Opinions

18:35, 15-Mar-2018

What is the ultimate test of a political system?

Zhang Weiwei

Editor's Note: Zhang Weiwei is a Chinese professor of international relations at Fudan University, and a senior research fellow at the Chunqiu Institute. He is the author of The China Wave: Rise of a Civilizational State. The Chinese Way by Zhang Weiwei is a 10-part CGTN Digital series casting a critical eye over the governance of modern China. Professor Zhang identifies merits and flaws in the Chinese system and contrasts the China model with Western equivalents in a series of short films.

- A unique system of political governance has underpinned China’s rise.

- China’s system has allowed it to focus on the long-term, rather than the next election.

China’s development over the past 40 years is closely linked to its philosophy of good political governance. Scholar Zhang Weiwei asserts that China’s rise may lead to a paradigm shift from ‘democracy versus autocracy’ to ‘good governance versus bad governance.’

China's dramatic rise in the past four decades is indeed remarkable, even for those who lived through it. Some international comparisons make this point clearer.

- Compared to other developing countries, China has performed better than all combined in terms of poverty eradication. Almost 80 percent of the world’s poverty eradication has taken place in China since the 1980s.

- Compared to other transitional economies, China has also performed better than all combined. For example, China’s foreign exchange reserves alone are larger than the combined GDPs of Eastern Europe and Russia. This is significant given the fact that Russia’s economy was larger than China’s at the time of the Soviet breakup.

