China

17:49, 22-Nov-2017

Survey backs China carbon trading to help cap emissions

Nick Yates

With the eyes of environmentalists worldwide on the carbon trading scheme that China is expected to launch soon, a new survey has shown cautious optimism about its prospects for lowering emissions and combatting climate change.

The 2017 China Carbon Pricing Survey, led by independent research organization the China Carbon Forum (CCF), asked China-based enterprises and carbon-emitting enterprises for their views on how efficient the scheme will be.

Carbon trading schemes, also known as emissions trading schemes (ETS), are a significant plank of global efforts to lower emissions. Already in place in big markets like the EU and the US, they put a cap on the overall amount of emissions from industries. In order to keep within the agreed emission limit, the government issues permits. In case a company breaches its carbon emission limit, then it has to buy more permits. If the company emits less than the set limit, the ETS allows them to sell the excess permits, thereby incentivizing them to be more green.

China has been working on a national carbon trading scheme for years, with President Xi Jinping setting a target for it to be launched before the end of 2017. In the run-up, the country has been operating pilot versions of the scheme in seven cities.

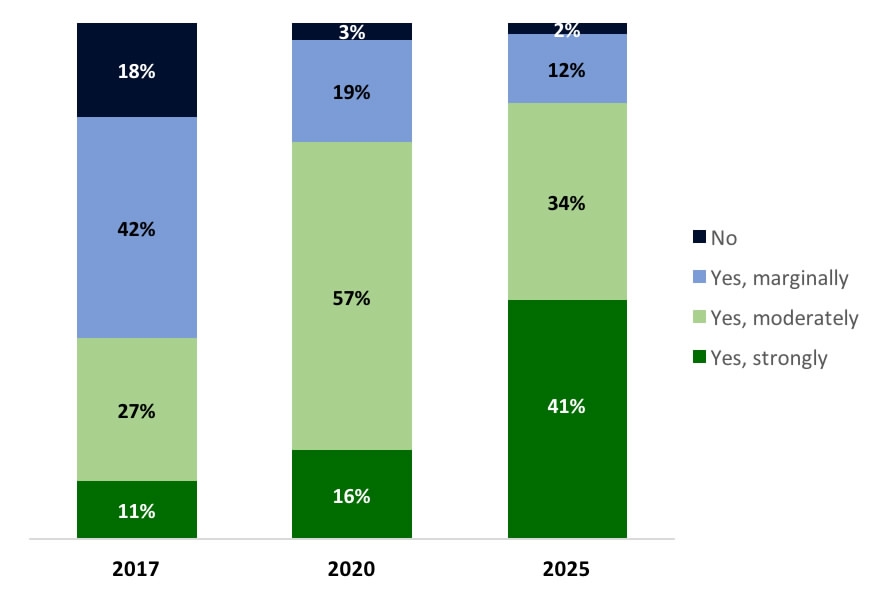

The survey asked, “Do you expect the ETS in China to affect investment decisions in 2017? 2020? 2025?” /CCF Photo

The survey asked, “Do you expect the ETS in China to affect investment decisions in 2017? 2020? 2025?” /CCF Photo

Nearly half the survey respondents (47 percent) said they expect the ETS to be fully functional by 2020 or earlier. Almost as many (44 percent) said it will be sometime between 2021 and 2025 before China has a fully functional carbon market backed up by legislation and monitoring of companies’ emissions.

Survey respondents expect carbon trading to affect companies' investment decisions increasingly. In 2017, 38 percent expect investment decisions to be strongly or moderately affected, and by 2025, this figure rises to 75 percent.

For companies to be motivated, emissions permits need to be valuable assets. Those polled said they thought prices in the national ETS would steadily rise, from about 38 yuan (5.74 US dollars US dollars) per tonne of CO2 emitted in 2017 to 74 yuan per tonne in 2020 and 108 yuan per tonne in 2025.

However, the report authors tempered this, stressing how their research showed the price levels remain highly uncertain, especially in the more distant future. It has been a frequent problem in carbon trading schemes elsewhere in the world for authorities to supply too many permits and prices to be low.

China Carbon Pricing Surveys conducted by the CCF in 2013 and 2015 found people optimistic about price rises in the Chinese pilot schemes, but they failed to match expectations, actually decreasing from 2014 to 2016.

Citing EU difficulties in this regard, Dutch Ambassador to China Ed Kronenburg said at the survey report launch on Wednesday, “The first question to be answered is at what level to set the cap, and how do you monitor emissions to make sure it really an effective mechanism.”

As to when the scheme will enter operation, CCF Vice Chairman Dimitri de Boer cited concern that it would be premature to launch it in 2017. “But it doesn’t really make that much difference,” he said. “In terms of whether it means anything on the ground, it doesn’t matter that much if it starts this year, next year or even in 2019. What matters more is when it is fully functional.”

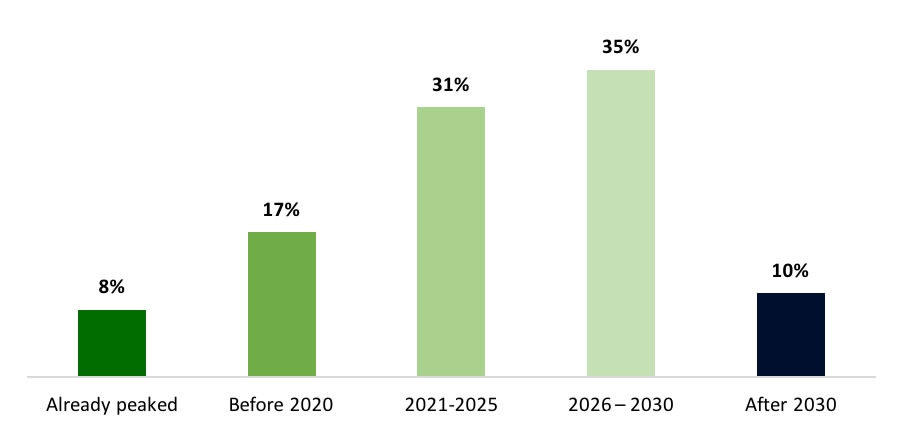

The survey asked, “When do you expect China’s emissions will peak?” /CCF Photo

The survey asked, “When do you expect China’s emissions will peak?” /CCF Photo

Chinese leaders have set a target of the country’s emissions peaking by 2030. Ninety percent of respondents said they expect that target will be met, while 55 percent said it would be achieved by 2025.

De Boer said he took some of the report’s more positive conclusions like this one “with a pinch of salt” because of how few actual enterprises were interviewed. Only a quarter of the 260 responses came from those most directly affected by the ETS.

“The industry response rate was lower than expected,” said the report. It attributed this to the fact that “some industry representatives may not yet consider themselves to be in a position to provide expectations”, and there was acknowledgment at the report launch that the results were probably distorted by industry respondents likely having been those who are best prepared for the ETS introduction.

“There’s a body of opinion that the first few years will be seen as kind of a first phase of experimenting,” said CCF Research Manager Huw Slater. “After 2020 will be a much more serious implantation of ETS, and so by the mid-2020s we will see a more significant positive impact, and a higher price of carbon.”

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3