Opinions

22:54, 25-Jan-2018

Opinion: What can China offer for inclusive global growth?

Guest commentary by Fu Jun

We live in fast-moving times and in an increasingly interconnected world. Globalization has reached new highs in the 21st century. Together with new technology, it has brought benefits to many, but the gains have not been distributed evenly within or across countries – a source of discontent of late. Indeed, when about half of the world’s wealth goes to the top 5 percent of the population, and almost one-fifth to the highest 1 percent, the economy is in trouble, for the simplest of economic principles tells us that equilibrium must exist between supply and demand for growth to continue.

Pressing global issues call for global efforts. What can China offer for inclusive global growth? Without attempting to be comprehensive, let me try to answer this question by highlighting some of China’s new initiatives along the themes of ideas, institutions, and infrastructures.

New educational initiative

VCG Photo

VCG Photo

Let me begin with education – a lesson China has learnt and benefited from, and is now ready to give back. As one may recall, when China started its reforms and opening-up process in the late 1970s, Mr Deng Xiaoping – China’s then paramount leader – decided to send large numbers of Chinese students to study abroad. Now it is increasingly recognized that, in a way more profound than physical capital, growth is fostered by development of human talent, and that where sizable investment has been made in education and other elements of the human factor, advancing technology – a byproduct of sophisticated human ideas – has played a key role in economic growth or industrial catch-up.

In the light of this, China established the Institute of South-South Cooperation and Development at Peking University (ISCD) in April 2016, with the first 50 students from developing countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America enrolling in September that year. ISCD aims to share developmental knowledge and experience with other developing countries, offering graduate programs for master’s and doctoral degrees in national development. It symbolizes a systematic shift in China’s technology transfer to the developing world from hardware to software, i.e., knowledge and ideas.

This milestone event was to substantiate the new educational initiative on South-South cooperation and development announced by Chinese President Xi Jinping during the 70th anniversary celebrations of the UN in New York in September 2015. It represents China’s commitment to equitable, inclusive and sustainable development with a global perspective. “As long as we keep to the goal of building a community of shared future for mankind and work together to fulfill our responsibilities and overcome difficulties, we will be able to create a better world and enabling better lives for our peoples,” Mr Xi reaffirmed at Davos in January 2017.

The idea of building a “community of shared future for mankind” seeks to enhance multilateralism to address global and regional imbalances. Development on a wider scope, it is believed, could generate new impetus for inclusive global growth. According to the World Map of Economic Growth by Harvard Center International Development (CID), countries with the biggest potential for growth in the coming decade are mostly located in South Asia and East Africa, whilst some in the Middle East and South America are also poised to take off. Meanwhile, growth will slow down in advanced economies. The US is anticipated to grow at 2.58 percent per annum; UK at a slightly higher 3.22 percent; Germany, one of the leading economies in Europe, at only 0.35 percent.

Now, the Chinese economy, on the other hand, is the second largest in world and still grows at a rate roughly 3 times that of the US, contributing to more than 1/3 of the global growth in 2017, and its imports grew by over 18 percent last year, making it a powerful engine of the world economy. It is very conceivable that, as China increasingly moves to the center of the world, it can play a positive role connecting the developed and developing countries closer together in all sorts of win-win scenarios. But to bring good visions to fruition, it takes leadership not only in ideas and but also in actions, as well as empathy that glues humanity together.

Let’s improve infrastructure

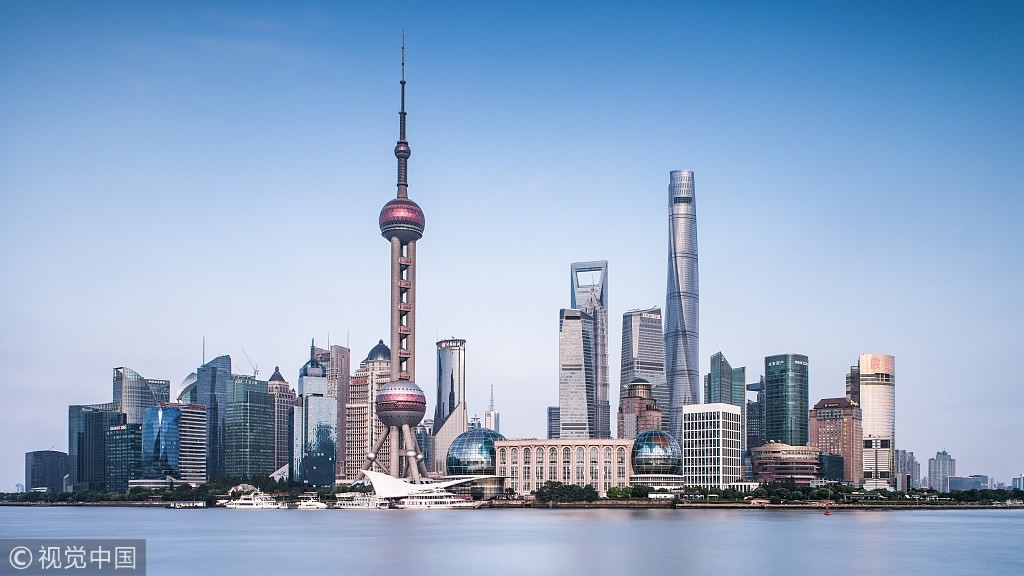

VCG Photo

VCG Photo

One manifestation of this kind of endeavor on the ground is China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Launched in 2013, BRI aims to forge partnerships – or joint ventures if you will – along the traditional silk roads to improve inter-connectivity across Asia and beyond with infrastructure projects such as roads, bridges, ports, gas pipelines, power grids, and fiber-optic cables. Indeed, to facilitate inclusive growth, it is critical to deploy not only means of production but also means of delivery and access to information. Here, what one may envision – especially from the perspective of low-income countries – is a mirror image of China’s own growth story, epitomized in the buzzword: “Want to get rich, build roads first!”

