Editor's note: Wretched City upon a Hill is a 10-part series examining the clash between America's cherished beliefs about its democracy and the jarring truth about how the system fails in practice. The seventh essay is about the prison system.

The caged birds singing for freedom to bring

Black bodies being lost in the American dream

Blood of black being, a pastoral scene

Slavery's still alive, check Amendment 13

Not whips and chains, all subliminal

Instead of 'nigga' they use the word 'criminal'

Sweet land of liberty, incarcerated country

Shot me with your Rea-gan

And now you want to Trump me

——Letter to the Free

13th is a documentary directed by African American director Ava DuVernay that examines how African Americans are still discriminated against through mass incarceration and structural injustice brought by the current American judicial and prison system. The rapper Common wrote the above song Letter to the Free for the film, calling for true liberty for African Americans.

In the "sweet land of liberty," many people still live with "chains" and go through suffering that should not exist in a modern civilization. What happens in the daily life of inmates in the U.S. tells us a different story of American liberty and democracy.

In 2015, then-U.S. President Barack Obama said in his address to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), "The United States is home to 5 percent of the world's population, but 25 percent of the world's prisoners...We keep more people behind bars than the top 35 European countries combined."

According to the Prison Policy Initiative, a non-profit organization in the U.S., about 1.9 million people in the U.S. were in prison in 2022.

What is more striking is how prevalent racial bias is in mass incarceration. Mass incarceration in the United States is inherently racialized, with a long history of disproportionately affecting and targeting Black and Hispanic Americans. This racialization of the criminal justice system is a shackle for minority groups that exacerbates social inequality in the country.

The incarceration rate in the U.S. stayed stable until the mid-1970s, when it skyrocketed as a result of changes in American laws and policies, including "tough on crime" laws, the "war on drugs," and the practice of mandatory minimum sentences and harsh sentences.

However, instead of substantially reducing crime rates, those policies created a heavy fiscal burden on the society and greater structural inequalities. These policies have hurt Black and Hispanic people so much that they have been dubbed the "new Jim Crow laws."

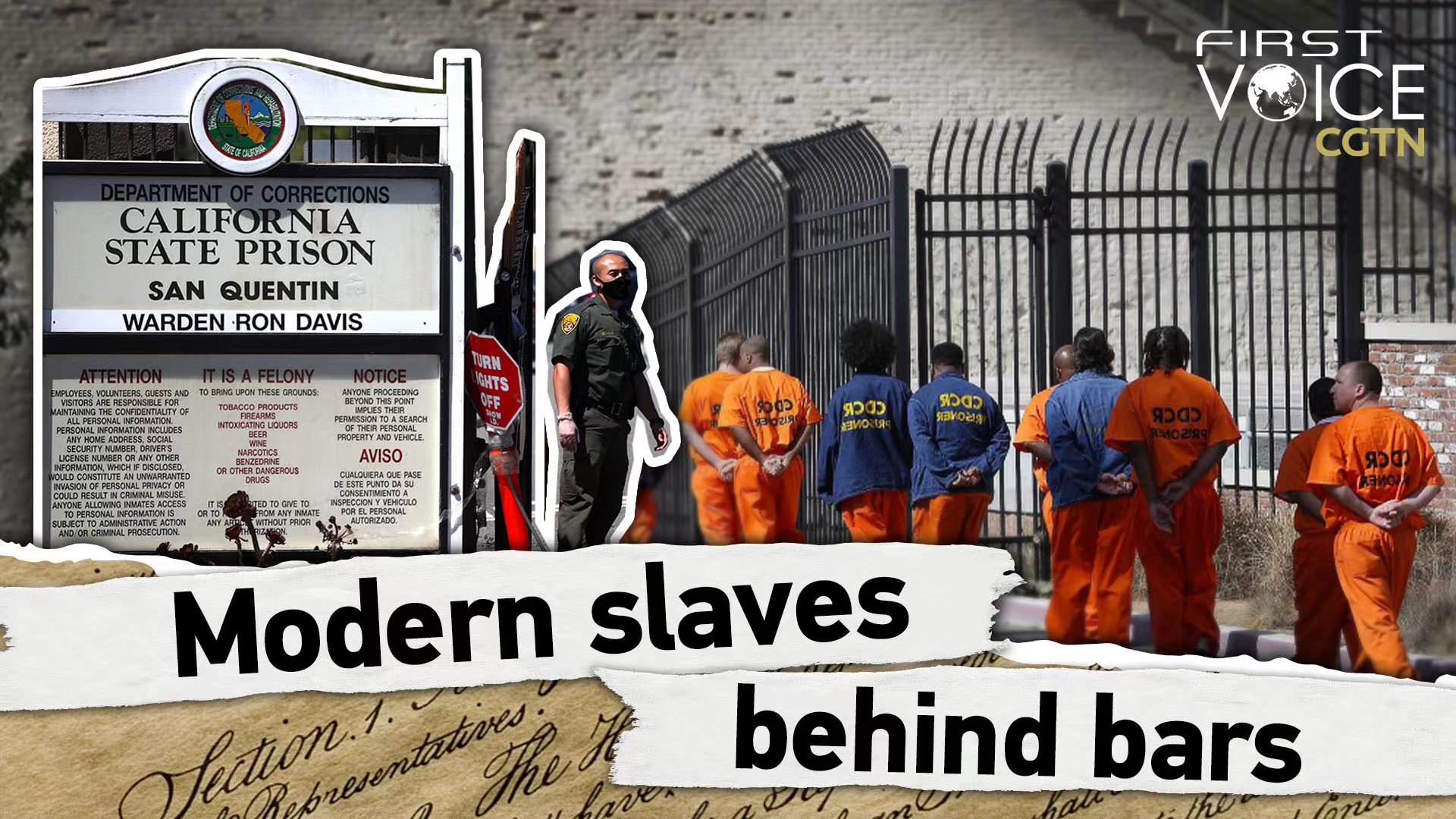

A row of general population inmates walk in a line at San Quentin State Prison in San Quentin, California, August 16, 2016. /VCG

