Editor's note: Wretched City upon a Hill is a 10-part series examining the clash between America's cherished beliefs about its democracy and the jarring truth about how the system fails in practice. The eighth essay is about lynching in America.

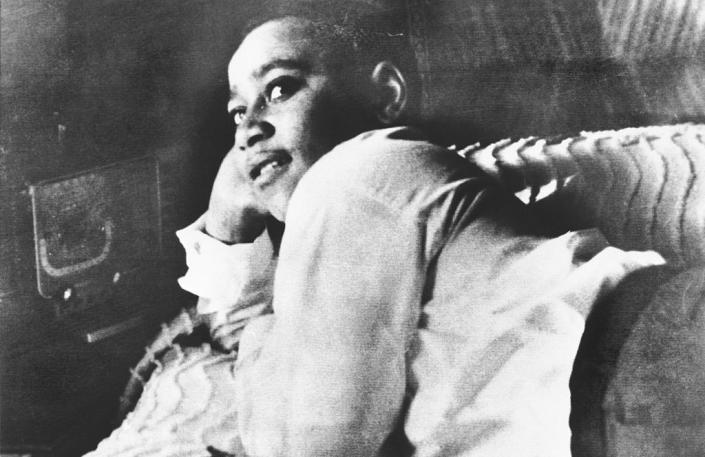

Till, an American film released in 2022, is based on a true story. In 1955, Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy from Chicago, was brutally murdered while visiting his relatives in Money, Mississippi. Accused of whistling at a White woman, he was kidnapped and killed by the woman's husband and brother, and then thrown into the Tallahatchie River.

Three days later, his mutilated body was discovered. The face was barely recognizable. His mother chose to have an open-casket funeral to expose the brutality and demand justice for him. When photographs of his corpse appeared in magazines, the nation was shocked.

Till was one of the thousands of African-Americans who died from lynching, reflecting a brutal part of American history.

The word "lynching" is popularly believed to be derived from the name Charles Lynch, a justice of the peace in Virginia, who privately adjudicated, sentenced and hanged loyalists to the British Empire during the American Revolution. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) defines lynching as the public killing of an individual without due process. Lynchings were often carried out by cruel and lawless White mobs. The word typically evokes images of Black men and women hanging from trees in the South, but lynchings involved other extreme brutalities, such as torture, mutilation, decapitation, and desecration. Some victims were burned alive.

"Southern trees bear a strange fruit.

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root.

Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze.

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees."

The lyrics from the song Strange Fruit were written by Abel Meeropol and first recorded in 1939 by Billie Holiday, a famous Black singer. There is a tragic story behind it. Two Black men accused of raping a White lady and killing her boyfriend were lynched on August 7, 1930 in Marion, Indiana. The White mob took the two men from jail and hanged them in front of more than 10,000 White people. Crowds enjoyed the brutality. Photographs of the lynching circulated and Abel Meeropol wrote the song after seeing one. Strange Fruit became an anthem for Black protest.

The exact number of lynching victims throughout American history remains unknown. The Washington Post reported in 2022 that about 6,500 Americans were lynched in the 80 years prior to 1950, with the majority being Black. A 2017 report from The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting racial reconciliation, documented more than 4,084 lynchings of Black men in 12 southern states of the U.S. from 1877 to 1950. The highest rates of lynchings were found in states such as Mississippi, Florida, Arkansas, and Louisiana.

Emmett Till is shown lying on his bed in 1954. /Getty

Emmett Till is shown lying on his bed in 1954. /Getty

The largest single lynching in American history took place on April 13, 1873 when a White mob that opposed the reconstruction of the South after the Civil War killed 150 Black people on Easter Sunday in Colfax, Louisiana.

Governments at all levels largely ignored or tolerated lynching, which became a form of entertainment for White communities. In one notorious case, Henry Smith, a Black man accused of murder, was burned alive in front of more than 10,000 people in Paris, Texas, in 1893. Many Whites took trains and even brought their children to watch.

The EJI founded the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, to shed light on racial violence and injustice. The memorial contains 805 steel monuments, each representing a county where a lynching occurred. Each victim's name is etched on a monument, but the number of anonymous victims must be even larger.

Lynching was a direct result of White supremacy, used to control and intimidate Black Americans. Although slavery was legally abolished after the Civil War, Whites in the South used lynching as a means of suppression and punishment.

Lynching Black men who were accused of raping or flirting with White women accounted for a quarter of lynching cases. Emmett Till lost his life over an alleged whistle, while the 1916 lynching of Jesse Washington in Waco, Texas was even more brutal, involving torture and mutilation. The White mob cut off his fingers, toes, and genitals in public, and then roasted him to death. His body parts were put on sale as "souvenirs." A White man made postcards to celebrate lynching and sent it to his father, jokingly calling the violent scene a " barbecue party" and claiming that it was more enjoyable than any sports event.

Being "disrespectful" to White people was enough to cost a Black person his or her life. In 1888, seven Black men in Alabama were killed for drinking water. In 1908, David Walker in Hickman, Kentucky, allegedly said some improper words to a White lady. His wife and four kids were killed. In 1918, Elton Mitchell, a Black man in Earl City, Arkansas, was hacked to death because he refused to work without pay.

Local, state, and federal governments in the U.S. have often ignored, tolerated, or even endorsed such racial violence. Anti-lynching legislation took more than a century to become law. It was not until 2022 that President Joe Biden signed a bill into law making lynching a federal hate crime. An offender will be sentenced to up to 30 years in jail.

U.S. President Joe Biden signs the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act in the Rose Garden of the White House in Washington, D.C., the United States, March 29, 2022. /Xinhua

U.S. President Joe Biden signs the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act in the Rose Garden of the White House in Washington, D.C., the United States, March 29, 2022. /Xinhua

What President Lyndon Johnson said many years ago could explain why the legislation was so slow – lynching brought benefits to the ruling class. "If you can convince the lowest White man he's better than the best colored man, he won't notice you're picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he'll empty his pockets for you," Johnson said.

Lynching is only one aspect of the suffering experienced by Black Americans. It exposes the evil of White supremacy and reflects the reality that racial discrimination is a deep-rooted malady of the U.S. that is difficult to eradicate.

Recently, Fox News host Jesse Watters questioned the need for passing the lynching law under Biden, arguing that there have been no lynchings for decades.

Lynching still happens to this day.

Eric Garner, a Black man, was choked to death in 2014. Ahmaud Arbery, an innocent Black man, was shot dead by Whites while jogging in 2020. These are two examples of modern-day lynchings.

Ida B. Wells, an American anti-lynching activist, once said the U.S. had no right to call itself "the land of the free." This painful reality persists for minorities in America today.

(The author, Professor Ji Hong, is a research fellow at the Institute of American Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com. Follow @thouse_opinions on Twitter to discover the latest commentaries in the CGTN Opinion Section.)