Tech & Sci

11:45, 11-Aug-2017

US researchers develop affordable lead sensor for home and city water

By Fan Yixin

Researchers at University of Michigan (UM) have developed a cheap lead sensor for home and city water quality inspection, and are seeking partnership to bring a new lead sensor to production.

The sensor designed, potentially costing around 20 US dollars, could alert residents and authorities to the presence of the lead within nine days, the University said in a press release on Thursday.

The old water system in Flint, Michigan, was stable for decades until the 2014 Flint water crisis when over 100,000 residents were suddenly exposed to high levels of neurotoxin due to corroded lead piping caused by water quality change.

According to the researchers, standard water sample tests normally miss any lead that leaches into the water from home's own pipes by requiring users to run water for several minutes. The traditional sensors also tend to be on the pricey side.

Mark Burns, Professor of Chemical Engineering at UM, and his colleagues decided to develop an inexpensive sensor to solve the problem. They hope the new sensor could be placed at key points in city water systems and residents’ homes.

The trick, according to the researchers, is separating lead from other metals that might be present in water, most of them only “hazardous in very high doses.”

Wen-chi Lin, a Taiwanese chemistry engineering PhD graduate on Burn’s team, had the solution. Lin designed a sensor that differentiates between lead and other metals like iron.

"Since iron is the most common metal in water and is basically harmless (besides having a bad odor), we see it as interfering with our sensor," said Lin.

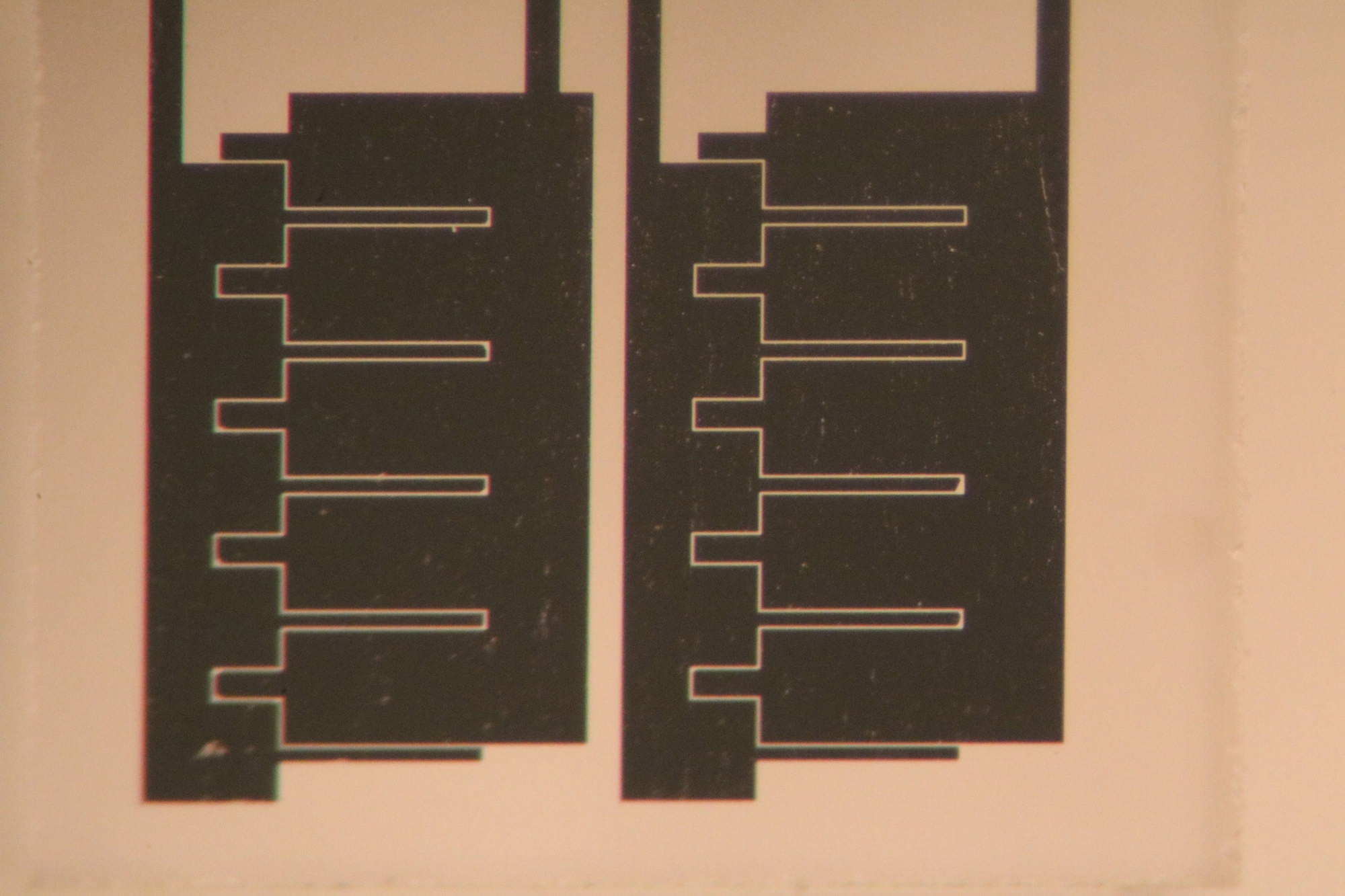

Lin’s design relies on two pairs of electrodes. The positive electrode and its neutral neighbor set up an electron-poor environment, while the negative electrode and its neutral neighbor create an electron-rich environment.

