Opinions

11:27, 09-Apr-2018

Opinion: A reality check on 'innovation mercantilism' in China

Guest commentary by Dr. John Gong

At the heart of the US Trade Representative’s Section 301 investigation report, there lies a caravan of accusations with regard to the Chinese government’s state aid in corporate China’s global expansion.

These accusations were first widely promulgated under the dubious name “innovation mercantilism” by an obscure think-tank outlet in Washington, DC, the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF), headed by Robert Atkinson.

Atkinson is trained neither as an economist nor a technologist, but he is fond of masquerading as an expert in innovation with such tenacious zealotry that one can only describe as a religion.

He has some really whacky ideas about pushing America’s STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) education, but this is a topic for another day. In any case, Robert Lighthizer’s Section 301 report sees Robert Atkinson’s fingerprints all over the place, and in some instances copied verbatim from his congressional testimony last year.

Robert Lighthizer, US trade representative, testifies during a Senate Finance Committee hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, US, March 22, 2018. /Bloomberg via Getty Images

Robert Lighthizer, US trade representative, testifies during a Senate Finance Committee hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, US, March 22, 2018. /Bloomberg via Getty Images

But both Roberts’ reports are long in accusations but short on evidence and relevance.

Let’s start with the so-called forced technology transfer in exchange of market access in China. Lighthizer’s laundry list of such instances, many of which are dated at least two decades ago, gives the impression that corporate China’s ascent in innovation is the result of corporate America’s technology transfer.

But nothing can be further from the truth of that narrative. As a matter of fact, technology transfer in exchange for market access is a proven recipe for failure for innovation in China.

Most of China’s national champions successfully competing on global markets have grown to prominence with indigenous technology development. Venerable names like Huawei, Haier, and Sany Heavy Industries are invariably noted for their indigenous R&D prowess.

