Tech & Sci

09:49, 03-Jan-2018

US scientists grow hairy skin from mouse cells

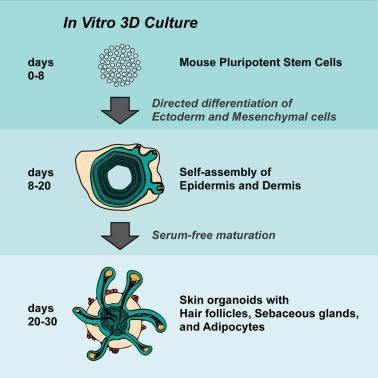

According to a study published on Tuesday in Cell Reports, American scientists used stem cells from mice to develop skin tissue with hairs.

The experiment helped improve the understanding of hair growth and created a new possibility for drug testing.

The study showed that a single skin organoid unit, developed in culture, can give rise to both the upper and lower layers of skin, and the two layers can grow together and allow hair follicles to develop. This allows hair to grow just as they would in the body of a mouse.

Karl Koehler, author of the paper and a researcher at the Indiana University School of Medicine, described the tissue like "a little ball of pocket lint that floats around in the culture medium."

"The skin develops as a spherical cyst, and then the hair follicles grow outward in all directions, like dandelion seeds," Koehler said.

Photo via Cell Press

Photo via Cell Press

Researchers said that the skin grew a variety of hair follicle types that were similar to those naturally present on the coat of a mouse. It consisted of three or four different types of dermal cells and four types of epidermal cells, creating a diverse combination that more closely mimics mouse skin than previously developed skin tissues.

They learned that the epidermis grew to take the rounded shape of a cyst, then the dermal cells wrapped themselves around these cysts. But when this process was disrupted, hair follicles never appeared.

"It's very important that the cells develop together at an early stage to properly form skin and hair follicles," Koehler said.

None of the previously cultured skin tissues were capable of hair growth.

The rounded shape of the tissue, however, prevented the hairs from shedding and regenerating as the hair follicles grew into the dermal cysts.

Koehler's team believed that once the hair follicles found a way to complete their natural cycle in the culture medium, the organoids could offer more possibilities for medicine and be used as a blueprint to generate human skin organoids.

"It could be potentially a superior model for testing drugs, or looking at things like the development of skin cancers," Koehler said.

Source(s): Xinhua News Agency

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3