climate

19:02, 13-Dec-2017

Arctic report card: Permafrost thawing at a faster pace

Permafrost in the Arctic is thawing at a faster clip, according to a new report released Tuesday.

Water is also warming and sea ice is melting at the fastest pace in 1,500 years at the top of the world.

The annual report released Tuesday by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) showed slightly less warming in many measurements than a record hot 2016. But scientists remain concerned because the far northern region is warming twice as fast as the rest of the globe and has reached a level of warming that’s unprecedented in modern times.

“2017 continued to show us we are on this deepening trend where the Arctic is a very different place than it was even a decade ago,” said Jeremy Mathis, head of NOAA’s Arctic research program and co-author of the 93-page report.

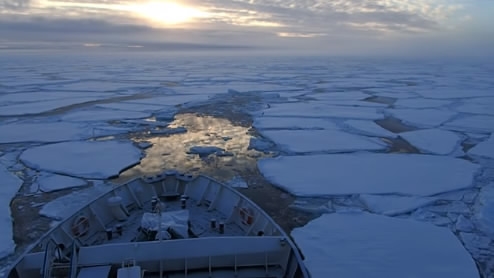

An iceberg melts in Kulusuk, Greenland near the arctic circle, Aug, 16, 2005. /AP Photo

An iceberg melts in Kulusuk, Greenland near the arctic circle, Aug, 16, 2005. /AP Photo

Findings were discussed at the American Geophysical Union meeting in New Orleans.

“What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic; it affects the rest of the planet,” said acting NOAA chief Timothy Gallaudet. “The Arctic has huge influence on the world at large.”

Permafrost is the permanently frozen layer below the Earth’s surface in frigid areas. Records show the frozen ground that many buildings, roads and pipelines are built on reached record warm temperatures last year nearing and sometimes exceeding the thawing point. That could make them vulnerable when the ground melts and shifts, the report said. Unlike other readings, permafrost data tend to lag a year.

Preliminary reports from the US and Canada in 2017 showed permafrost temperatures are “again the warmest for all sites” measured in North America, said study co-author Vladimir Romanovsky, a professor at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks.

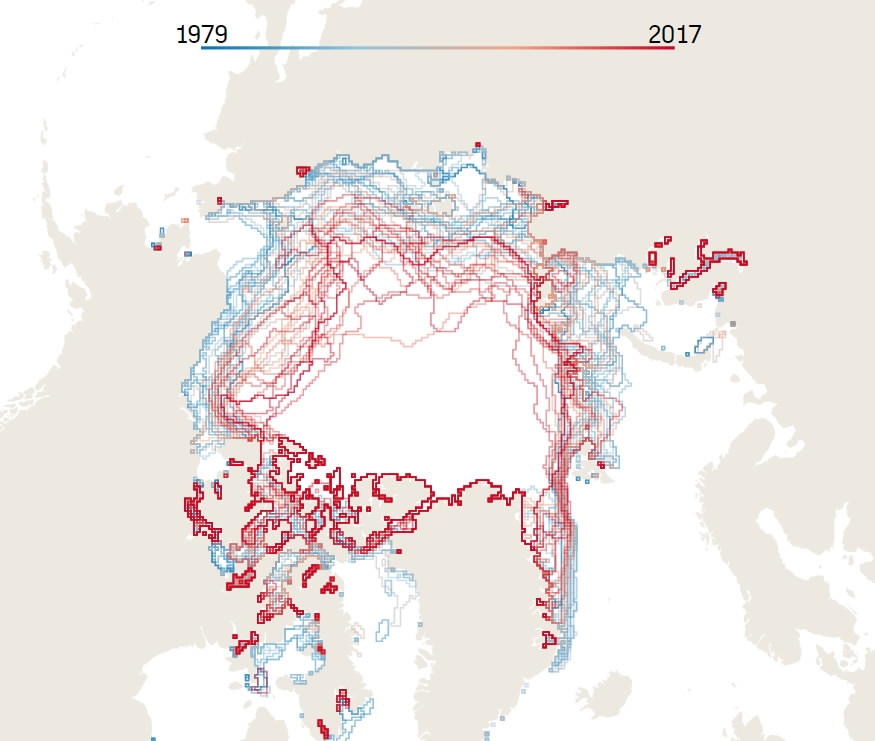

September sea ice continues to decline /US National Snow and Ice Data Center Photo

September sea ice continues to decline /US National Snow and Ice Data Center Photo

Arctic sea ice usually shrinks in September and this year it was only the eighth lowest on record for the melting season. But scientists said they were most concerned about what happens in the winter -- especially March -- when sea ice is supposed to be building to its highest levels.

Arctic winter sea ice maximum levels in 2017 were the smallest they’ve ever been for the season when ice normally grows. It was the third straight year of record low winter sea ice recovery. Records go back to 1979.

About 79% of the Arctic sea ice is thin and only a year old. In 1985, 45% of the sea ice in the Arctic was thick, older ice, said NOAA Arctic scientist Emily Osborne.

New research looking into the Arctic’s past using ice cores, fossils, corals and shells as stand-ins for temperature measurements show that Arctic ocean temperatures are rising and sea ice levels are falling at rates not seen in the 1,500 years. And those dramatic changes coincide with the large increase in carbon dioxide levels in the air from the burning of oil, gas and coal, the report said.

The sea ice cover continues to be relatively young and thin with older, thicker ice comprising only 21 percent of the ice cover in 2017 compared to 45 percent in 1985. /NOAA Photo

The sea ice cover continues to be relatively young and thin with older, thicker ice comprising only 21 percent of the ice cover in 2017 compared to 45 percent in 1985. /NOAA Photo

This isn’t just a concern for the few people who live north of the Arctic Circle. Changes in the Arctic can alter fish supply. And more ice-free Arctic summers can lead to countries competing to exploit new areas for resources. Research also shows changes in Arctic sea ice and temperature can alter the jet stream, which is a major factor in US weather.

This is probably partly responsible for the current unusual weather in the United States that brought destructive wildfires to California and a sharp cold snap to the South and East, according to NOAA scientist James Overland and private meteorologist expert Judah Cohen.

“The Arctic has traditionally been the refrigerator to the planet, but the door of the refrigerator has been left open,” Mathis said.

Outside scientists praised the report card.

“Overall, the new data fit with the long-term trends, showing the clear evidence of warming causing major changes,” in the Arctic, said Pennsylvania State University ice scientist Richard Alley.

6196km

Source(s): AP

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3