Politics

17:20, 06-Feb-2018

The story of FGM: ‘Only a cut woman is a good woman’

By Zhao Li

“Only a cut woman is a good woman,” Waris Dirie said.

“This is the way she stays a virgin,” Dirie kept going. “Until her wedding night. And her man opens her.”

These lines are from the 2009 film “Desert Flower,” which is based on the autobiography of the same name of the Somalia-born supermodel. Like almost all girls in her community, the model-turned human rights activist had undergone female genital mutilation (FGM) when she was a little girl.

Portrait of supermodel Waris Dirie of Somalia. / United Nations Photo

Portrait of supermodel Waris Dirie of Somalia. / United Nations Photo

What cut? Cut what?

“Cutting,” “female circumcision” or “female genital mutilation” as it is more commonly known, “involves altering or injuring the female genitalia for non-medical reasons,” according to the United Nations. It is usually carried out on young girls between infancy and age 15.

Based on UN data, over 200 million girls and women –equivalent of the total population of both the UK and France – alive today have been cut in 30 countries primarily in Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

Approximately 6,000 girls undergo the procedure every single day, per the book “The Locust Effect,” coauthored by founder and president of International Justice Mission Gary Haugen and a US federal prosecutor Victor Boutros.

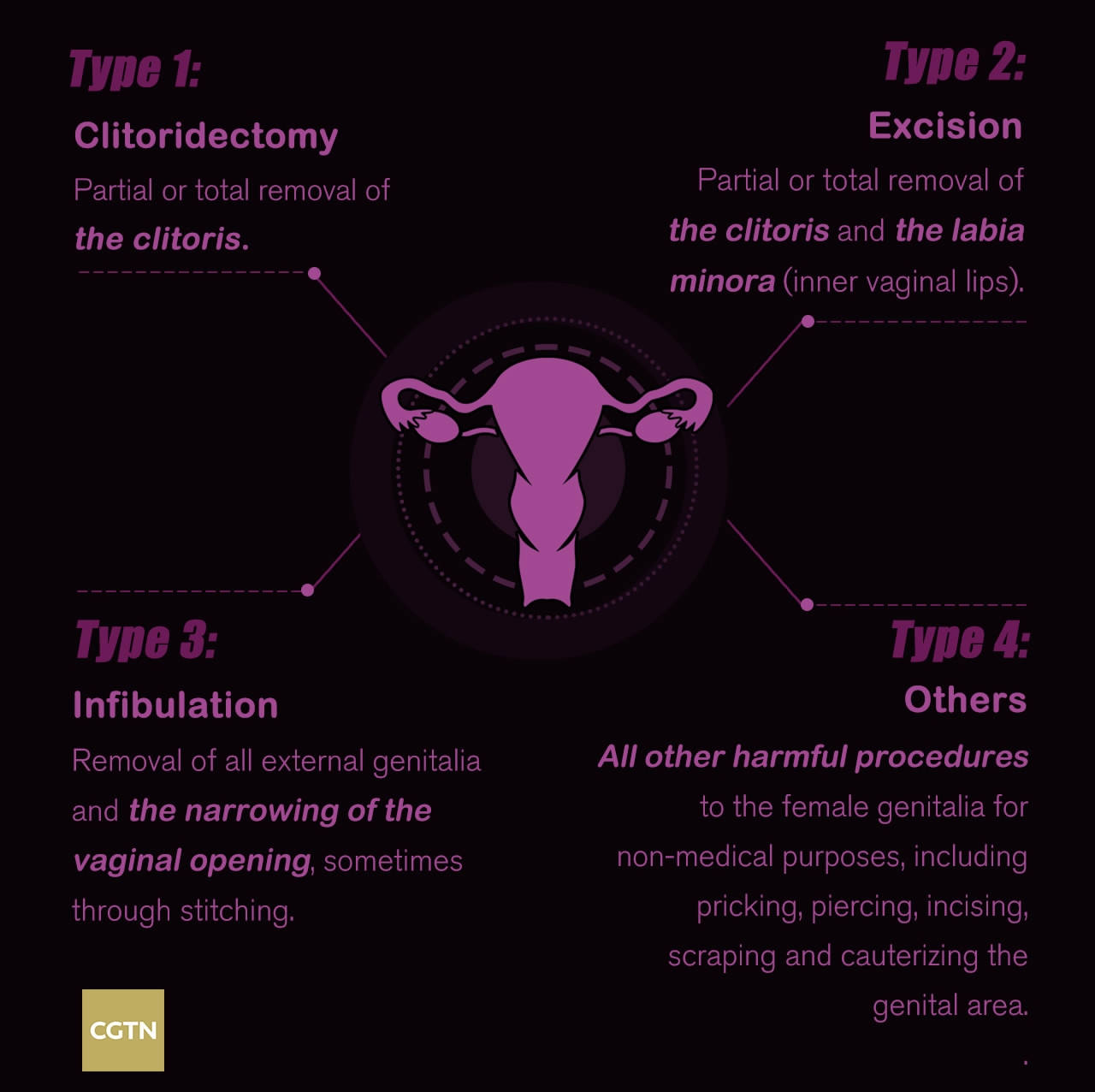

The World Health Organization (WHO) has classified FGM into four major types as follows:.

