Editor's Note: The World Day to Combat Desertification and Drought falls on June 17 every year. This year's theme is "Her land. Her rights," emphasizing women's vital role in the global efforts to reduce and reverse land degradation. China has made unremitting efforts to combat desertification over the years. During the 2012-2022 period, China's accumulative afforestation area reached 64 million hectares, according to official data. In this article, we will tell you the story of a woman dedicating to building a botanical garden in the hinterland of Taklimakan Desert in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

Chang Qing collects seeds, September 2016.

Chang Qing collects seeds, September 2016.

Deep in the hinterland of China's largest desert, Taklimakan Desert, it might be unimaginable to see a botanical garden covered with lush, vibrant vegetation. This small yet precious oasis is the Tazhong botanical garden in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. It is also the second home of Chang Qing, the garden's designer and builder.

As a female senior engineer at the Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography (XIEG) under the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chang's life intertwined with the Taklimakan Desert over three decades ago.

In 1991, before the construction of a cross-desert highway, Chang and her colleagues were dispatched to Taklimakan Desert. Their task was to select vegetation for the shelterbelt along the road, a key step to protecting it from the raging sandstorms. The questions lingering in Chang's mind every day were how to design the road, how many sand dunes the road had to traverse and how many straw checkerboard barriers are needed to prevent sandstorms.

