Tech & Sci

08:06, 06-Oct-2017

Facial recognition: Final frontier of the privacy battlefield

CGTN

Apple's iPhoneX has brought the facial recognition technology back to the spotlight of public interest. Its ability to read human faces with high accuracy enabled by advanced algorithm is quite impressive. But some people are also concerned over potential risks of privacy infringements as it becomes widely used.

In Britain, a facial recognition system is designed to replace the need for tickets on trains; in Germany, for police to discover terror suspects recorded by CCTV cameras. In China, it verifies the identities of ride-hailing drivers and permits customers to pay with a face scan. However convenient it may be, privacy campaigners consider it as highly dangerous in the digital age where we are living and may change the traditional definition of privacy. Why is that?

A fast-pass lane equipped with facial recognition system being developed by the Bristol Robotics Laboratory in the UK. / CFP Photo

A fast-pass lane equipped with facial recognition system being developed by the Bristol Robotics Laboratory in the UK. / CFP Photo

As faces are considered as public information, an algorithm which encodes and analyzes those images does not seem to intrude on privacy at first sight. However, things change when a bigger database is accessed to match the calculating result with the attempt to expose more information such as people’s identity.

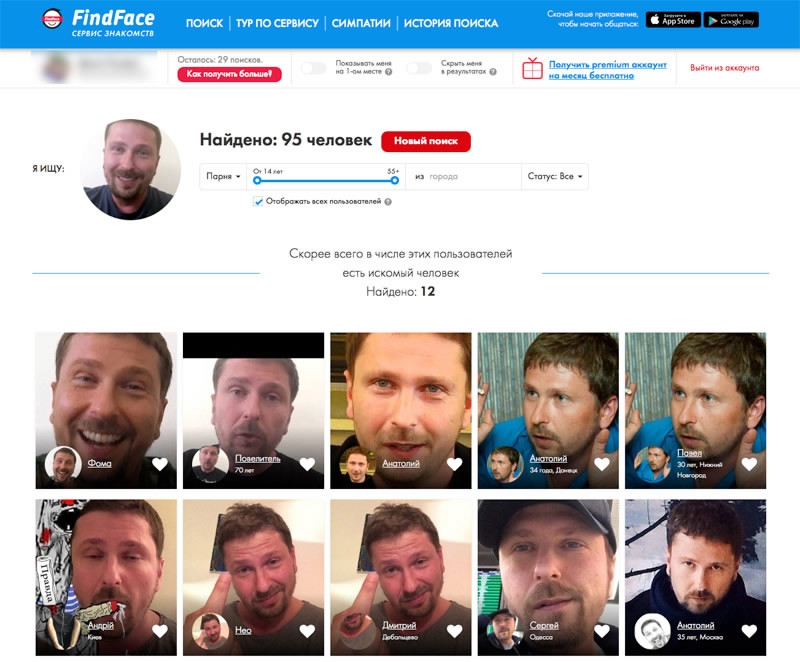

FindFace, an app in Russia, compares snaps of strangers with pictures on a Russian social network and identifies people with a 70% accuracy rate. There algorithm allows to search through a billion photographs in less than a second from a normal computer. Then the app will give you the most likely match to the face uploaded. We’ve already seen what can go wrong with it: criminals have used it to scan the web and identify women who had appeared in adult films and then blackmail them.

A display of match result given by "FindFace" /Screenshot of Web Page

A display of match result given by "FindFace" /Screenshot of Web Page

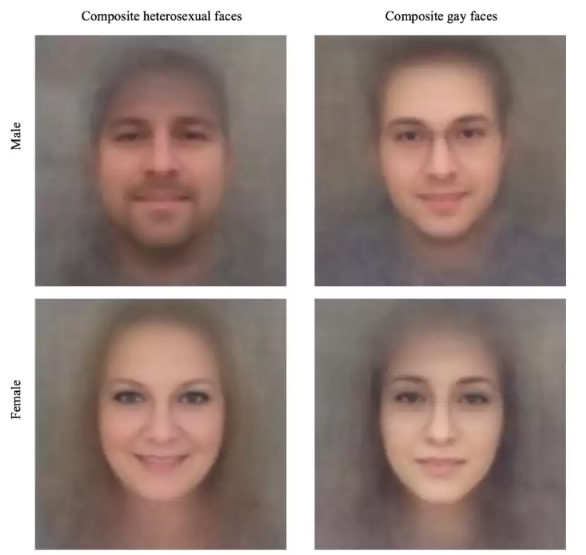

Another experiment conducted at Stanford University has demonstrated that an algorithm trained by photos collected from dating websites can easily distinguish a gay man from a straight man, with much higher accuracy than humans. That could prove to be an alarming prospect in countries where homosexuality is a crime.

Large companies such as Apple and Facebook have always pledged to protect customer privacy. However, it is justifiable to remain skeptical upon those promises considering their obsession with gathering as much data as possible about users. Even if the data were preserved to themselves, it could be processed by hackers who may break into the device or the data from where content is stored; or internal employees of the company who improperly misappropriate customer content; or the police, by means of a subpoena or search warrant.

Composite images of gay and straight subjects according to the Stanford experiment conducted by researchers Michal Kosinski, Yilun Wang / Images by Michal Kosinski, Yilun Wang

Composite images of gay and straight subjects according to the Stanford experiment conducted by researchers Michal Kosinski, Yilun Wang / Images by Michal Kosinski, Yilun Wang

In Europe, regulators have embedded a set of principles in forthcoming data-protection regulation, decreeing that biometric information including face-print belongs to its owner and that its use requires consent. In the US, however, tech giants are reluctant to support similar legislative attempts, insisting that getting that sort of consent isn’t feasible.

At the current stage, facial recognition technology may not be that powerful to put a name to any face snapped in public. However, it is only a matter of time. We can do our best to head off this worrisome perspective, but for those who just can’t resist posting endless selfies online, it's something to really think about.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3