Why cut?

The reasons as to why FGM is practiced vary from region to region. The most commonly known ones, cited by the United Nations and Al-Jazeera, are listed below:

Does FGM have health benefits?

FGM has no health benefits, the WHO says. It damages “healthy and normal female genital tissue and interferes with the natural functions of girls’ and women’s bodies.”

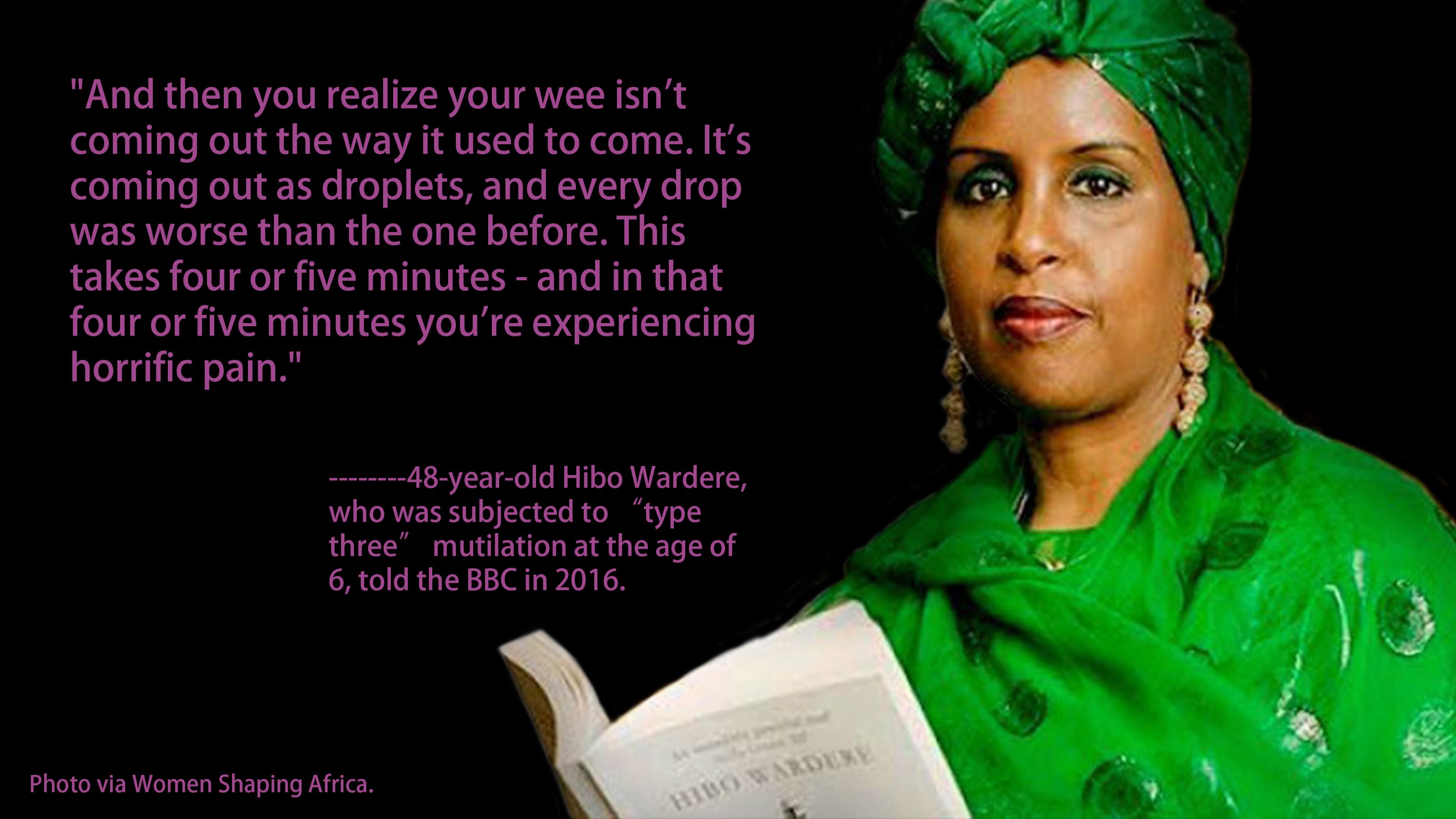

As the WHO reports, immediate complications can include severe pain, excessive bleeding which may lead to death, infections, urinary problems and many others. Long-term problems can include urinary, menstrual and sexual problems, childbirth complications due to the matchstick-sized hole – as Hibo Wardere told the BBC – the practice leaves on girls.

The severity of damage can depend on the type of FGM performed, and, as Al Jazeera discovered, also on whether the “cutter” had medical training and used sterile tools.

