Politics

17:01, 15-Nov-2017

US takes carrot and stick approach toward Myanmar as Tillerson meets Suu Kyi

By Wang Lei

The United States will provide additional 47 million US dollars in aid for Rohingya refugees, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said in Myanmar on Wednesday, stressing that broad-based sanctions against the country are "not advisable at this time."

"We want to see Myanmar succeed... I have a hard time seeing how that (sanctions) helps resolve this crisis," he added.

However, the top US diplomat also called for a credible and impartial investigation into allegations of human rights abuses against Rohingya Muslims and said targeted sanctions on individuals in Myanmar "may be appropriate."

Amid the cooling of relations between Myanmar and the West following the latter's criticism against the Southeast Asian country over its handling of the Rohingya crisis, Tillerson's visit has highlighted Washington's carrot and stick approach toward Myanmar.

More than 600,000 Rohingya Muslims have fled to Bangladesh since late August, driven out by a Myanmar military counter-insurgency clearance operation in Rakhine State that a top UN official has described as a textbook case of "ethnic cleansing."

Suu Kyi denies being 'silent'

"We're deeply concerned by credible reports of wide-spread atrocities committed by Myanmar's security forces and by vigilantes who were unrestrained by the security forces during the recent violence in Rakhine State," Tillerson told a joint news conference with Aung San Suu Kyi, the leader of a civilian administration that is less than two years old and shares power with the military.

Myanmar's State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi talks to media during a press conference after she met with US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson at Naypyitaw, Myanmar, November 15, 2017. /Reuters Photo

Myanmar's State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi talks to media during a press conference after she met with US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson at Naypyitaw, Myanmar, November 15, 2017. /Reuters Photo

Suu Kyi, criticized by Western media for her "silence" over the violence, said she has not been silent and stressed that she has tried not to set ethnic communities against each other.

The mostly Muslim Rohingya, estimated at about 1.1 million people before the latest exodus, are denied citizenship and viewed as illegal immigrants in Buddhist-majority Myanmar.

A Rohingya refugee man pours water from a well installed near toilets in Palong Khali refugee camp in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, November 15, 2017. /Reuters Photo

A Rohingya refugee man pours water from a well installed near toilets in Palong Khali refugee camp in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, November 15, 2017. /Reuters Photo

Tillerson also held talks with the commander of Myanmar's armed forces, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing during his one-day stop in Naypyidaw.

"It is incumbent upon the military and security forces to respect these commitments of the civilian government; to assist the government in implementing them and to ensure the safety and security of all people in Rakhine State," Tillerson said.

On Tuesday, Tillerson and Suu Kyi met during the 12th East Asia Summit in the Philippines, where Myanmar's state counselor sought to explain her government's efforts to resolve the crisis and its plans for the eventual voluntary repatriation of the Rohingya.

The West's love-hate relations with Suu Kyi

The treatment of the Rohingya has emerged as the biggest political challenge for Suu Kyi since she came to power in 2015. Once hailed an icon of human rights and the hope of democracy in Myanmar, she is now facing harsh criticism and even calls for the Nobel committee to revoke her peace prize.

Born in 1945, Suu Kyi is the daughter of Myanmar's independence hero, General Aung San. He was assassinated in July 1947 when Suu Kyi was only two.

Suu Kyi received education at Oxford University in Britain and lived in India, Japan and Bhutan, before settling in the UK. She married British academic Michael Aris and has two children.

She returned to Myanmar in 1988 to take care her critically ill mother at a time of political upheaval in the country. "I could not as my father's daughter remain indifferent to all that was going on," she said in a speech in Yangon (Rangoon) on August 26, 1988, kicking off her epic political career.

Suu Kyi spent 15 of 21 years from 1989 to 2010 under house arrest or in prison, barred from politics by the ruling junta. In 1991, she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for being "an outstanding example of the power of the powerless."

Suu Kyi was finally released on November 13, 2010, partly a result of Western pressure on the military government. Four years later, she led her National League for Democracy to a majority win in Myanmar's general election. Since the constitution forbids her from becoming president for her children's foreign passports, Suu Kyi got the official title of state counselor.

The West eased sanctions on Myanmar after Suu Kyi became the de facto leader. Nevertheless, she did not become a close ally of the West as previously expected but adopted a pragmatic and balanced diplomatic approach instead, Chinese experts said, calling it a shock to the West.

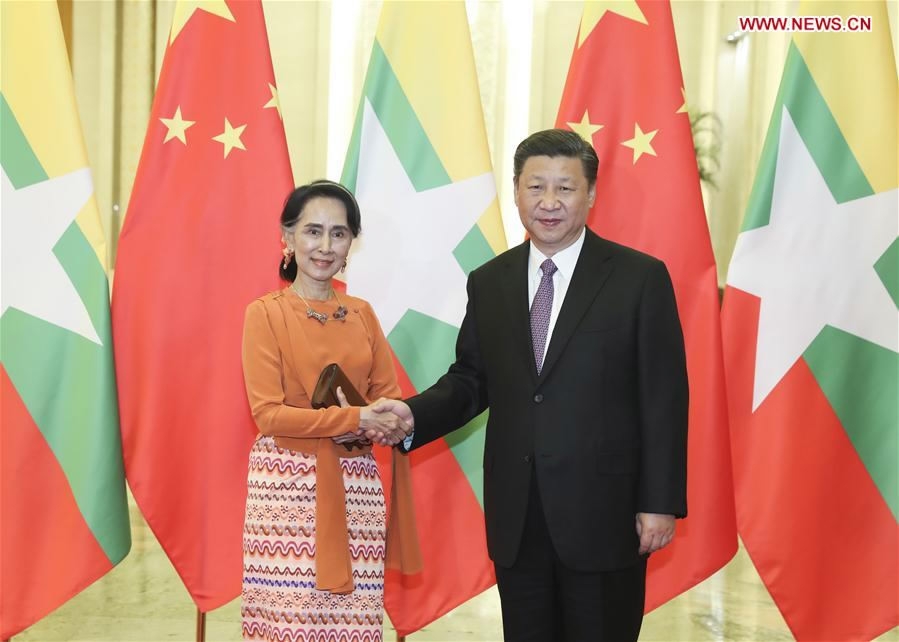

Song Qingrun, a researcher at China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, told Chinese media that Suu Kyi is by and large a pragmatic politician, noting that she visited ASEAN countries first and then China, before going to the US.

Chinese President Xi Jinping (R) meets with Myanmar's State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi after the two-day Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing, May 16, 2017. /Xinhua Photo

Chinese President Xi Jinping (R) meets with Myanmar's State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi after the two-day Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing, May 16, 2017. /Xinhua Photo

Western media's fierce criticism of Suu Kyi reflected dissatisfaction toward her foreign policies, said Zhu Zhenming, a researcher at China's Yunnan Academy of Southeast Asian and South Asian Studies.

Ren Nanling, a scholar on Southeast Asian studies, holds a similar view. He noted that Suu Kyi's refusal to adopt completely pro-Western policies has led to frustrations in the West.

To rally maximum support for Myanmar from the international community, the government led by Suu Kyi strives to enhance ties extensively with neighboring countries and develops relations with major powers in a flexible and pragmatic way, Ren said.

2977km

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3