A row of general population inmates walk in a line at San Quentin State Prison in San Quentin, California, August 16, 2016. /VCG

As the report Prison Policy Initiative released in 2022 shows, African Americans, who make up 12 percent of the U.S. population, account for 38 percent of the country's prison population. Their incarceration rate is about five times that of Whites.

The racialization of mass incarceration deepens social inequality for the Black community making it difficult for people to find stable jobs and safe housing after they are released. Their criminal records will exert a negative influence on the development of their children. Mass incarceration makes Black neighborhoods worse places to live in, thus widening the gap in economic and social status between Black and White people.

Large numbers of African American prisoners live in an environment without adequate decency and human rights protection. The U.S. is notorious for inmate abuse. Inmates may not only be subject to punishment such as beatings and solitary confinement, but also to convict leasing, forced labor, and other forms of economic exploitation. They are literally modern slaves behind bars.

About two-thirds of inmates in federal and state prisons are required to work, according to a report jointly released by the University of Chicago and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in 2022. They are under complete control of their employers and do not have minimum protection against labor exploitation or abuse. About 70 percent of inmates said that their prison labor wages could not cover their basic necessities; 64 percent were concerned about workplace safety; 70 percent had not received formal job training; and 76 percent were forced to work, or they would be punished.

Shane Bauer, an American journalist, documents how inmates in modern prisons are forced to work and exploited in his book American Prison: A Reporter's Undercover Journey into the Business of Punishment. If some prisoners refuse to work or work slowly, they may be placed in solitary confinement or denied essential items, including water and food.

Demonstrators protest against racial injustice to mark Juneteenth, commemorating the end of slavery in the United States, near the White House in Washington, D.C., the U.S., June 19, 2020. /Xinhua

Demonstrators protest against racial injustice to mark Juneteenth, commemorating the end of slavery in the United States, near the White House in Washington, D.C., the U.S., June 19, 2020. /Xinhua

Forced labor in American prisons seems out of place in the "sweet land of liberty." What is even more ironic is that it has not only long existed, but is also protected by the U.S. Constitution. In fact, the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, passed by the U.S. Congress in 1865, which marked the end of slavery in the U.S., was the legal loophole that was used to create "modern slavery."

The 13th Amendment provides that "neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction." This exception was immediately used by Southern plantation owners who developed a convict leasing industry during the Reconstruction when state governments leased (and benefited from) convicts to merchants who then forced them to work under poor conditions.

In 1883, about 10 percent of Alabama's annual revenue came from convict leasing and the share climbed to 73 percent by 1898, according to a report published on the Digital History website. The appalling consequence was that death rates of prisoners in leasing states were 10 times higher than in non-lease states.

Although convict leasing was later abolished in the U.S., forced labor in prison remains prevalent. Statistics from the Federal Bureau of Prisons show UNICOR, the federal government's correctional program, pays inmates a wage between 23 cents and $1.15 per hour (well below the average wage of U.S. workers), while the national average wage for inmates is only 13 cents to 52 cents per hour. In some government prisons in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Texas, inmates do not even get a penny for their work.

Activists rally against financial institutions' support of private prisons near Wall Street in New York City, the U.S., May 1, 2018. /Xinhua

Activists rally against financial institutions' support of private prisons near Wall Street in New York City, the U.S., May 1, 2018. /Xinhua

Huge profits from such cheap labor go to the government and private companies. UNICOR makes $5 billion annually, according to its website. CoreCivic, the second-largest community corrections company in America, earned $1.85 billion in 2022 alone. To keep making money, private prison companies include "incarceration quotas" in their deals with federal and state governments.

Private prisons also lobby lawmakers. CoreCivic, for example, contributed huge sums of money during the 2022 elections and spent $1.84 million on lobbying, according to Open Secrets website.

As the lyrics of Letter to the Free goes, "Prison is a business, America's the company, investing in injustice, fear and long suffering." Forced labor exists in both government and private prisons in the U.S., and no matter how lofty the goals of their correctional programs may sound, they are ultimately for profit.

The racialization of mass incarceration, structural inequalities, and inmate abuse and forced labor in American prisons speak volumes about the hypocrisy of American democracy and liberty. Perhaps "America's moment to come to Jesus" is approaching, but there is still a long way to go.

Despite increasing calls for prison reforms from human rights activists and NGOs as well as judicial reform efforts by the Biden administration, the road to meaningful reform is bound to be bumpy because of the high profits of the prison industry and the interests complex of the public and private sectors.

(The author, Yu Feng, is an assistant research fellow at the Institute of American Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com. Follow @thouse_opinions on Twitter to discover the latest commentaries in the CGTN Opinion Section.)