Business

21:39, 01-Dec-2017

Highlights of Janet Yellen’s achievements at the helm of the Fed

CGTN

Chair of the US Federal Reserve, Janet Yellen, is entering the final stretch of a four-year tenure which was a clear success measured by the Fed’s dual mandate of promoting maximum employment and stable prices.

Here's a review of the mixed economic legacy Yellen leaves behind:

Low unemployment and inflation

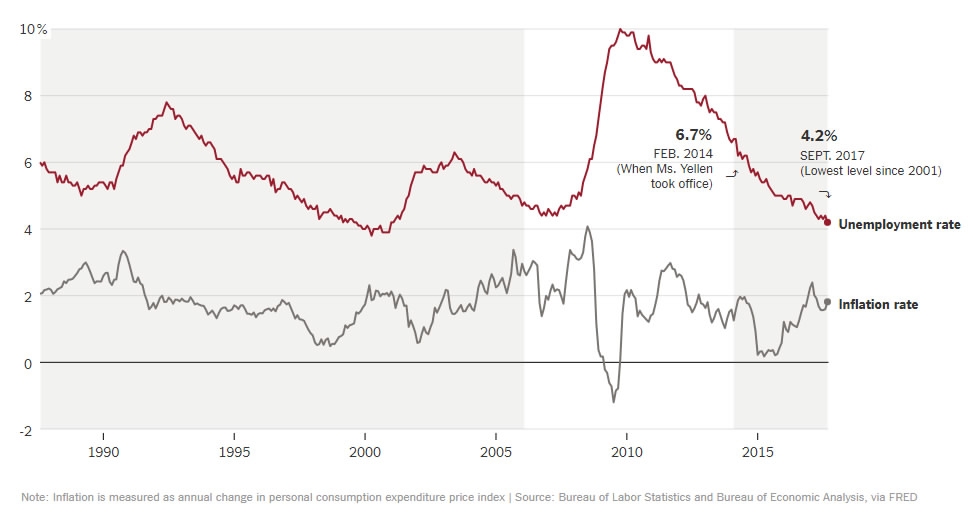

Unemployment is at its lowest level since 2001 on her watch, and the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation has generally stayed well below its 2 percent target.

The Federal Reserve, led first by Ben Bernanke and then by Janet Yellen, took “traditional” and “nontraditional” policy actions over the past decade to spur a faster and full recovery from the Great Recession.

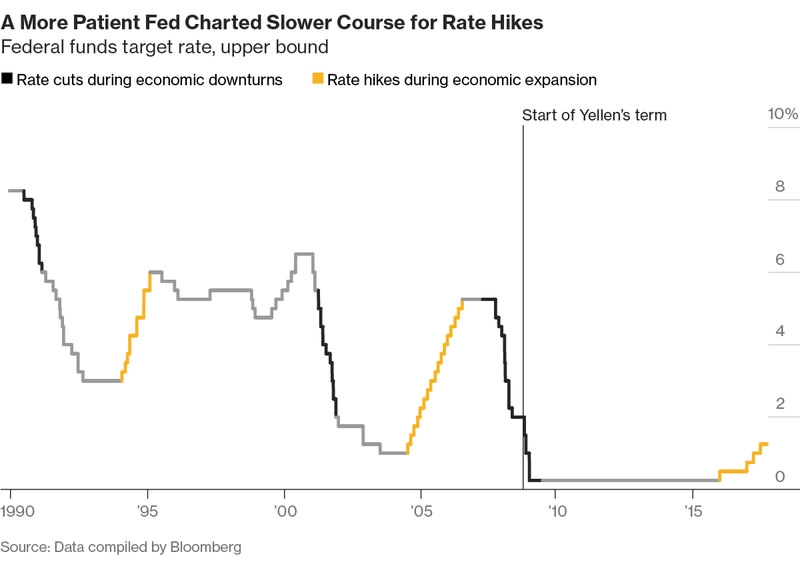

During and after the onset of the Great Recession, the Federal Reserve slashed the federal funds rate to zero and essentially kept it there (traditional policy action); it also launched credit easing programs and large-scale asset purchase (LSAP) (nontraditional).

Yellen, known for her jobs-first approach, deserves credit for continuing the Fed’s support for recovery past 2013 when critics became particularly loud, claiming that it was time for the Fed to prioritize keeping inflation low rather than making further progress toward full employment.

To be sure, inflation hawks were criticizing the Fed between 2009 and 2013, but it was easier to ignore them when the headline unemployment rate still exceeded 7 percent – far above what any reasonable analyst could call full employment.

When Yellen became chairwoman in February 2014, the Fed had held interest rates near zero for more than five years in an effort to revive the economy. With unemployment falling and inflation edging upward, she came under almost immediate pressure to raise rates. Instead, she waited nearly two years – until December 2015 – to do so, then another full year before doing so again.

The Fed has now approved four quarter-point rate increases under Yellen, and is widely expected to raise rates again in December.