A close-up view of the lead sensor, featuring two pairs of electrodes. It could enable cities and homeowners to pinpoint pipes that taint water with lead. /University of Michigan

A close-up view of the lead sensor, featuring two pairs of electrodes. It could enable cities and homeowners to pinpoint pipes that taint water with lead. /University of Michigan

“The negative electrode offers electrons to positive ions, capturing most metals. The metals are already oxidized in water, meaning they've given up some of their electrons, so they prefer an opportunity to get electrons back,” noted in the press release. "However, lead is attracted to the positive side of the electrode set – it is the only contaminant metal that readily loses more electrons and oxidizes further."

The research team hopes for better performance in the future.

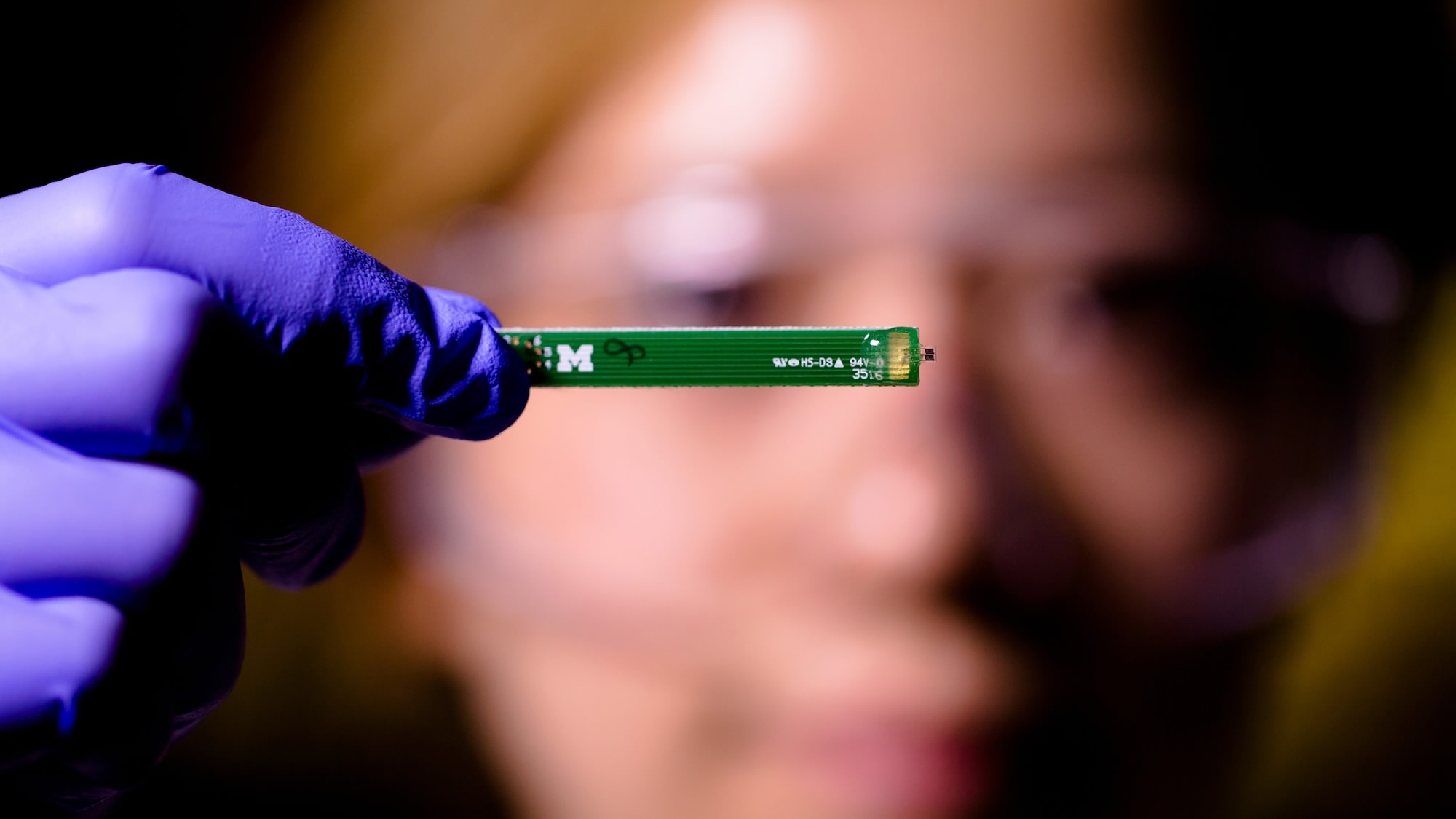

(Top photo: Wen-chi Lin shows off her electronic lead sensor design. It could enable cities and homeowners to pinpoint pipes that taint water with lead. /University of Michigan)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3