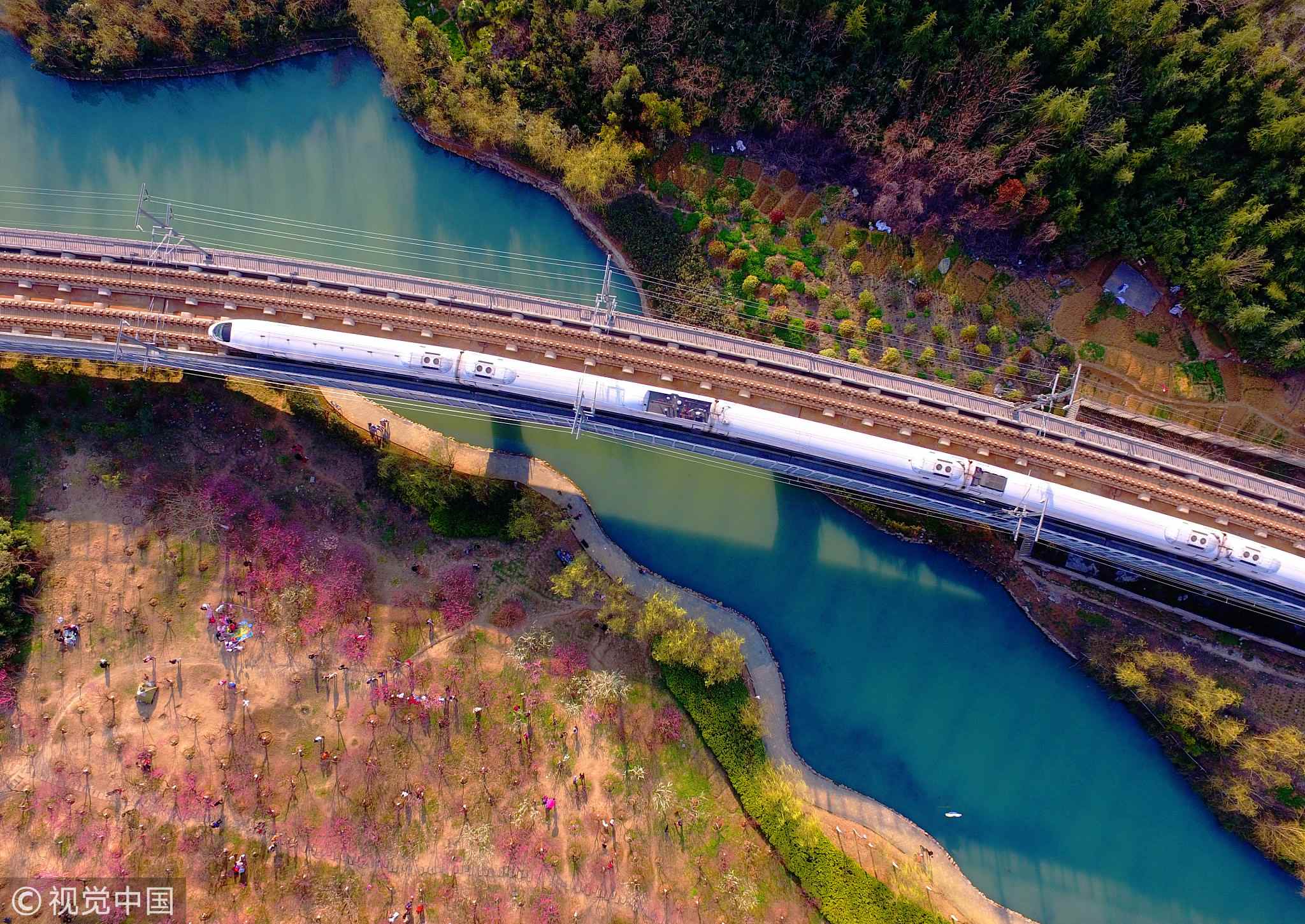

- Compared to the West, China has also performed better than many Western countries in many respects. Take China’s developed regions, which have a combined population of over 300 million people – about the same as the total population in the US. Cities like Shanghai already surpass cities like New York in “hardware,” such as airports, subways, high speed trains, shopping facilities and city skylines. And in terms of “software” such as life expectancy, child mortality rate, home ownership and street safety, developed regions in China come out ahead.

A highspeed train passes through Kuanghe Park in Hefei, Anhui Province, China, March 12, 2018. /VCG Photo

A highspeed train passes through Kuanghe Park in Hefei, Anhui Province, China, March 12, 2018. /VCG Photo

China has its share of problems, some of which are serious and require earnest solutions, but its overall success is beyond doubt.

What’s the explanation for this success? Some claim it is due to foreign direct investment (FDI), but Eastern Europe has received far more FDI in per capita terms; Some claim it’s due to China’s cheap labor, but India and Africa offer much cheaper labor; Some claim it’s due to an authoritarian government, but there are authoritarian governments, as defined by the West, everywhere in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Arab world, but none have accomplished what China has achieved.

China’s rise has to do with the Chinese philosophy for political governance.

- Zhang Weiwei

If none of these explanations can explain China’s success, one should be encouraged to think outside the box. China’s rise has to do with the Chinese philosophy for political governance, which is a vast topic. But I will focus on some of its key concepts.

There are two distinctive concepts in China’s political governance; minyi and minxin. Minyi refers to "public opinion," and minxin to "the hearts and minds of the people" (this is only an approximate English translation).

The two concepts were first put forth by Mencius, the great Confucian master, during the 4th century B.C. According to Mencius, minyi or public opinion, can be fleeting and change overnight (especially in today’s Internet age), while minxin or "hearts and minds of the people," tends to be stable and lasting, reflecting the whole and long-term interest of a nation.

Over the past four decades, the Chinese state has generally practiced "rule by minxin." This allows China to plan for the medium to long-term and even for the next generation, rather than for the next election, as the case with many Western democracies.

China plans for the medium- to long-term and even for the next generation, rather than for the next election.

- Zhang Weiwei

Furthermore, the two concepts have led to the focus on the importance of competent leadership and the practice of meritocracy (xuanxian renneng, or selecting and appointing the virtuous and competent). I disagree with Dr Francis Fukuyama on his end-of-history thesis, but he is right in observing in his book “The Origins of Political Order” that “it is safe to say that China invented modern bureaucracy, that is, a permanent administrative cadre selected on the basis of ability rather than kinship or patrimonial connection.”

Francis Fukuyama speaks during a lecture at Fudan University, Shanghai, China, December 2010. /VCG Photo.

Francis Fukuyama speaks during a lecture at Fudan University, Shanghai, China, December 2010. /VCG Photo.

The Communist Party of China has adapted this tradition to China’s new reality and built an impressive system of selecting its leaders based on merit and performance. If you look at Xi Jinping’s profile, he has served as a top leader for the provinces of Fujian and Zhejiang as well as the municipality of Shanghai – a region consisting of over 120 million people and an economy close to the size of India, before he became a member of the Politburo Standing Committee. He was then given another five years to get familiar with state affairs at the national level before he was elected China’s top leader. China’s system of meritocracy is apparently more effective than the American model of relying simply on elections in producing competent and trust-worthy leaders.

Good governance versus bad governance is a much better political paradigm than democracy versus autocracy.

- Zhang Weiwei

Good governance versus bad governance is a much better political paradigm than that of democracy versus autocracy, which is an outdated ideological legacy from the Cold War. China’s success shows that whatever the political system, it must all boil down to good governance.

In other words, the ultimate test of a good political system is to what extent it can ensure good governance in the eyes of the people. The dichotomy of democracy versus autocracy sounds increasingly hollow in today’s complex world, given the large number of poorly governed “democracies.”

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3