Cutter Anna-Moora Ndege shows the razor blade she used to cut girls' genitals , on June 25, 2015, in Mombasa, Kenya. /VCG Photo

Cutter Anna-Moora Ndege shows the razor blade she used to cut girls' genitals , on June 25, 2015, in Mombasa, Kenya. /VCG Photo

The practice is usually carried out by "older members of the community, often women who lack proper medical training,” according to the media network.

There is also psychological harm to the recipients.

“[The girls] feel that it’s a humiliation for them to go through such a practice,” said Mona Amin, a UN Development Programme FGM expert in Egypt told the UN.

“Young girls are very touched when we talk to them about FGM because the most common word that we hear from women is that it’s the worst day of my life.”

What has the international society done?

The practice is “recognized internationally as a violation of the human rights of girls and women,” the UN has written on its website.

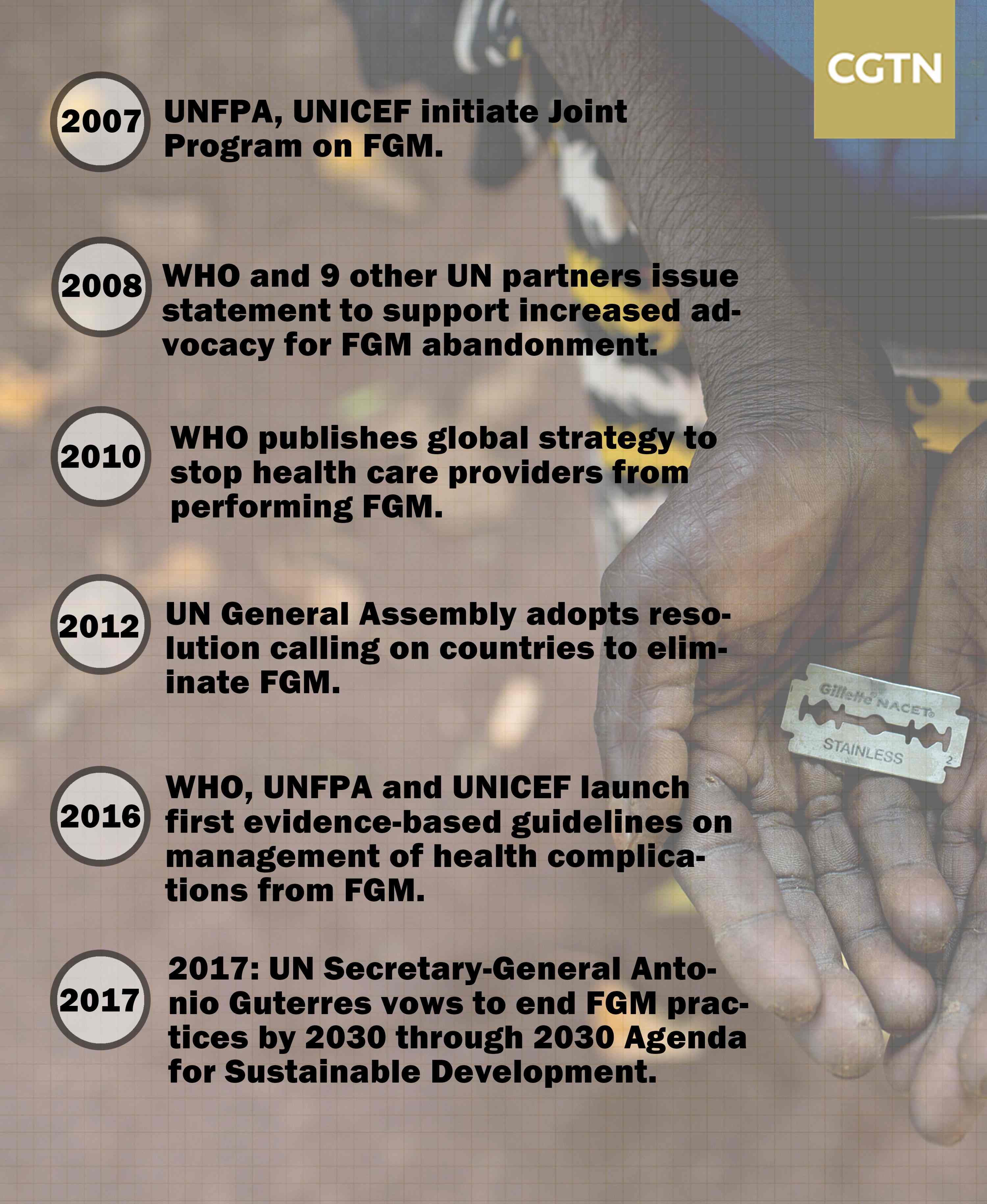

According to data released by United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), FGM has been banned by most African countries as well as European and Western nations.

Penalties range from a minimum of six months to a maximum of life in prison. Some countries also include fines.

WHO has partnered up with other UN agencies UNFPA and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in fighting against FGM.

As Dirie said at the end of the movie, “Whatever happens to the least of us has an effect on all of us.” On this day of International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation, we are here calling for an end to FGM.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3