to persistent shortages in social and medical resources, which existed long before the pandemic. Federal and state data show that Black, Asian, Native American and Hispanic populations were far more likely to get infected and die from COVID-19 than Whites.

According to an analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation, COVID-19 related death rates among Black people, American Indians and Alaska Natives were about twice as high as the rate for White people as of August 2020.

As the virus quickly spread in minority-concentrated communities and neighborhoods, some studies have found the care minorities received in hospitals or the lack of it contributed to poorer outcomes. Rubix Life Sciences, a Boston-based data firm, found that African Americans with symptoms such as coughing were less likely to receive coronavirus tests that became short in supply due to the skyrocketing cases. But the differences don't just stop there.

African American patients were also more likely than Whites to receive an older, less expensive version of blood thinner linked to higher mortality from COVID-19, according to a study using data from the Society for Critical Care Medicine published in 2020. Blood-thinning drugs became a common treatment in Western nations early on in the pandemic as many patients developed clots.

Researchers have since questioned whether some doctors chose the older product for minority patients because new drugs were being tested overwhelmingly on White patients.

The first patient enrolled in Pfizer's COVID-19 coronavirus vaccine clinical trial receives an injection at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, U.S., May 4, 2020. /AP

The first patient enrolled in Pfizer's COVID-19 coronavirus vaccine clinical trial receives an injection at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, U.S., May 4, 2020. /AP

COVID-19 remains political

By the end of last year, the pattern of COVID-19 mortality had quietly shifted. According to an analysis by the Washington Post, gap in deaths between Black and White populations in the U.S. had narrowed and even flipped with Black rates lower than White rates since November last year, with the exception of the Omicron surge in the beginning of this year.

So, what contributed to the shift in mortality rates?

Emerging research suggests it has much to do with the increasing political polarization in the U.S., which has led to unprecedented level of fragmentation in public discourse. When it comes to the coronavirus, the American public is largely split into two camps, with most progressives believing in vaccination, as demonstrated by higher vaccination rates, while most conservatives have subscribed to the school of self-reliance.

"We're Republicans, and 100 percent believe that it's each individual's choice, their freedom," when it comes to getting a coronavirus shot, Georgia resident Hollie Wilson whose husband died due to COVID-19 told the Washington Post in January. "We decided to err on the side of not doing it and accept the consequences. And now, here we are in the middle of planning the funeral."

A recent Yale University study shows a link exists between political party affiliation and excess death rates caused by the pandemic. After examining death and voting records of over half a million people between 2018 and 2021, researchers found a higher excess death rate for Republican voters than Democratic voters, with the difference spiking after COVID-19 vaccines became widely available.

"Results suggest that the well-documented differences in vaccination attitudes and reported uptake between Republicans and Democrats have already had serious consequences for the severity and trajectory of the pandemic in the United States," the paper continued. "If these differences in vaccination by political party affiliation persist, then the higher excess death rate among Republicans is likely to continue through the subsequent stages of the COVID-19 pandemic."