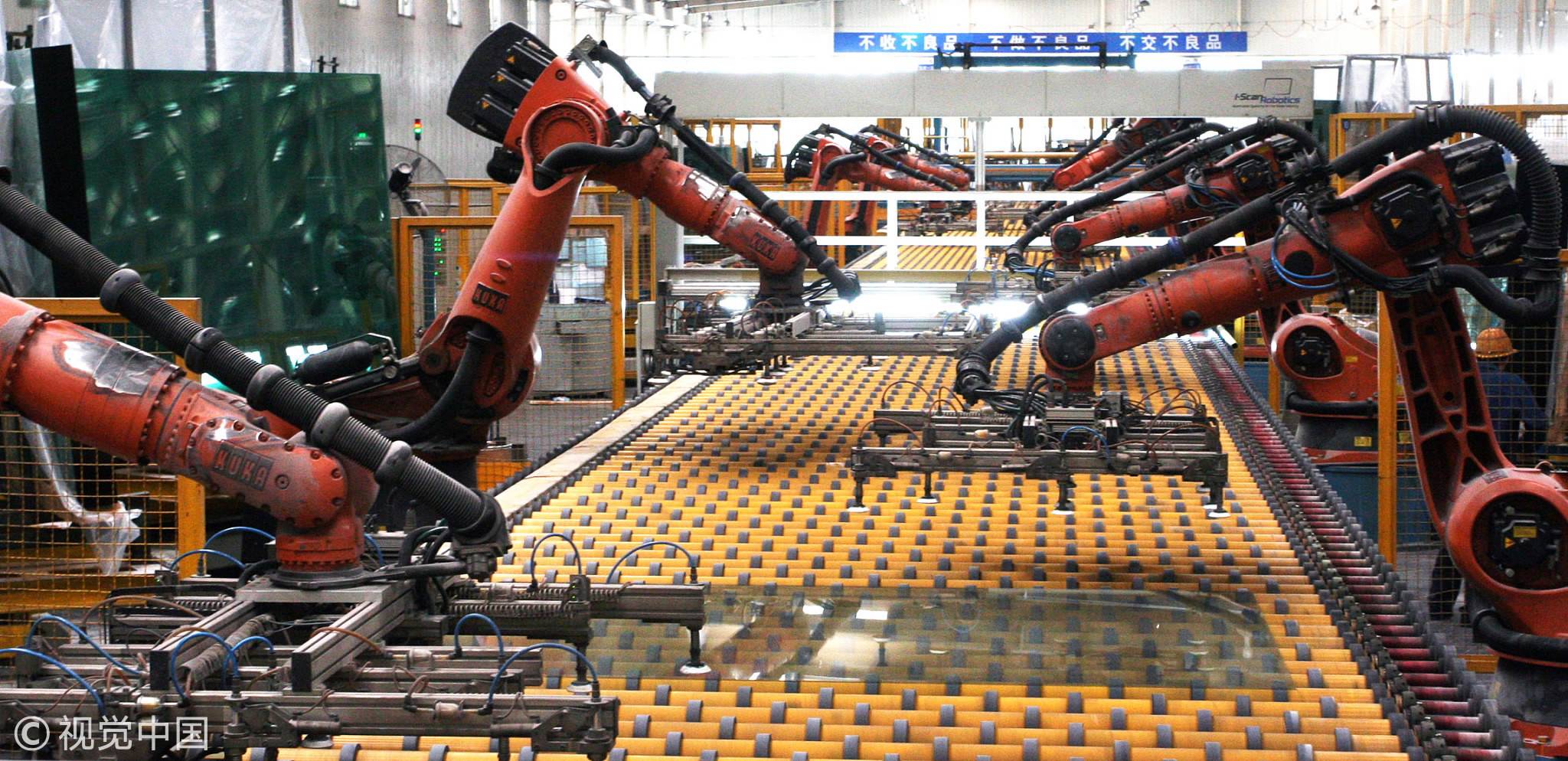

Heavy machinery is seen at Sany Heavy Industry assembly plant in Lingang Industrial Park, near Shanghai, June 28, 2012. /VCG Photo

Heavy machinery is seen at Sany Heavy Industry assembly plant in Lingang Industrial Park, near Shanghai, June 28, 2012. /VCG Photo

Sany Heavy Industry is a good example compared to Caterpillar’s joint venture in Xuzhou, which is nowhere close to Sany’s worldwide success. While I was running the China research center (on a part time basis) for a major American management consulting company two years ago, I interviewed Sany’s CTO Yi Xiaogang.

He told me that any company that is built on foreign technology transfer has a defective innovation gene from the very beginning, and is destined to be mediocre in ensuing years. “We, at Sany Heavy Industries, are indigenous from day one, and we never have the habit of following others,” he resoundingly assured me at that time.

Another example can be found in China’s automobile industry, which is noted for the joint ventures and technology transfers.

The success examples in this industry, such as Geely and Great Wall Automobiles, are precisely those private companies that didn’t go through the joint venture process, nor have they seen any technology transfers whatsoever. Those SOEs who do however, are struggling to keep up.

Geely is now fast-paced to record over two million units of sales this year, which will probably place it close to the world’s top 10 largest automakers. Great Wall Automobiles, which is becoming China’s version of Jeep, has been averaging over 40% growth over the years, and is also the most profitable automaker in China.

An assembly line of Geely automobiles is seen at the Belarusian-Chinese closed joint-stock company BelGee plant in Zhodino, Belarus, November 18, 2017. /VCG Photo

An assembly line of Geely automobiles is seen at the Belarusian-Chinese closed joint-stock company BelGee plant in Zhodino, Belarus, November 18, 2017. /VCG Photo

Lighthizer’s report goes through great length about China’s industrial policy and state subsidies. As much as I dispute its scale and intensity in many industrial sectors in China, I wish this stuff to be gone too as Lighthizer wishes, but for a different reason – it doesn’t work, its impact is limited and therefore doesn’t even qualify as a meaningful reason in explaining many of the successful innovation stories in China.

That government subsidy to corporate R&D is not productive nor effective, crowding out private investment, has wide empirical evidence in the relevant innovation literature covering many countries, and China is no exception, e.g., in a recent paper by Philipp Boeing published in an authoritative academic journal, Research Policy.

When I was running the China research center for that American management consulting company, I organized a study regarding corporate China’s R&D activities. I used several large databases to identify the best companies in China in terms of being high performers based on a data envelopment analysis (DEA) as well as delivering top innovation results compared to its peer group.

I even came up with a name for this type of companies, what I call top dogs in the canine innovation theory. What I found is that over 50% of those companies belonging to this top dog category are never enamored with government industrial policies, and in fact they deliberately stay away from activities vying for government grants and subsidies.

Fuyao Auto Glass is a case in point, which is my favorite company in that study. As the name indicates, it manufactures auto glass for all the major automakers worldwide, and in China, occupying over 70% market share. The company has also opened a 600-million-dollar factory in Dayton, Ohio, creating nearly 3,000 jobs in the local community.

A production line of Fuyao Auto Glass in Fuqing, Fujian Province, April 2, 2009 /VCG Photo

A production line of Fuyao Auto Glass in Fuqing, Fujian Province, April 2, 2009 /VCG Photo

Now this is the American heartland, the center of the rustbelt, and the state where Donald Trump famously claims that the China trade has closed down factories and destroyed jobs.

During a one-on-one interview with the company’s CTO Bai Zhaohua, he said, “We stay away from government R&D programs; they don’t help us much and they are distractions. We are not short of money to fund our own R&D.”

In short, even if some of the things mentioned in the Section 301 report may be facts, they are outdated by decades not reflecting the fast-changing market dynamics in China, and more importantly, are mostly irrelevant anyway in explaining corporate China’s success in innovation.

Making blind accusations without researching into the real stories of innovation in China appears to be condescension, arrogance and outright hubris on the part of the Trump administration. And waging a trade war is not going to achieve his policy objectives, either in reducing the trade deficit or rolling back corporate China’s torrential wave of new patents next year.

My email address is available online. Upon request, I would be happy to email the White House a copy of my two-year-old innovation study, which is still much more updated than most of the content in the Lighthizer report.

(Dr. John Gong is a research fellow at Charhar Institute and professor at the University of International Business and Economics. The author’s opinions are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of CGTN.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3