As a veteran researcher and calligrapher, Xie Xiaoquan is now working at the China National Academy of Painting. "In the olden days, Chinese artists would always create a piece of calligraphy after having a get-together, like the 'Preface of the Orchid Pavilion,' for instance," said Xie. The situation is quite different today.

07:57

People practice the art as a profession, he noted. "I think it's more touching when artworks are expressed truthfully, from the bottom of our hearts."

With more than two decades of experience working at the National Museum of China, Xie is well aware of how the many cultural relics he encountered that nourished his artistic growth, sometimes in barely perceptible ways, "when I pick up the brush to paint, something magical flows naturally from the tip of my brush at any time," he explained.

"In my opinion, calligraphy plays a very special role in the historical development of Chinese culture. Since the birth of the Chinese characters, or even before, these kinds of engraving symbols have had an innate aesthetic power. Therefore, Chinese calligraphy will always be linked to the development of Chinese culture," he said.

From oracle bones and bronze inscriptions to official or regular script and Chinese stone rubbings, calligraphy represents an evolution of these aesthetic forms. It also serves as an important cultural code in Chinese civilization. "Especially now, we should say we are more and more aware of its importance in Chinese cultural heritage," Xie said.

Xie Xiaoquan practices calligraphy. /CGTN

Xie Xiaoquan practices calligraphy. /CGTN

Besides calligraphy, rubbings, and epigraphy are key means of studying and inheriting Chinese culture. Many historical events, including King Wu's conquest over King Zhou, were recorded in inscriptions found on bronze-ware artifacts. "So rubbing was a very effective way for ancient Chinese to learn and study, duplicate and preserve these historical sites and evidence," Xie said, noting the fact that many original tablets have disappeared, yet the rubbings remain. The technique of ink rubbing has existed since the Tang Dynasty (618-907), but it matured during the Song Dynasty (960-1279).

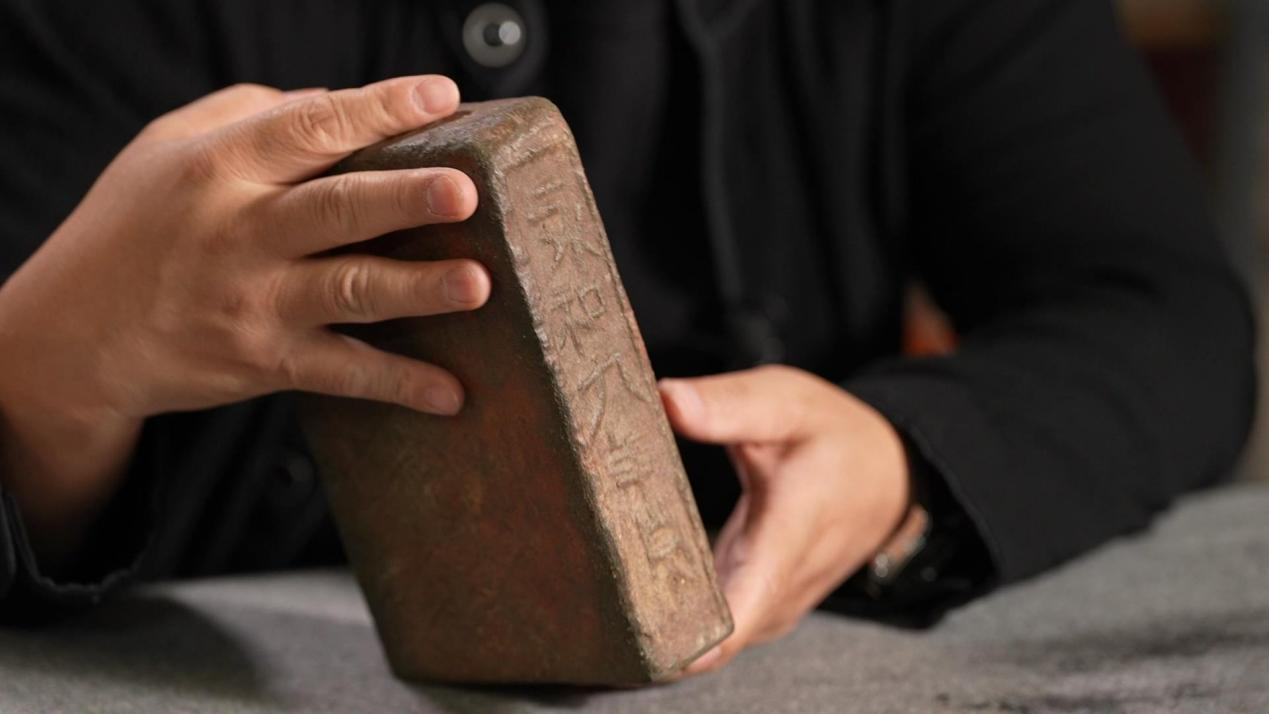

In fact, a large number of pottery and ceramic styles, bricks, and tiles fall into this category of epigraphy, a complex subject. During the interview, Xie displayed a brick engraved with an important title from the ninth year of Emperor Yonghe (353 CE).

"That's when Wang Xizhi wrote the 'Preface of the Orchid Pavilion,' so it was an important year in the history of calligraphy," he said.

Xie Xiaoquan displays an ancient brick. /CGTN

Xie Xiaoquan displays an ancient brick. /CGTN

When it comes to cultural inheritance, Xie has his own opinion. "Tradition and innovation, in my mind, indicate a kind of causality," he said. "No tradition, no innovation. I disagree with the kind of innovation that's completely removed from tradition. This is certainly true in the field of calligraphy. If you don't practice and imitate different kinds of traditional script forms and famous works and instead jump straight into trying to innovate, your work will be overshadowed by your lack of training."

"But of course, if you completely abide by tradition, you will never make a breakthrough," Xie added. "You need to create something innovative using tradition as a foundation. In doing so, tradition brings extra vitality."