World

18:10, 15-Mar-2018

Three takeaways from this year’s UN World Happiness Report

Xuyen N.

Can people find happiness by moving? The answer is both yes and no, according to the latest UN World Happiness Report released on Wednesday.

In addition to the usual rankings of happiest countries using a variety of social factors, the 2018 report examines the movement of people – both internally and across country lines – to assess the happiness consequences.

While Finland tops the list of happiest countries overall, it was also ranked number one in happiness for foreigners – migrants, refugees and those not born in the country.

Looking at the relationship between the attitudes of those who move for better lives, the people in the new countries that greet them and the families they leave behind, this year’s Happiness Report illuminates some of the interesting dynamics in the way happiness is supported by governments, institutions and the attitudes toward new people.

Below are three key takeaways from this year’s report:

1. Money isn’t everything

Happiness rankings are based on six key variables: GDP per capita, social support, healthy life expectancy, social freedom, generosity and absence of corruption. Thousands of people were asked to assess their happiness levels according to these factors in a Gallup World Poll between 2015 and 2017.

People enjoy a sunny day at the Esplanade in Helsinki, Finland, May 3, 2017. / VCG photo

People enjoy a sunny day at the Esplanade in Helsinki, Finland, May 3, 2017. / VCG photo

For each of the top 10 countries, the variable of social support contributes more than, or equal to, the country’s total happiness score. While material wealth and economic well-being is surely an indicator of happiness, the model also suggests that having strong relationships is just as important for understanding happiness.

When looking at immigrant communities, the study also suggests that the happiest places for foreign-born populations aren’t the richest countries, “but instead the countries with a more balanced set of social and institutional supports for better lives.”

2. Happiness can change, and does change

Looking at the responses from foreign-born residents compared to a country’s overall population, researchers wrote that one of the most striking findings of the report is that for the happiest countries, happiness was almost exactly the same for immigrants as it was for the rest of the population.

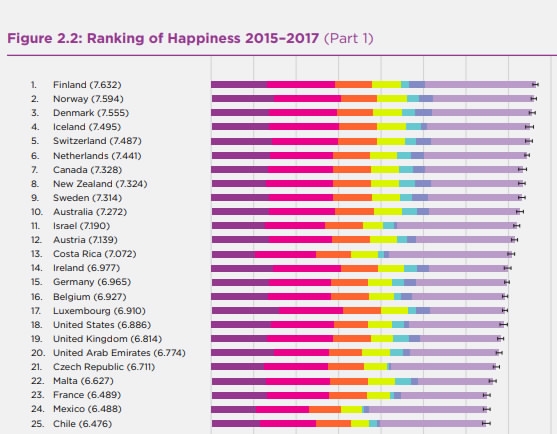

The top 25 countries for overall happiness, with Finland topping the list / source: UN World Happiness Report

The top 25 countries for overall happiness, with Finland topping the list / source: UN World Happiness Report

The fact that these the two rankings almost mirror each other in places like Finland, Norway and Denmark show that “immigrant happiness depends predominantly on the quality of life where they now live,” suggesting that “happiness can change, and does change, according to the quality of the society in which people live.”

3. Happiness of rural-urban migrants needs more attention

One of the largest movements of people is not immigrants or refugees, but the exodus of people from the countryside to the city. This phenomenon is especially prevalent in the developing world, with China’s recent experience being called the greatest mass migration in history. Between 1990 and 2015, China by itself accounted for 30 percent of the increase in the developing world’s urban population.

So do the happiness levels of people who move from the country to the city match the happiness levels of immigrants to new countries? Initial scores indicate that the answer is “No.”

Tens of thousands of migrants in Beijing joined the world's largest annual human migration to head back home on February 13, 2017, one day before the Lunar New Year Eve. / VCG photo

Tens of thousands of migrants in Beijing joined the world's largest annual human migration to head back home on February 13, 2017, one day before the Lunar New Year Eve. / VCG photo

Using a different methodology than the overall happiness rankings, the study for studying rural-urban migrants in China comes from a survey conducted by the country's National Bureau of Statistics in 2003, with most of the information reflecting attitudes in 2002. Respondents were asked to rate their well-being on a scale of “not happy at all” to “very happy,” with “don’t know” as an option.

The initial findings showed that despite having higher average incomes, migrants had a lower average happiness score. Exploring possible causes, including false expectations about urban conditions or that migrants are willing to sacrifice current happiness for future happiness, the authors found nothing conclusive about the initial findings, urging the global community to conduct more extensive research.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3