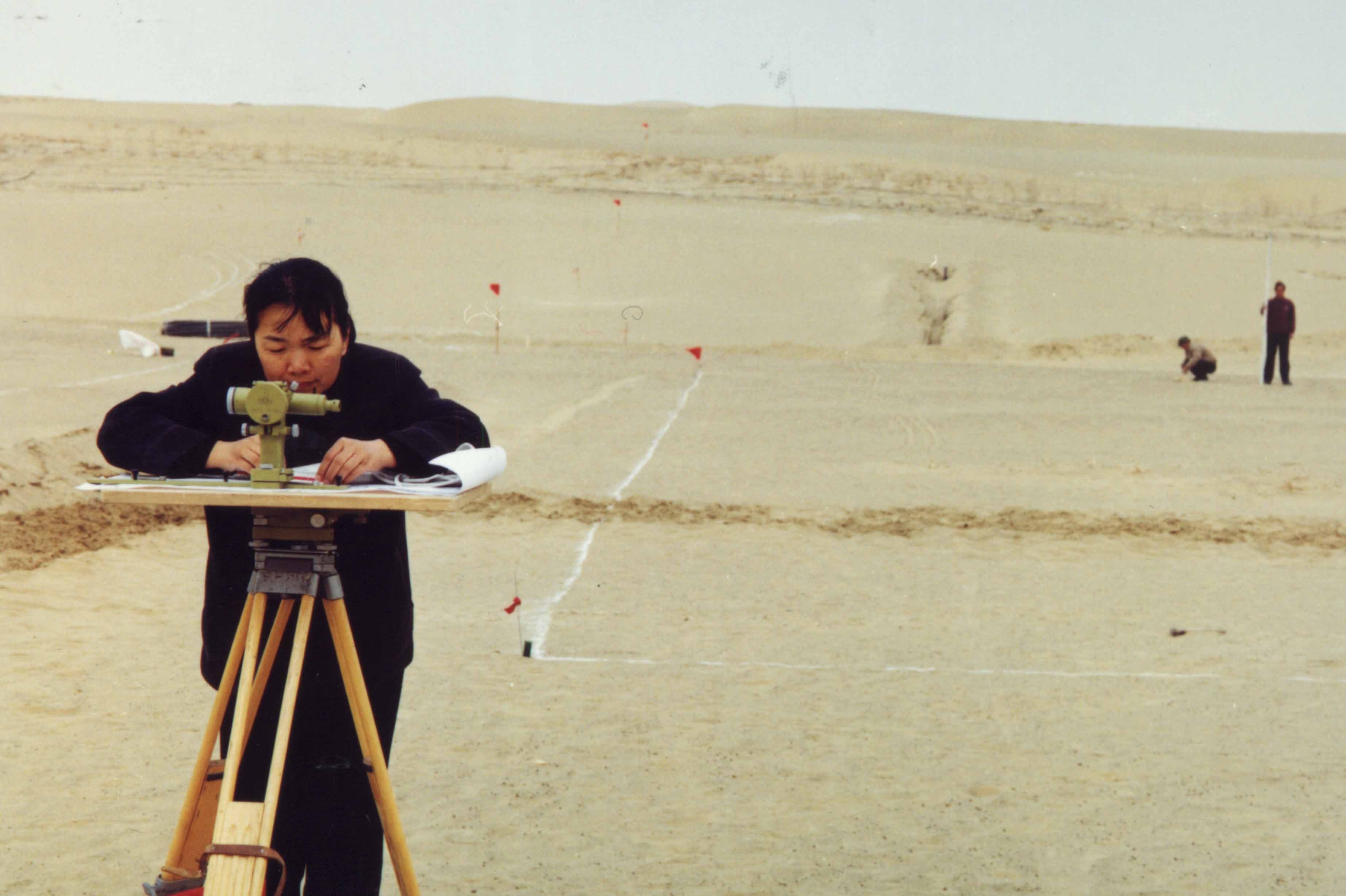

Surveying the site according to the drawings before construction of Tazhong botanical garden, 2002.

Surveying the site according to the drawings before construction of Tazhong botanical garden, 2002.

However, afforestation seemed nothing less than a mission impossible in this "sea of death." On top of its extreme weather and sandy saline-alkali soil, the desert has rich yet overly salty underground water resources, making it too harsh for most plants to survive in.

Chang said they had to set up their lab in a semi-subterranean pit encircled by walls made of mud and hay, and that the salty water was all they had to stay hydrated.

"If you get a bowl of water, half of it will be sand," recalled the dark-skinned scientist. Over the years, the merciless desert sun has burnt her skin while the sandstorms attacked her eyes, and she has to squint whenever she tries to see things clearly.

The situation took a favorable turn with the introduction and broad application of Israel's drip irrigation technology in 2000. In 2001, a "green barrier" that stretches 30.8 kilometers was successfully planted along the desert road, with a forest area of 191.3 hectares.

Three types of plants, namely tamarisk, sacsaoul and calligonum, played a major role in making the forest. They not only withstand the salty water, but also droughts. To race against time, Chang and her colleagues used cuttings instead of saplings to build the forest for the first time. Though it was hard to take care of, the result was surprisingly good.

Chang soon became accustomed to the harsh conditions in the desert, just like those desert plants.

In 2003, to nurture more viable vegetation varieties in the Taklimakan, a botanical garden was established and Chang was appointed its designer.

"If a severe disease or pests were to hit, it would be a fatal strike if the shelterbelt consisted of a single species," Chang explained. "However, if there are multiple kinds of vegetation, some of them still stand a chance to survive."

In search of the seeds of more plant species, Chang has left her footprints all across the deserts of Xinjiang.

"We often plant vegetation in spring and summer. In July and August, we would go into the wild to search for plants and record their locations. When autumn comes and their seeds mature, we would go back to collect the seeds and preserve these seeds before the winter comes," said Chang.

Growing saplings in the Tazhong botanical garden.

Growing saplings in the Tazhong botanical garden.

Their years of efforts have borne fruit. Growing out of nothing, the Tazhong botanical garden has become a green kingdom of over 20 hectares, where over 260 species of vegetation not only survive but thrive.

"Seeing the plant growing from a seed to a sapling then to a tree is very pleasing. It's like bringing up a child," said Chang. Even now, approaching 60 years of age, she spends 250 days of the year in the desert and is still working on a project to cultivate ornamental plants in the desert.

"Our knowledge of nature is so limited, not even a drop in the ocean," said Chang.

Apart from shelterbelt projects in other parts of China, Chang's research has also provided technical support in terms of desertification control for African and Central Asian countries.

"For me, blanketing the desert in green is a romantic cause worthy of lifelong devotion," Chang said.

(With input from Xinhua; all photos courtesy of Chang Qing)

(If you have specific expertise and want to contribute, or if you have a topic of interest that you'd like to share with us, please email us at nature@cgtn.com.)