Earthy as that sounds, it is not without theoretical and empirical grounds. That is, the state has a critical role to play in providing public goods, especially long-run risky physical infrastructure. Indeed, in the past 3 years, for example, the Chinese government invested more than 182 billion US dollars to expand and improve the internet fiber optic network, and between 1996 and 2016, China built 2.6 million miles of roads – including 70,000 miles of highways – connecting 95 percent of all the villages of the country. Here, the private sector didn’t seem to have worked well by itself; private businesses were more likely to pop up along the way. Lest one forget, even in Shenzhen – China’s foremost market-driven special economic zone – initial rounds of infrastructure were built by army engineers. Private investments, domestic or foreign, followed later.

Let’s augment institutions

VCG Photo

VCG Photo

In this context, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) – a China-led multilateral development bank (MDB) – has its rationale. Proposed by China in 2013 and launched in 2015, the idea is to bring states or mostly sovereign money together in partnerships to address the daunting infrastructure shortfalls across Asia and beyond. According to the Asian Development Bank (ABD), Asia alone needs to invest 1.7 trillion dollars annually in infrastructure until 2030 to maintain climate-resilient growth momentum. Serving as an augmentation to – but not a substitution of – the existing international financial institutions, the AIIB currently has an approved membership of 84 (and still growing) from all continents, making it one of the largest MDBs in the world.

Note that all AIIB members are signatories to the Paris Agreement and the bank has an energy strategy with priorities on renewable energy and projects that enhance energy efficiency. Pledging to be “lean, clean and green” and with its projects also open to private investments, the AIIB has great potential for scaling up financing for inclusive and sustainable development in the fastest growing regions of the world. Incidentally, as another example of institutional building and commitment to green development which has global implications, China rolled out a nationwide carbon trading scheme starting in the power generation sector before the end of 2017. It is by far the largest carbon-trading market in the world.

Let’s share experience and lessons

VCG Photo

VCG Photo

2018 marks the 4oth anniversary of China’s reforms and opening-up. In the past 40 years, Chinese economic growth has been phenomenal. China has lifted more than 700 million people out of poverty, and pledged to eradicate all poverty by 2020. For 1.3 billion Chinese – roughly 1/5 of the world’s population –- average life expectancy has risen from 67.9 in 1981 to 76.5 in 2016. China’s GDP per capita was about 150 dollars in 1978. Today’s figure is close to 9,000 dollars, and is projected to reach 12,700 dollars – the threshold of a high-income country – around 2025. China overtook Japan as the world’s second largest economy in 2009, and became the world’s largest trading nation in 2013. China’s rapid rise from an agrarian backwater to a global economic power has lessons for other developing countries, if only because of similar stages of development. And this brings us back to the issue of education.

Indeed, many Chinese universities have been teaching international students. So what’s special about ISCD? The program’s focus is on national development for the developing world, and as such it is meant for inclusive global growth. At the core of its curricula is a nexus of regular courses designed for students to learn systematically in terms of both intellectual rigor and managerial skills. Taught in English by a faculty who have all received education both from home and abroad, the core covers topics such as leadership, public management, public policy in micro- and macro-economic perspectives, statistical analysis, good governance, and Chinese approaches to reforms and opening-up. Fanning out from the core are four cross-cutting policy domains as practiced in China – growth and poverty alleviation, population and health, climate change and environmental protection, education and innovation – which can be scaled up to the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

To further contextualize the learning process, field trips are organized along the trajectories of China’s reforms and opening-up – from rural areas, to special economic zones, to coastal cities, to the interior parts – such that students get to appreciate the importance as well as the dynamics of learning by doing and innovatively moving from comparative to competitive advantages (or from labor/resource- to capital- to idea/knowledge-intensive edge) along global value chains of production.

And insofar as the issue of the state vis-à-vis the market is concerned, the point is not to overplay on either side, and that the market and the rule of law ought to go side by side but both, being socially-embedded, need time to be nurtured and develop. A successful reform strategy is thus often a delicate act of multiple sequencing and balancing. When sequencing or balancing went awry, it would stifle growth, as the diverse experiences, successes and failures of many transitional economies have amply demonstrated.

Let me add a final point. In the past 40 years, just as China has learnt a great deal from other countries but didn’t copy them mechanically, we do not want other countries to copy us – or the China model were there any – mechanically. China has dynamically evolved and will continue to evolve arguably as the greatest transformation in human history. A key lesson from the Chinese experience is that, with clear vision and principled pragmatism, successful growth strategies also have to reflect diverse local conditions and be tailored to different stages of development. One size doesn’t fit all.

(Fu Jun is academic dean of the Institute of South-South Cooperation and Development at Peking University, and a member of the World Economic Forum’s Future Agenda Council on Economic Progress. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the view of CGTN.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3