Yellen has insisted on pursuing her policy of gradual monetary tightening as she banks on the tightening labor market eventually pushing inflation higher.

It has been five years since the Fed hit its preferred measure of this target, but it is this year’s shortfalls that have left officials mystified.

In fact, one of the most serious criticisms of her tenure may be that inflation has failed to rise as expected, and remains well below the Fed’s two percent target.

An incomplete job market recovery

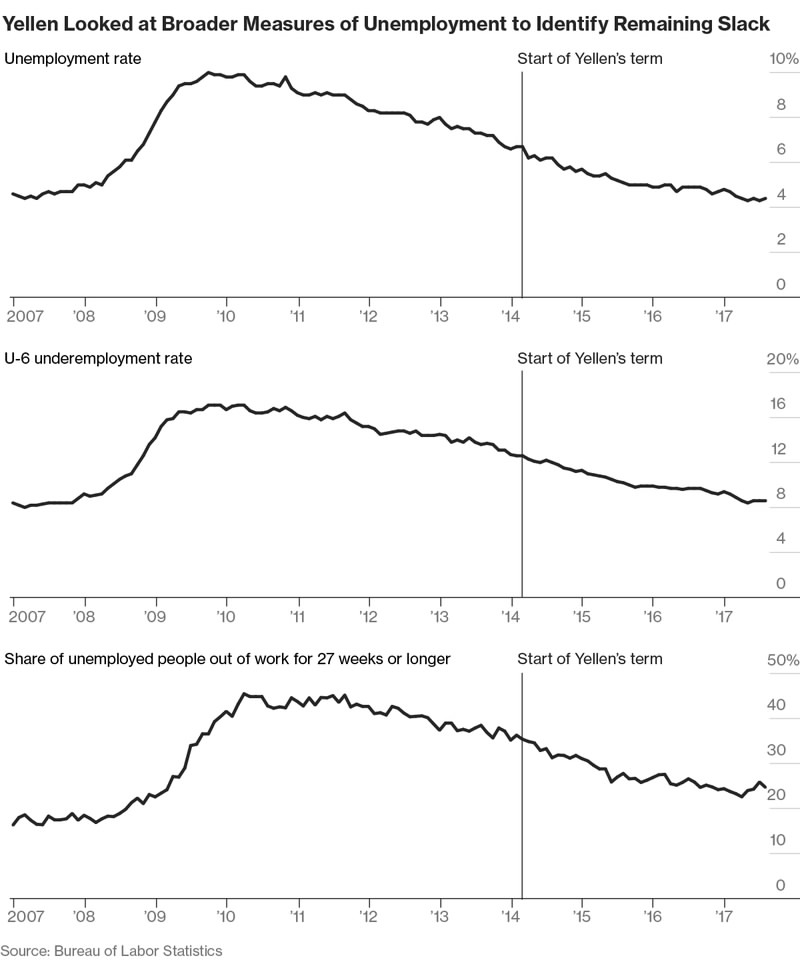

Shortly after taking office, Yellen indicated that broader measures of labor market slack needed to be examined to appreciate the enduring damage left by the Great Recession, and the central bank’s job of helping the economy heal from the recession wasn’t done until wages for regular workers began to rise in earnest.

While the pre-crisis Fed was of the belief that the unemployment rate served as an excellent proxy for labor market activity, Yellen was the one who said “just because the unemployment rate is falling doesn’t mean there still aren’t a lot of people who were pushed outside of the labor market.”

The official unemployment rate used by the US government and conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is called the U-3 rate.

An alternative gauge of labor market slack is called U-6 rate, which includes discouraged workers who have quit looking for a job and part-time workers looking for full-time employment. The U-6 rate is considered by many economists to be the most revealing factor of a country’s unemployment situation since it covers the percentage of the labor force that is unemployed, underemployed, and discouraged.

The U-6 rate has returned to its pre-recession levels under Yellen, but wage growth has, like inflation, been surprisingly weak, pointing to an incomplete job market recovery.

Balance sheet reduction

By the time Yellen took over as Fed chief, the emergency-era bond purchases, also known as “quantitative easing," has left her with a challenge: How to unwind a 4.5-trillion-dollar balance sheet without repeating the market roiling taper tantrum of predecessor Bernanke.

For most of her tenure, the Fed bought new bonds to replace ones that were maturing, keeping its total holding essentially flat.

But in September, the Fed said it would begin gradually paring its holdings by allowing some bonds to roll off its balance sheet.

Jerome H. Powell, Yellen’s nominated successor, will continue the work, and he expected to see the balance sheet shrinking to between 2.5 trillion dollars and 3 trillion dollars.

Powell acknowledged the benign inheritance he will enjoy when he appeared before the Senate, describing output as strong and predicting growth of as much as 2.5 percent this year and next. Yet the recovery remains a partial one, and as Powell implied, many of the lingering problems the US faces may prove beyond the central bank’s powers to fix.

11160km

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3